Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

When I was studying classical music at the Conservatory, at the height of my obsession to be a better performer, I read Igor Stravinsky’s Poetics of Music. An idea there stuck with me: without a fixed point, there is no movement. For years, I have repeated this phrase insatiably in conversations about creation, although unfortunately I couldn’t verify the exact. What is stated in the book is a similar concept: “And I add: my freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action and the more I surround myself with obstacles. What diminishes constraint diminishes strength. The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self of the chains that shackle the spirit.”[1]Stravinski, Igor. (1977). Poética musical, Taurus Ediciones, p.68 You take away adversity, you take away strength.

Poetics of Music is based on a series of lectures that Stravinsky gave at Harvard University in the 1939-40 academic year. These talks continue today and I was lucky enough to hear one of them seventy years later with Herbie Hancock as the speaker. He explained that when he was playing with Miles Davis, Miles told him: “Don’t play the notes that are obvious in the chord [the four notes that make it up], just the tensions [the ones that grace the harmony].” This limitation helped them create a new harmonic world, floats high above what is obvious. The ear intuits what the chord is and these tensions take it to another dimension. It’s as if a story were narrated in which all the events of the story were already known beforehand, and this lent importance to things that were previously ignored.

It seems that in the field of jazz there is a pervasive permissiveness that opposes the restrictions of classical music, while technique is even more important. Coltrane is considered one of the greatest improvisers ever. Even today, his language, the sound, and the spirituality of his playing continues to amaze people. He destroyed the limits of musical language known until then. It is very interesting, then, that he often refered to a book by a Russian musician little known in the US. Slonimsky, in 1947, wrote several melodic patterns in his Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns, and these figures were the basis of countless hours of musical research by one of the most innovative improvisers in modern music.

Classical music has a huge number of rules, especially in the compositional technique of counterpoint in which melody does not dominate over harmony. The different voices or melodic lines, however, all have the same importance. One of the most complex forms of counterpoint is the fugue, a piece composed around a small melody (subject) that lasts between two and four bars and that contains only the seven notes of the key. This subject has a countersubject with which it always interacts, jumping from one voice to another. All fugues have the same modulations and the same structure. Despite the constraints of this form (or rather, thanks to them), Bach took contrapuntal work to its maximum splendor and even created a literary game, applying his own guidelines. The fugue of the Prelude and Fugue BWV 898 use the letters of his name as the notes on German keyboards to construct the subject.

