Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The Toledan night is an expression that is built up orally over the centuries, using an assumed historical fact with obvious shades of legend. The origin of its meaning can be found in the day of the moat, which occurred in 797, which it was first documented eight centuries later. According to tradition, during the Emirate of Cordoba, when Toledo enjoyed a certain autonomy, an expedition was sent from the south to end this independence. For this reason, a palace was built with a moat, the most influential people in the area were invited (up to 400, according to some chronicles), and after being beheaded they were thrown into the enormous hole. This narrative is established as a witness to the mythological nature of the city.

The visits of Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí and Federico García Lorca to Toledo have fed the mythological imagination of the city. Today we know that the group was much more extensive and that they made Toledo an avant-garde setting, a dark place where religious fervour was admired as a surreal practice. However, for a long time, the only reading of these events has been through the story based on the surnames of these three omnipresent figures.

The young Buñuel was fascinated by the mysterious air that Toledo gave off in the 1920s. On his second trip, while drunk in the cathedral cloister, he had a vision. Thus, thanks to a miracle like so many other saints, he decided to found his own congregation: The Order of Toledo. As he had done throughout his career, the director made use of his Catholic education to build an ideology in which it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between apology and sarcasm.

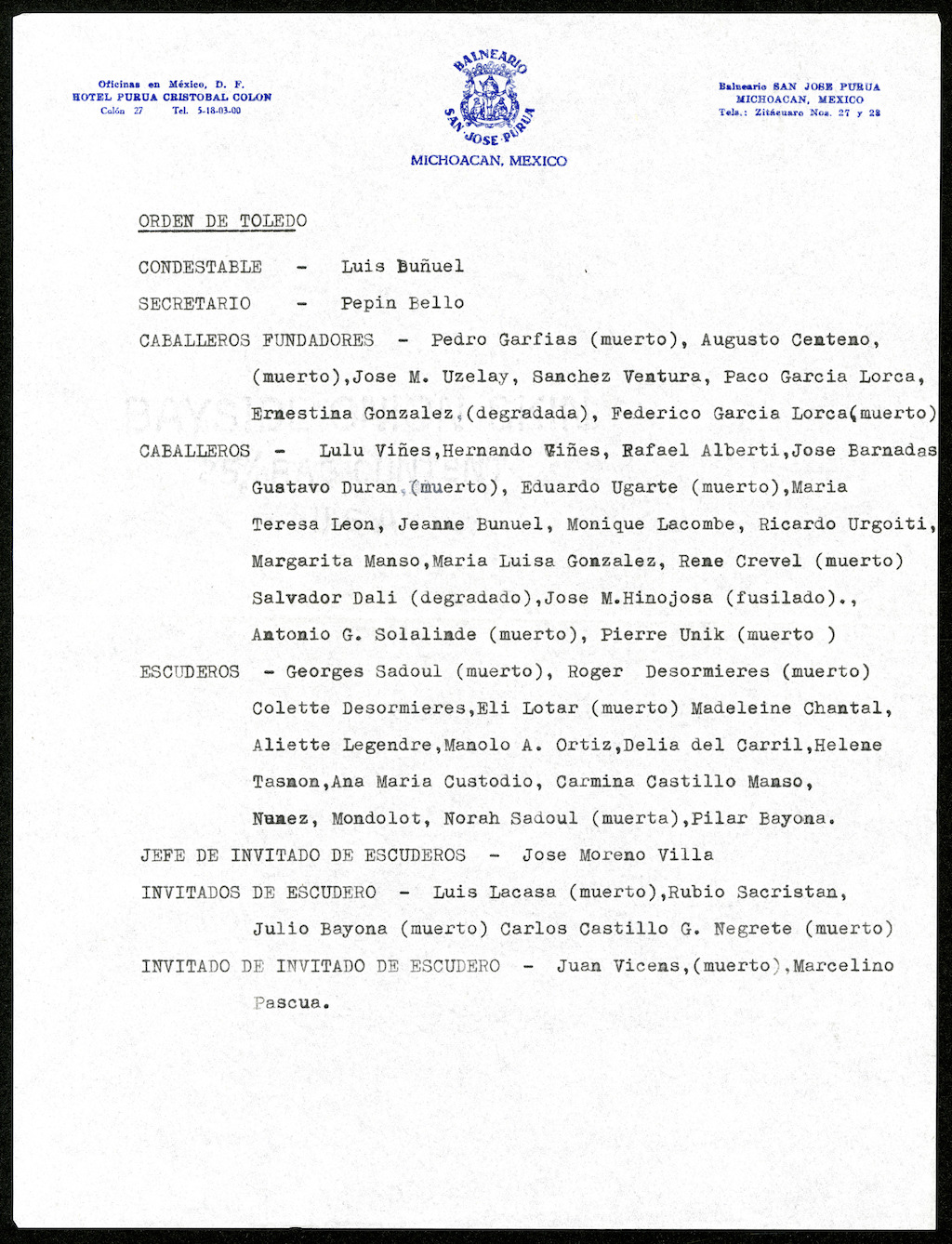

From 1923 to 1936, Buñuel became the promoter of excursions from Madrid in search of delirious episodes stimulated by the consumption of Yepes wine. The group developed a terminology for their crusades based on military and religious organizations. Buñuel proclaimed himself “condestable” and differentiated between the founding knights such as the brothers and poets Federico and Francisco García Lorca, present at the inaugural visit, and those who joined later such as María Teresa León or Rafael Alberti. To obtain the title of knight, it was necessary to stay awake all night, and those who preferred to sleep were relegated to being squires, or even guests, like the rationalist architect Luis Lacasa.

