Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The philosopher Armen Avanessian (Viena, 1974) emerged most actively on the contemporary art scene with his participation in the ninth Biennale of Contemporary Art in Berlin, in which he presented DISCREET, an intelligence agency understood as a political tool, with the aim of performing and producing actions that transcend. An author of reference within the current of speculative realism philosophy, he has published half a dozen books, some translated into English, such as Present Tense. A Poetics (co-written with Anke Hennig), Speculative Drawing (with the illustrator and visual essayist Andreas Töpfer) and Irony and the Logic of Modernity. He is chief editor at Merve Verlag (Berlin), a publishing house specialised in philosophy and political theory and habitually collaborates with the art magazines Spike, Texte zur Kunst and DIS. He has also introduced, into public discourse, new concepts and theoretical constellations such as “accelerationism”, “xeno-feminism” and more recently the “time complex :post-contemporary”. He says he’d like to contribute a broader vision about the role of philosophical and political theory, which explores the threshold that it shares with art as an action and a practice.

As a theoretical observer of the role of technology in contemporary society, what is your vision of the use of Internet as the dominant means of communication and new technologies in the distribution of contemporary art?

I would like to begin by saying that I believe we are slowly advancing towards a different paradigm in art, as did that of avant-garde or modernist art. My idea –and that of others- is that we already find ourselves, without realising it, beyond the paradigm of contemporary art. But at present I don’t have a better way to denominate it other than post-contemporary art, and as I don’t consider myself a fortune-teller, I’m trying to gather together indications and signs that back up the hypothesis that contemporary art has reached its end.

A form of tracking and analysing this is to contemplate not just forms of production, but also those of the distribution of art. In this sense, the Internet is a specific factor that implies production, distribution, education and the whole economy surrounding it, which is a combination of all these elements. With these factors in play, distribution could change, and I say could, because when one thinks about the Internet, in distribution and contemporary art, what immediately springs to mind is post-internet art, a major subject of discussion in the last few years. In my opinion it failed to a large extent precisely because it didn’t achieve different modes of distribution, even though in the artist sense it has had success in the market. Many of the artists who consider themselves specifically post-internet have aptly dealt with the subjects of the use of Internet as medium/support, have assessed many technological questions, with the potential to reach very different modes of distribution, even though they haven’t managed. On the contrary, they have worked hard to reinforce their stunning success embracing traditional modes of distribution, not precisely on the Internet. We’ve seen them return to galleries, art fairs and even institutions. For this reason I believe that in the future the potential is still lies with the Internet: to show, sell, buy or produce information.

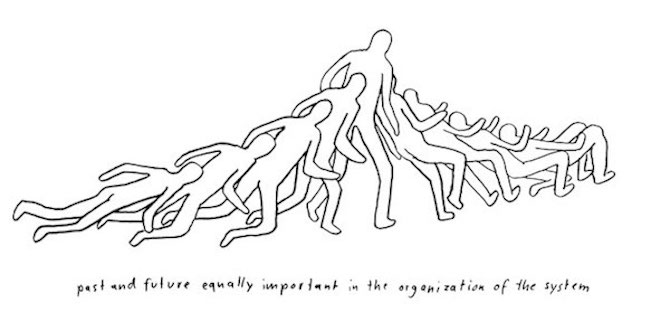

The end of the contemporary has to do with your idea about the “time complex – Der Zeitkomplex[1]Avanessian, A., Malik, S. (2016), The Time Complex. Post-Contemporary, Miami, USA – “where the present time is increasingly governed by predictions of future behaviours?

Well, I would say that there does exist a philosophical argument about time, but in this case, I myself, like Suhail Malik, think that there is a need to abandon contemporary art. The potential lies in that there is still an alternative. Contemporary art entered into the scene when speculative financing and new liberal capitalism picked up the reins already at the end of the 1960s, beginning of the 1970s, and our objective is to find an alternative.

If contemporary art is art of today, that which is produced at this moment in time, do you mean to say therefore that art wouldn’t be produced – at least in the sense that we presently understand it?

No, it’s not that easy. The problem with contemporary art is that it lacks criteria and everything that is done at present is called contemporary art. It can be called “current”, “of today” or “coetaneous”. The contemporary concept merely confuses, as if everything was valid, and I repeat: I believe the problem is the lack of criteria. What interests me is hence why at a specific moment in our recent history is mention no longer made of: “This is a Museum of Modern Art”, so much as “This is an ICA, an Institute of Contemporary Art”. And it’s not due necessarily to the videos being longer or the paintings being greener…

Well, it was about calling the era immediately after that of industrialisation/modernity post-modern, to denote the change of paradigm that affected art as a reflection of society that it is…

I don’t agree. The term “contemporary” is prior to “post-modern”. It already existed in the 60s. I would say that it appeared in response to a new logic, one precisely of production and distribution of art. There have always been paradigms, from the Renaissance up until the Avant-garde, but in contemporary art it adopts a very specific form, with elements that inevitably interrelate: art fairs, large galleries and their impact and the production en masse of artists stemming from universities and art colleges. The role of theory is to study why these elements are specific to contemporary art and indicate signals of change otherwise we accelerate in the direction of contemporary art, which is a speculative neoliberal art. Analysing the market presently and talking in particular about distribution, one observes that there are ever fewer traditional agents. The so-called blue chip galleries[2]A stock exchange term used to talk about stable companies with a high level of liquidity. are increasingly fewer in number a couple of them accumulate all the power, mafia style.

