Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

I’m thinking of the doorsill as a place marking the difference between inside and outside. How we linger there, talking to friends who drop by for a visit on a post-lockdown evening, not allowed to come in by government rule. Opening the door for someone and hugging them while entering, in the small awkward space of the entrance. It reminds me of the teacher, standing in the doorway of the classroom, greeting the students one by one as they come in. Marking their presence, making students aware that they are entering the space of the teacher and the teacher’s rules. The power relations that are represented in the doorstep, as a threshold – representing the spaces in between, in between rooms, inside and outside. It makes me think of the door as an object to close off spaces, but to keep them open simultaneously, as a place of entering but also of leaving. The last look goodbye, looking over your shoulder, closing the door behind you – a door too old to properly shut by pushing it, you need a key.

The doorsill takes up a place in the home, the school, the building, but it is a metaphysical space as well. A transitory space, a space of hiding and of showing, of choosing what to reveal and what to store behind. And it is a space of gatekeeping, of deciding who can enter and who cannot.

The doorstep and its frame are there to remind us of the act of passing through, of transitioning from one space to another. The artist David Bernstein materialised this in his artwork ‘Reminder’ (2014-2019), a series of small wooden wall-hung objects, with smooth surfaces and diagonal edges. This object refers to and is reminiscent of the Jewish tradition of hanging a mezuzah on the doorpost of a home. An object of everyday significance, according to Bernstein, the mezuzah generally consists of a small tube of varying materials, encasing a piece of paper or parchment with inscriptions of worship. According to the tradition, they are supposed to be put at each doorway in the house to remind the person of the change from one space to another. The ease with which we do this in our houses, how we walk from room to room forgetting what we were supposed to do or why we came to the other room, and the contrast and discrepancies of other door spaces, fictional or intangible gates, which require more thought and difficulties to pass.

David Bernstein, Reminder, various wood and neodymium magnet, dimensions variable (2014-19). Photo by LNDWstudio. [1]The work contains a blessing adapted from different blessings for hanging the mezuzah that one can recite while hanging the work. Bernstein states he wants to consider the value of Jewish religious … Continue reading

Doorways are not only passages, they form spaces in between, separating and obscuring what is behind the door. The poet Rodaan Al Galidi wrote about keeping the door of the fridge open to show the light hidden inside. He dedicated a collection to it, Koelkastlicht, 2016 (translated as Fridge Light), where he reflects upon his never ending stay in an asylum seekers’ centre in the Netherlands. The poems talk about being in the dark and in the cold, like the fridge light when the fridge door is closed, and remind us of the lives put on halt in such centres, sometimes waiting for years until being allowed in society.

Rodaan al Galidi, Excerpt from a poem of the collection Koelkastlicht (2016), translated by David Colmer for Poetry International (2017). Originally written in Dutch, only a few of Al Galidi’s poems have been translated into English, available on the Poetry International website.

Al Galidi also wrote prose about his experience as an asylum seeker, most notably in his book Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (which roughly translates as How I became talented at living), published in 2016, and more recently in his novel Holland (2020). His work visualises how the migration system reiterates, albeit less physical or material, the historical concept of gates, the only place through which one could enter the city walls as an outsider. Keeping people in a facility while administrations judge if they are allowed a life in society, or obliging people to fulfil a test before granting residency rights, the cold and the darkness many people are forced to live in indeed. Invisible, like the light hidden behind the fridge door. The fridge door as a reference to a collective trauma, imprisoned in bureaucracy.

Right: Part of the former city wall of Rotterdam, unearthed during the construction of the Rotterdam Blaak train station, suspended in the underground part of the train station in the exact location where it used to be standing. Copyright Rotterdam Daily Photo.

Cities still show traces of their former city gates, now hidden behind hotels, in metro stops, the former walls incorporated in other buildings. These doors were the main spaces of gatekeeping, protected by guards. In my imagination, they followed similar choreographies as the English royal guards at the Buckingham Palace still do on a daily basis, with their high black hats and red military vests. Many cities had specific rituals for closing the city gates at night, every night, picking up the keys from a safe space, locking the door, and putting the keys back safely while other people would light the city’s candles, or oil lamps, going on a second round towards the early morning to ensure they were still burning. How some cities forbade non-locals to stay overnight in times of crisis or epidemics, and how the concept of stranger or alien represented everyone who was not a resident of the city, even if they were born in another city only ten kilometres away.

We may have lost the rituals and the tangible spaces of these old city gates and doors, but the gatekeeping, ambiguous definitions of insiders and outsiders, the difficulties of passing through the gate still exist in present-day societies.