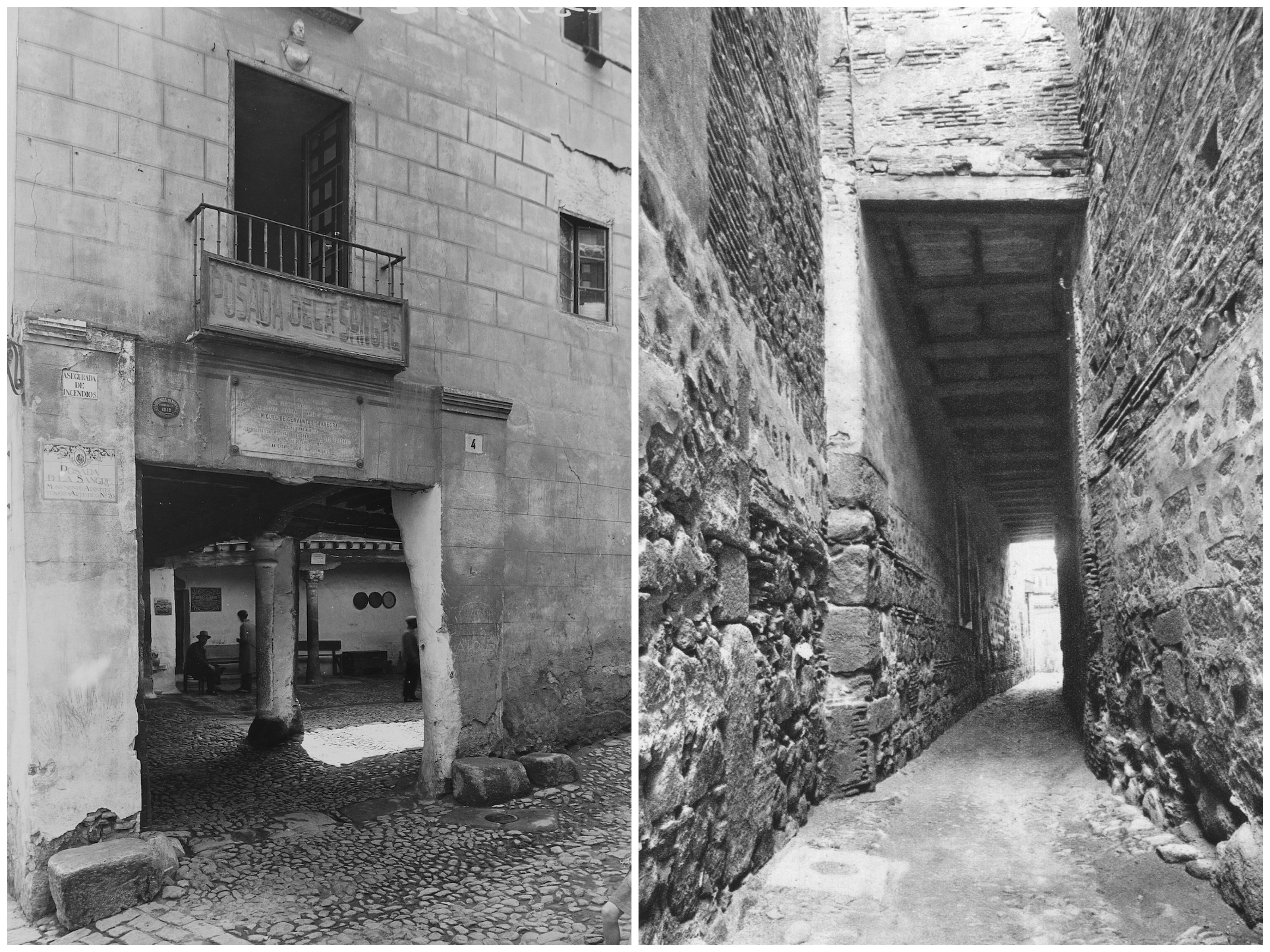

From the outset, certain precepts were imposed that were repeated in the form of a ritual: they would stay at the Posada de la Sangre, eat at the Venta de Aires and visit the tomb of Cardinal Tavera, Berruguete’s last work, made from the archbishop’s death mask. During those visits they recited poems, subverted the order by disguising themselves as clergymen or beggars and went to places such as the Plaza de Santo Domingo el Real to listen to the nightly prayers of the nuns. However, one of their first stories takes place in the light of day, when a blind man takes some members of the Order to his home. There, the group discovers that it is a family of blind people and that there are no lamps or candles in the rooms. In addition, they find numerous paintings made with hair hanging on the walls. In them, hair cemeteries with their tombs and cypresses also created from hair.

Despite the fact that contemporary history has tried to categorically differentiate between the real and the imaginary and, on most occasions, to eliminate the latter, Buñuel uses his memories as an opportunity to rescue his youthful adventures as a form of self-fiction. In Mi último suspiro (1982), the director devotes a chapter to the Order of Toledo and details how it works, as well as reviewing his most surreal anecdotes, such as having hypnotised a prostitute with whom he never had sex during his first night in Toledo. Although the director has been criticised for the inaccuracy of his versions, it is clear that this disciple of the subconscious finds greater veracity in the constructed memory than in the facts themselves, allowing himself the luxury of providing clues and details through occultism.

The critical essence against the Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and the ridicule of the ecclesiastical institution are fundamental parts of the group’s approach. The Order of Toledo is presented as an opportunity to decentralize the vision of the avant-garde and enrich the mosaic of collaborations and influences that it represented. Among its almost fifty members, there are personalities who have remained in the shadows, such as the multifaceted Moreno Villa, whose culture influenced the work of the Residencia de Estudiantes generation. Delia del Carril is another great example because she was erased from history despite having corrected for years the poetry books of her second husband, Pablo Neruda, and influenced the sophistication of his style.

