Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

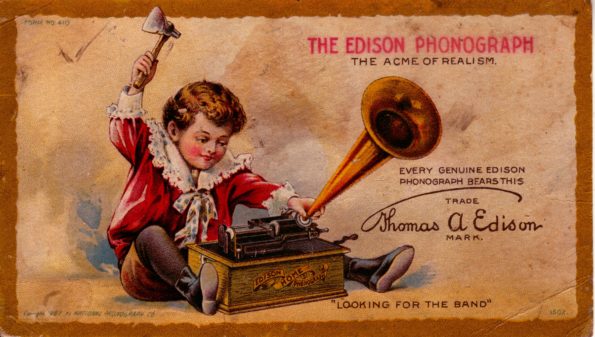

Imagine any city as a large wax cylinder similar to the one contained in the phonograph that Thomas Alva Edison patented on December 24, 1877. The different voices that inhabit the global city could be registered in that cylinder, but the selection criteria prior to that registration would undoubtedly leave many voices silenced. When years later Edison perfected the phonograph, he presented it at the Universal Exhibition in Paris (1889), where it would become one of the greatest attractions. To prepare the event, a few months before, he sends his collaborator Adalbert Theodor Edward Wangemann to Europe, who, on October 7, 1889, records the voice of the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Encouraged by the possibilities of the invention, the German politician launches to speak in English, Latin, German and dares to intone the beginning of The Marseillaise, before ending with a little morale for his children[1]. That the winner of the Franco-Prussian war sings the “Allons enfants de la patrie…” in good French is at least ironic, but it cannot be denied that the inventory it displays is a warning that, if the technical element supports it, any sound event can be recorded, regardless of its relevance.

Shortly before, on December 23, 1888, Vincent van Gogh cut his left ear with a razor at his home in Arles. Tradition explains that he wraps it in newspaper and takes it to a prostitute named Rachel. Although Rachel was Gabrielle and instead of a prostitute, she was in charge of cleaning the brothel, the painter’s gesture does not cease to be surprising.

Bismarck’s voice singing the French national anthem and Van Gogh’s gift ear in a brothel could well serve as a prelude to the majority sounds that the large wax cylinder of the global city has recorded ever since. It will be said that the music that the city intones are multiple and that they generate different routes, however, in many of them a fundamental tone is recognized that responds to a type of symphony, to a joint singing that corresponds to an economic system and of thought that fixes the height from which it is necessary to inhabit also from the ear.

If the city were that great cylinder of wax still today, and if we had certainly understood that the world is listened to and not only looked at, then placing listening as the centre would have meant displacing the way of inhabiting the world and of inhabiting oneself.

To inhabit the world from the ears means to attend to the polyphony of its places; to learn to listen to the melodies that compose it. In that big wax cylinder that cities can be, the neoliberal melodies that lead them are registered in a sonorous becoming that does not take into account all the voices. From the listening point of view, it is therefore necessary to ask ourselves about the city that sings in us and about the city that we let sing. From listening, it is necessary to remember Van Gogh’s gesture and to ask what it has meant, for listening itself, the attention to the ubiquity of sound in the city.

To listen is to activate a device that can contribute to propagate or stop the neoliberal melodies that, mostly, forge certain forms of life. This device once revolved around the model of attention and distraction. To stop these melodies, it was said that it was necessary to exercise critical listening, to discipline listening. The possibility of propagation of these melodies was given instead by the maintenance of a distracted listening. In today’s control societies, everything has become a little more confusing. The ubiquity of the sonorous requests the ear incessantly, and distraction has become a measure of protection. Listening practices are debated between the incessant recycling of sounds that pass from everyday life to the still world of art, and the evocation of Mangon, the sound sweeper who, with his sonovac, sweeps away the sounds of the city in James Graham Ballard’s story[2].

After more than a hundred years of listening to the sounds of the world, we forget to listen to their silences. We also forget to make silence in our own listening: to lend ears, to give away our ears, as in Van Gogh’s excessive gesture.

Paying attention to the ears one hears the tension generated by the melodies imposed by the economic way of inhabiting the global city. These melodies were prefigured in the uses that the inventor of the phonograph had devised for his invention. Among them, clocks that could announce with an articulated voice the time to go home or to go to eat. The same clocks that now count our steps and admonish us when we do not comply with the planned program.

Consequently, paying attention to the global city means paying attention to its silences, as did the sound artist Susan Philipsz with her proposal Surround Me: A Song Cycle for the City of London (2010-2011), which starts from the silence left by the cessation of financial movements during the weekend in the city of London. This silence is the reverse of the circulation of people and money. The work consists of six locations around the Bank of England and along the Thames Banks. Philipsz proposes to experience this silence from the music that inhabited the city in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before the construction of the Bank of England or the London Bridge[3]. At this distance, the artist transports the ear to another time and makes another tempo in the listener’s ear. Entering another tempo is a way of listening to silence. From the listening of these silences, the sonorous practices continue teaching that the world is certainly heard, but that it is urgent to forge other melodies to inhabit the global city.

[1] The cylinders were forgotten at the Edison National Historic Site and were returned thanks to the Archéophone. They can be heard on this link.

[2] Ballard, J.G., JG Ballard, “The Sound-Sweep” [1960], in The Complete Short Stories, Flamingo, London, 2001.

[3] A fragment of this proposal can be heard here.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)