According to the sociologists and economists Nitzan y Bichler, capital functions like power and sabotage, and I sustain that this concept can be applied to the world of art. It is easy to observe how the large auction houses, the large galleries and art fairs work together, banking on a work, on “x” artists and they make them achieve certain prices. It is a system of pure speculation. The curious thing is that the art scene is very critical with regard to content, about capitalism, neoliberalism and speculative finance. But honestly, no one is worried about the content. The artist is perhaps concerned with giving visibility to certain themes, giving lectures on Marx and Žižek connects by Skype at certain events…but the distribution of art is not dedicated to showing the content of the pieces, so much as serving their master as it has always done, and this is proto-capitalism.

The reality is that there is a scarcely any development in the economy of the art market, where the galleries managed by the middle class are practically disappearing and 1% of the existing galleries dominate the market with huge profits. As I said, it is a very corrupt system of speculation, power and sabotage and this is a merely empirical observation. For example, in the previous Venice Biennale– I haven’t visited this edition– there were readings of Marx for months. In contrast, 18% of the large installations the subjects of which were highly political and subversive belonged to five galleries. In this edition, recently inaugurated, the Damien Hirsts, the Gagosian –as the blue chip gallery par excellence, the auction houses, the rich collectors, were all there. On the other hand the phenomenon of flipping[3]A sort of collecting, where work is purchased for subsequent rapid resale., has appeared, the most interesting that has arisen recently, which basically affects distribution, lead by Stefan Simchowitz, the most well known flipper. All of them are players of power and sabotage of contemporary art that control a large part of the distribution.

It seems pretty desolate. Are there other theories that go in the same direction of yours, about the end of contemporary art?

Well I’m an optimist and I see certain indicators of change. A few years ago, David Joselit, who does not adhere to the idea of the end of contemporary art, formulated the hypothesis After Art[4]Joselit, D. (2012), After Art. New Jersey, USA: [Princeton University Press]. In his essay he says that we are in the time after art, in the sense that the ontological justification of art is, and has been always, the production of images. Nowadays, an average individual produces more images than all the artists in history, and this is without counting the machines and automated systems. As such, the production of images stops being the jurisdiction of the artists and what is crucial now is analysing the role images play within the distribution.

So therefore, what is the sense of the constant production of images and their distribution?

I sustain that currently we are facing a great existential crisis, one that doesn’t just affect contemporary art, but also conservative policies or the automobile industry due to climate change for example. But people aren’t bothered, they continue doing everything as ever, we continue driving and manufacturing cars and producing art. I’m not arguing that art has to stop producing images just that it doesn’t make sense and the ontological reason for art is change. Personally I’m more interested in an art that doesn’t produce new images and if it does, that these focus on the effect they have on a network of distribution of the economy of tension. For example, in the last Berlin Biennale, my interest in DIS, the curators, was based on how they worked with certain images, bringing together certain hashtags, and understanding how their circulation online gained a class of traction. Also, on a second level, as a theorist, I believe that there are things to learn from some proposals of post-internet artists present in the biennale, like Daniel Keller or Simon Denny and their contributions towards global societies, technological and economic change: the concept of the “prosumer”[5]“Prosumer”, term coined by Alvin Toffler at the start of the 1970s understood as the growing crossover between producer and consumer and the systems of exchange of blockchain/bitcoin values.

Talking about biennales, what roles do you believe the institutions and cultural industries play in the distribution of art?

Cultural industries, institutions, galleries are all equals and form part of the business. Going back to Venice as an institution: the curator said that she is not part of the market; everybody in the world of art thinks that anyone else is in the market, but the fact is that the artists present in Venice sell the most a few weeks later in Basel. On the one hand a certain legitimisation is required on the behalf of the institutions, from the critics and the rest. On the other hand, I consider that the art institutions ought to have a more dominant and more progressive role, understanding their roles as agents of change, not just realising exhibitions, but also managing facts and using them in a progressive way to produce value and impact the art market.

Drawing to a close, what would be the new logic of the distribution of art?

As I said before, I’m no fortune-teller, but I reiterate that the Internet will function differently. Internet –possibly the most revolutionary technological innovation since the invention of the printing press – and its potential to develop a shared economy or logical platform. Internet has not reached the art world if we compare it with the music industry. To link up with the beginning, post-internet art could potentially be the agent of this transformation, given that works were realised that are seen well on telephones and tablets. Instead, good “vinyl records” have been produced that are exhibited in galleries. Unique objects, art with aura is what capitalism wants, with absurd prices paid by millionaires from Abu Dabi or China: power and sabotage. The transformation of the distribution of art through the Internet is yet to come.

How we consume art has to change, to break with the nostalgic idea of the museum and the artist as a genius producer of images. Musicians also possess genius but they distribute in Soundcloud[[SoundCloud is a free platform for the distribution of music]], they launch their albums on the Internet. The world of (visual) art needs to react to the challenges of our time and to the use of technologies. At present it continues to suppress them and using the Internet simply as a sort of: “Oh, my gallery also has a website”. We have yet to see a radical change, I can’t and shouldn’t say more because theory doesn’t want to and doesn’t serve to foresee the future.

| ↑1 | Avanessian, A., Malik, S. (2016), The Time Complex. Post-Contemporary, Miami, USA |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A stock exchange term used to talk about stable companies with a high level of liquidity. |

| ↑3 | A sort of collecting, where work is purchased for subsequent rapid resale. |

| ↑4 | Joselit, D. (2012), After Art. New Jersey, USA: [Princeton University Press] |

| ↑5 | “Prosumer”, term coined by Alvin Toffler at the start of the 1970s |

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)