During the 1930s, after his stay in Paris, Buñuel continued to act as a cicerone with visitors from the French avant-garde. This is how René Crevel, the overflowing surrealist writer who had to hide his bisexuality from the opposition of the Bretons, arrived in Toledo. The constable also comes repeatedly with the composer Gustavo Durán, with whom he shares the communist ideology and whom he has related to Lorca. Duran had an atypical life for his time and before marrying and forming a family, he had an eleven-year love affair with the Canarian painter Nestor, whose work obsessed and influenced Dalí. The war finds Duran in Madrid working as a film dubber, he then joins the Republican side, and after working as a spy in several countries, he spends the last years of his life in Greece, where he is visited by Gil de Biedma.

During the last years of the Order of Toledo, one of the most assiduous will be Eduardo Ugarte, co-director of the university theatre group La Barraca. With him, Buñuel worked on different scripts, but in addition to his drunkenness, the Aragonese remembers a psychophony that the two witnessed in the alleys of Toledo. Without fear of being branded a fantasist, the director recounts in his memoirs how the two heard a group of children reciting the multiplication tables from memory inside a room that turned out to be empty.

The outbreak of the war meant the end of the Order of Toledo and the loss of most of the material evidence, with it the titles of the knights and the mural that Dalí painted in the Venta de Aires disappeared. However, the lists drawn up by Buñuel and the mentions made by María Teresa León, Alberti and Moreno Villa in their respective memoirs show the feedback that took place between the Generation of 27, Surrealism and the Sinsombrero. The Order recovers numerous truncated biographies and shows the essence of the Spanish avant-garde, which was particularly rooted in the land and history. Recovering the group’s practices is an alternative reading that was censured by Franquism and later questioned for its subjectivity and esoteric essence. Perhaps the time has come to use the privilege of the great names to resignify the Toledo night from the myth and enrich it with the critical legacy of a more inclusive discourse.

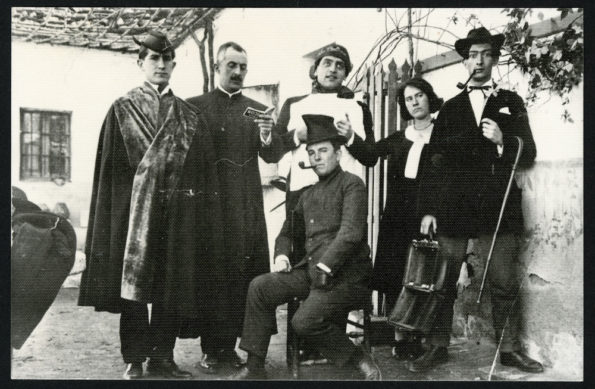

(Front image, from left to right: Pepín Bello, Moreno Villa, Luis Buñuel, Ernestina González, Salvador Dalí and José María Hinojosa (sitting) in the Venta de Aires, 1924)