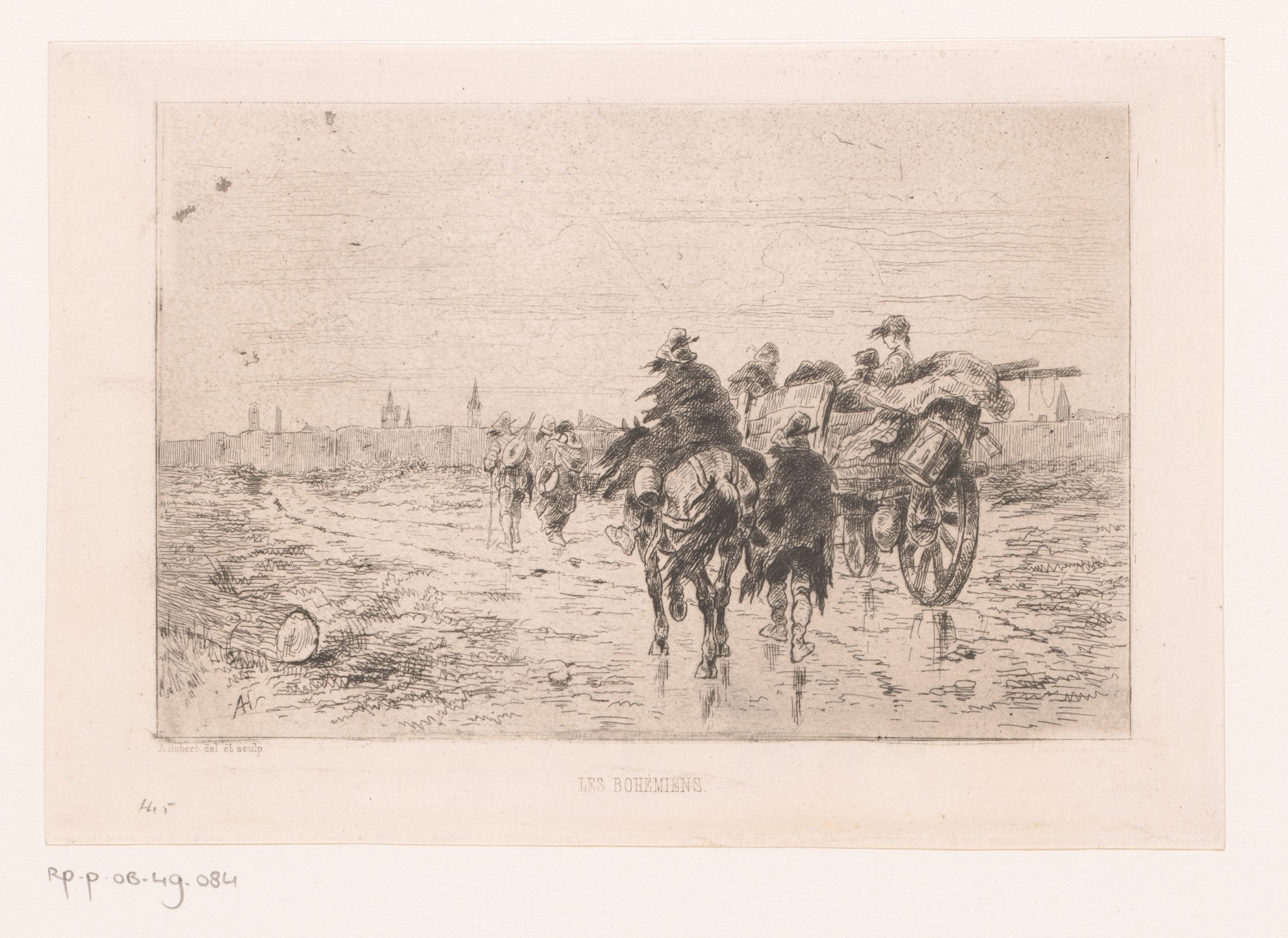

A group of travellers in and surrounding a carriage approaches a walled city. Les bohémiens, lithography by Alfred Hubert (1879), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

The European history of gates is not linear, it didn’t progress from moderate to strict migration regulations. Instead, cities open and close their towns to outsiders depending on the circumstances which often significantly differ in specific times and spaces. Whether regulations were more inclusive or exclusive, depended, among others, on the local labour market, the interests of local elites, characteristics of migrant groups and relations between the host and the guest societies. For example, in the 19th century, Amsterdam allowed everyone to enter the city without documents, since they needed labourers for the fleet. They were allowed to enter but the door remained ajar. These people did not have access to welfare – in case they lost their jobs, got an accident or fell ill, they were on their own and would have to return to their home cities or villages again. Late medieval Bruges even made policies to attract skilled textile artisans to expand the local industry. Here, instead, social policies were opened to these newcomers, as a strategy to attract them to compete in order to compete with other cities. Different doors for different people, as is still the case in the Low Countries today. From Rotterdam’s housing policy to Amsterdam’s expats to the homeless people in Brussels – different limitations and stimulations exist for different people and leave them in different positions: being inside, outside or in-between.

