Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

And once the conclusions of this thesis have been explained, we give way to a closing epilogue, a few words to sum up all that we’ve said so far.

12.5_Epilogue

This section is shaped as a summary of the research process carried out over the past four years in which I’ve been able to analyse the key points of the investigation from a theoretical and critical perspective. As I’ve been able to empirically confirm, we must say that we cannot reach any conclusion. A conclusion closes a process that should be open and that is in fact the actual research in progress that brings meaning to artistic practice. Hence, conclusion as closure is merely another formalism, a space for reviewing all that has been expressed so far, located on the margins. O trajeto é a minha obra, as Brazilian conceptual artist Paulo Bruscky said in 1978 on a postcard, and I think he’s right, although to tell the truth I didn’t realise this until quite recently. I don’t know why, but when I read this postcard I took it to be something like a correspondence card, a visiting or business card, and understood that what it announced was that the personal card – the exhibition invitation card – was his work. A bit like Marcel Broodthaers and his famous invitation to his first exhibition: ‘I, too, wondered whether if I couldn’t sell something and succeed in life. For some time I had been no good at anything. I am forty years old … Finally the idea of inventing something insincere finally crossed my mind and I set to work straightaway. At the end of three months I showed what I had produced to Philippe Édouard Toussaint, the owner of the galerie Saint Laurent.”But it is art” he said “and I will willingly exhibit all of it.” “Agreed” I replied. If I sell something, he takes 30%. It seems these are the usual conditions, some galleries take 75%. What is it? In fact it is objects.’

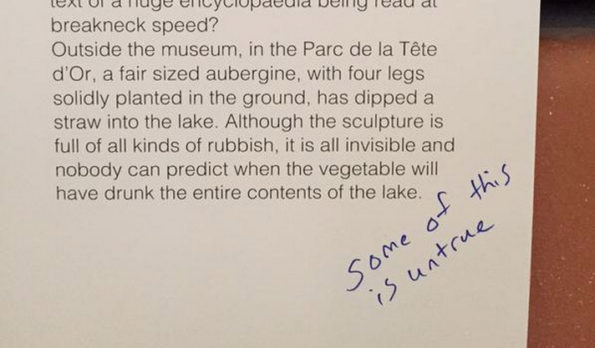

The idea of inventing something insincere appears in one of the most sincere texts I’ve ever read on an invitation card. But to return to our subject, thanks to this confusion I understood the potential of that which remains on the margins of the exhibition. All those elements that surround who knows what (in actual fact, objects), communicational elements that are precisely those that shape meaning, that make it possible, that surround the object and from the margins do not alter its meaning but form it. Like the oldest label in the world – 2985 BC – made of hippopotamus tusk and kept in The British Museum, as we learn from Jorge Blasco’s article ‘Lo que siempre queda del arte’. This label may reveal to us which sandals the pharaoh wore, how he wanted to be remembered and what the status of object was in that specific context. And there’s no trace of the sandals. It’s as simple as the possibility of adding data to objects, definitions that construct their meaning. It’s the power of the cataloguing processes in archives, of the use of labels, of indices of information, of titles. Of words and things. The presumed arbitrariness of associating information to the things that surround us, information that by definition remains on the margin, that accompanies these things. That locates and contextualises. That politicises. Curator and art critic Joana Hurtado will do something similar one day, if someone lets her: she’ll leave the exhibition hall empty and go instead to the archive to recover the material generated by each of the works that will presumably be exhibited. All the labels, brochures, press releases, etc., that refer to each of the pieces will also be on display. Like a palimpsest of sorts, in which we’ll find the different layers of information. Nothing to be seen, everything to be understood. I don’t know whether that’s exactly how it will be, but the fact is that in this way mediation will stand in the middle and the focus will be on the problem of the essentialism surrounding the works. Perhaps the accumulation of information will result in it appearing somewhat absurd, and the subtitlesof the works – bad translations or synthesising summaries? – will appear as another other genre. Along these lines, Ruben Grilo’s exhibition entitled Solo at Nogueras Blanchard gallery, in the brochure too and indeed, in all the texts accompanying the show, we come across the following information: solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo solo. Besides a will to avoid possible bad summaries of the exhibition, perhaps what we find here is a desire to control the space and the conditions that make the show possible, to control how we relate to them and to the context that provides its meaning. We can establish that one of the entrances to the exhibition is indeed controlled, as when Michael Asher switches off the gallery light – or rather, doesn’t switch it on – or when Oriol Vilanova decides that the admission price to the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) is negotiable. By altering the context, we are actually pointing it out, and the fact that there is a context enables us to alter it. On one occasion, photographer and editor Pau Ardid reminded me that my exhibitions were an excuse to be able to write the text for the brochure. I say reminded me because, as far as I know, it was me who had told him that in the first place. And it could well be true, because the fact is that it is indeed in the space of the brochure where the receiver is more vulnerable, probably because of the authority we concede to such marginal information, an authority based precisely on its external component – in theory it’s not your voice – that allows a (critical?) distance from where a (redundant) authoritative discourse can be delivered. The author isn’t just anyone, usually it’s someone who is important in the context that enables the existence of what you’re seeing (a director, a curator, an art critic or someone undefined whose lack of definition makes the text even more authoritative as it appears out of nowhere, in a revelatory way). Such marginal information is also characterised by an apparent agreement between the text and what it presents, which is why we’re surprised when we see that some artists personally alter these texts — as when American artist Darren Bader wrote the famous sentence ‘Some of this is untrue’ on his own labels at the 2015 Lyon Biennale, for instance, or more dramatically, when Antonio Ortega invited artist Mariona Moncunill to work on the brochures of the Autogestióexhibition held at the Fundació Miró in 2017. Bearing these examples in mind, it is obvious that things happen on the margins. What I’m beginning to doubt is whether there is anything interesting in the middle or, as if it were an artichoke, it’s just an empty space. And in the middle of this void, as author Víctor Balcells Matas tells us that poet Juarroz said, there’s a party going on.[1]

[1]Having put down in writing the conclusions of the thesis, now I have to write the rest. I don’t know whether we can derive its premises from a conclusion or whether – as painter Rasmus Nilausen tells us that John Wayne says – shoot first and ask later. But in fact, if prologues always feature at the beginning but is always written at the end, I wonder whether it would be possible for conclusions to be always written at the beginning and placed at the end?

Enric Farrés is artist, professor at the Escola Massana and develops independent editorial projects.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)