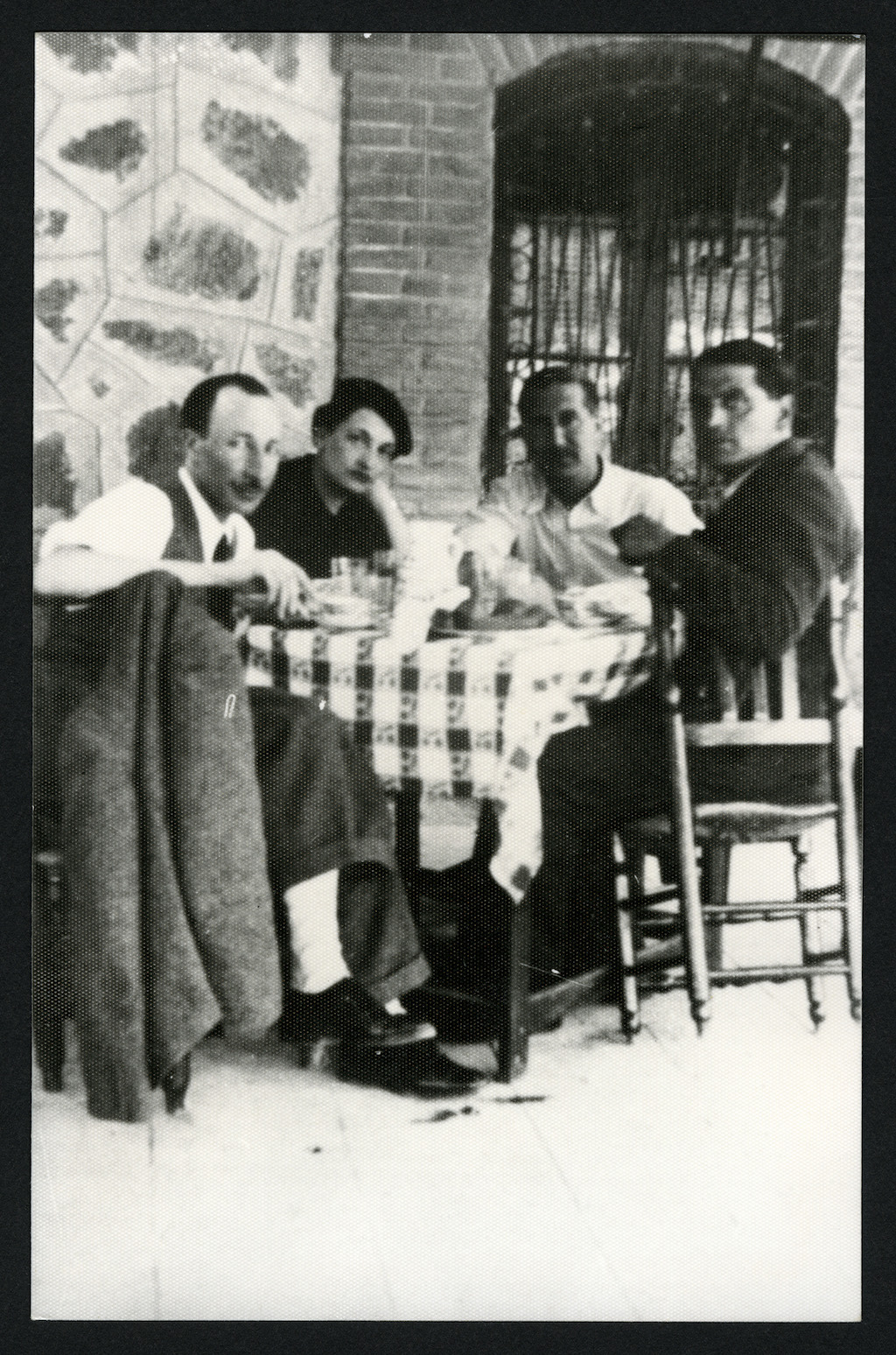

Left to right: Hernando Viñes, Lulú Jourdain, Pepín Bello y Luis Buñuel in Toledo, 1936

List of member from The Order of Toledo typed by Buñuel

Left: Posada de la Sangre façade in 1920. Right: Cobertizo de Santo Domingo el Real

Cardenal Tavera’s sepulchre, ca. 1920

Roberto Majano was born in a walled city of medieval essence the year the USSR was dissolved. An art historian and cultural manager, his career has developed in the fields of communication, education and public relations. With a rural childhood and a nomadic life, his experience is divided between Spain and Italy, where he has curated several contemporary art exhibitions and collaborated with different institutions in the development of cultural events.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)