Jason Hendrik Hansma, Untitled (Traverse), Cast concrete, beeswax (2020). 50cm x 10cm x 5cm. Photo from the exposition A centre cannot hold, Memphis, Linz (2020).

Who is placed inside, outside or on the brink of a door reveals a big deal about societies. They show signs of their ideology, economic interests, and international politics of communities, but also prejudices and privileges of social groups. Doors function as portals and as gates, separating spaces and separating bodies, the doorsteps representing the passage and the in-between. They are places of traverse, but they also form spaces with a wider meaning – a limbo for those trapped in the politics that surround doors, that allow people to enter or leave a place.

My two home countries, Belgium and the Netherlands, still contain such intangible doorsill-like spaces such as the legal situation of undocumented migrants, or asylum seekers, or people with a precarious or temporary residency permit. People who are present on the territory but have a smaller set of rights and entitlements than local citizens. People who work and contribute to society especially in the cases that are at the foundations of the economy like those of low wages in care, construction and beauty sectors. Employers and authorities profit from their being in limbo, looking the other way.

The violence of the doorsill is perpetuated in many forms. During these past months in Brussels one could enjoy an ice-cream at the fountains of Sainte-Catherine while two streets down from here at the Béguinage church, hundreds of undocumented immigrants refuse to eat anything. They chose the most extreme form of peaceful resistance – people without papers, without rights, obliterated by the law – asking for help to be recognised and regularised after years or sometimes even decades of living in uncertainty. Some stating they would rather die than continue living without papers, in the shadows, in between. [2] The hungerstrike in Brussels is organised by the Union pour la Regularisation des Sans-Papiers, a group of about 700 people who have occupied public buildings in the city to call for attention for … Continue reading

Even though doors change their shape, these questions remain: How large is the door frame of a society, how high is the doorstep, how many people can pass through the doorsill – and which people, most of all, do so, without realising, without touching the doorstone.

It’s not you, bad doors are everywhere, rue Paul Devaux 3, Brussels. A panel on the street exposing a series of installations about doors, keys and portals by guests (2020-ongoing); initiated by D-E-A-L Brussels (Morgane Le Ferec, Quentin Jumelin and Victor Coupaud). See all installations at https://baddoors.space/.

(Featured Image: Part of former city wall of Brussels, called Tour Anneessens, now hidden in a backstreet in the city near the Anneessens square. Photo by Myrabella, Wikimedia Commons)

| ↑1 | The work contains a blessing adapted from different blessings for hanging the mezuzah that one can recite while hanging the work. Bernstein states he wants to consider the value of Jewish religious objects and rituals as something that is not only for Jews, but available as wisdom for anyone who is curious. The blessing goes: Blessing for Reminder I am full of love and gratitude for all the blessings and wonders of this world. Thanks to the unknown, for both the worries and the curiosities. I give thanks for the presence of mind and body. As I enter the space or the space in my head, remind me to release my armor and the weight of the outside world. As I leave, wrap me in support and protection. Reaffirm who I am and all the qualities placed inside me. As I install this reminder, I affirm a new sense of home. May this home be a reflection of inner truth and be a place of hospitality extended with grace and sincerity. May my doors be wide enough to receive those who hunger for love, friendship, and joy. Remind me, Hineni, I am here. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The hungerstrike in Brussels is organised by the Union pour la Regularisation des Sans-Papiers, a group of about 700 people who have occupied public buildings in the city to call for attention for the situation of people in precarious or irregular stay. But there are thousands more undocumented migrants in Belgium, estimates say about 150.000 people. The Covid-19 pandemic has only worsened their situation. See also the interview with Modou, spokesperson for the Voix des Sans-Papiers Bruxelles. The notion of the violence of the doorsill presented here is not new, nor unique to the situation of undocumented migrants. I focus on migration status, but it also resonates in institutional racism, gatekeeping and other systemic forms of social inequality. See for example W.E.B. Dubois’s notion of the veiled perspective presented in his anthology Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil (1920). Recent publications in Belgium and the Netherlands include amongst others the call for decolonization of Ghent University (2020) and the Decolonize KU Leuven manifesto (2021), the book Being Imposed Upon edited by Heleen Debeuckelaere and Gia Abrassart (2020), the edited volume De Goede Immigrant by the team of Dipsaus podcast (2020) or the Zwart Manifest (Black Manifesto) for the Netherlands (2021). |

Marjolein Schepers is a researcher of social history, living and working in Brussels. She focuses on dynamics of inclusion and exclusion and on migration and mobility in historical perspective. Her current research uses maps, archival material and geo-visualisation methods to analyse changing urban infrastructures in the Low Countries in the 18th and 19th centuries. Next to academic research, writing and teaching, she participates in activism for migrant rights and collaborates with artists and writers.

Photo: Hasret Emine

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)