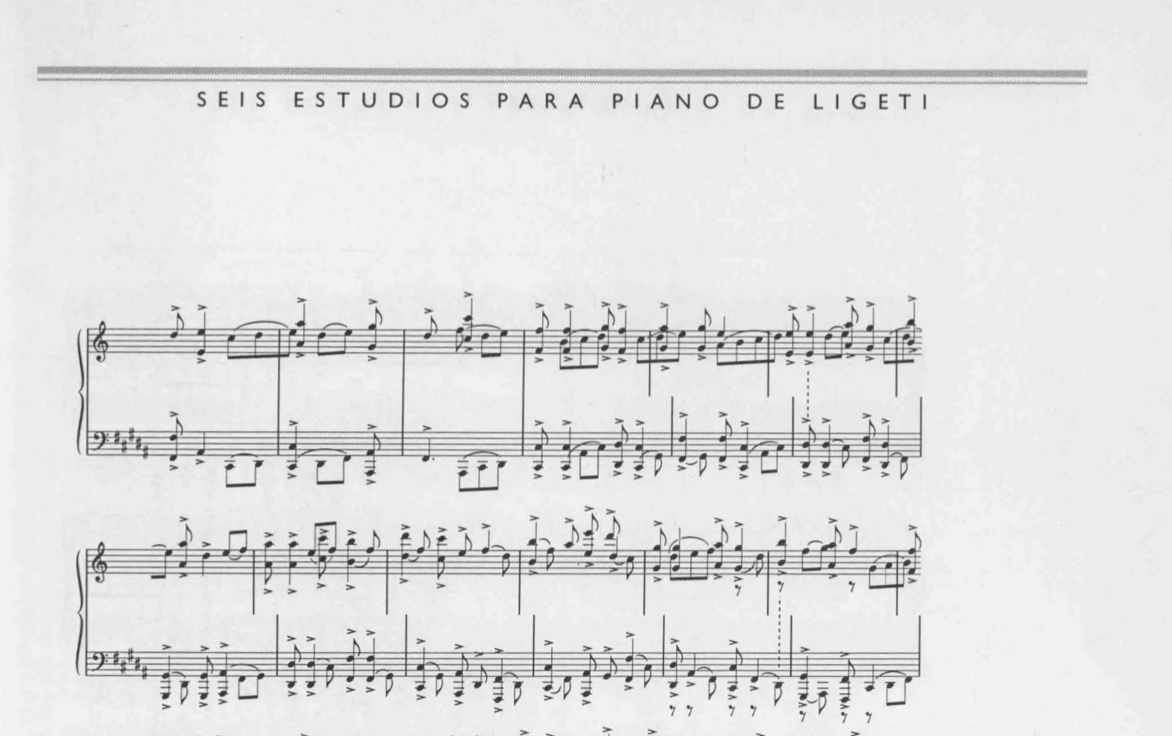

While the German composer stuck to four notes, Ligeti went further and used only one. He wrote a piece in the collection of Ricercata Music in which he uses only the note A. It is a particularly fun and frenetic piece, a rhythmic game of playing the A on the piano in different octaves. Another of the ingenious patterns he invented has to do with the geography of the instrument. Among his piano studies is the so-called Désordre, which is written in such a way that the right hand plays only the white keys while the left hand plays only the black keys. An auditory disorder is created that is opposite of the visual order of the playing.

Returning to Stravinsky’s book, the author mentions two types of music, one linked to ontological time and the other to psychological time. The first penetrates time and identifies with it, while the second does not adjust to the moment of sound and instead is dominated by the will of expression.

In regards to the first type, all the jam sessions I’ve ever participated in come to mind. In improvisation time is not felt, there is only the present and presence. This liberation of the mind, of being conscious, of just listening, means that there is no time to think about everything you could play. It is precisely this vertigo of infinity that Stravinsky speaks of: “Will I then have to lose myself in this abyss of freedom? To what shall I cling in order to escape the dizziness that seizes me before the virtuality of this infinitude?”[2]Ibid., p.67 In jam sessions, one has the feeling that the music already exists and you simply have to be receptive to bring it into the physical world. There is no desire for personal expression and limitation is created in the way that the music is channeled.

With regard to music linked to psychological time, at the moment of composing, the limitations can be set by the work itself. When you are in tune (literally) with what is revealed, your instinct is awake. The expression “the song tells me to…” shows that one is at the service of what is being created. It is also very common to say “I can’t find the chord,” which implies that it is already there but has not yet been discovered.

In terms of performance, the most liberating limitation related to piano was a piece of advice from Kenny Werner. In his book Effortless Mastery, he proposes to play a single note and listen to it until it fades away. He recommends it because when first studying an instrument it is very common to try to play a lot, very quickly and to perfect the technique in the shortest possible time. He suggests the opposite: to have the piano in front of you, the eighty-eight notes with its strings, and to not use the pedal to lengthen the sound but rather to play just one note, putting awareness in each muscle, in each finger, listening to what it generates, until the sound wave disappears by itself.

If I think about the chains that bind the spirit that Stravinsky talks about, I feel that mental noise is the most significant. By giving space to a single note and surrendering to deep listening, I discover that I free myself from myself and that this generates the silence needed to make music.

(Front image: Bach manuscript)

Meritxell Neddermann is a pianist and composer. She studied classical music and then studied modern music in Boston. After living in New York for three years, she returned to Barcelona and recorded her first solo album (“In the backyard of the castle”, 2020). Apart from official studio recordings, she loves to experiment with loops, vocoder or synthesizers to find in the physical field what she has in his head. She is currently touring with Jorge Drexler and recording her second album.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)