Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

A bundle of electrons interacts with the surface of a sample coated with an extremely thin layer of carbon that acts as a conductor. The exchange of energy between the electron beam and the sample results in the reflection of high-energy electrons. A detector composed of lenses based on electromagnets measures the quantity and intensity of the electrons returned by the sample. The result is a high-depth-of-field and realistic-looking digital image with a resolution of 0.4 to 20 nanometers. It is a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that has produced an unprecedented image of something invisible to our eyes: on a bee’s wing, there is something that prevents it from flying and carrying pollen as it should. What is it? It is particulate matter suspended in what we call air pollution in urban environments, mainly from fossil fuel emissions, tire and brake pad wear particles, which has been deposited on the bee’s wing.[1] https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2009074117

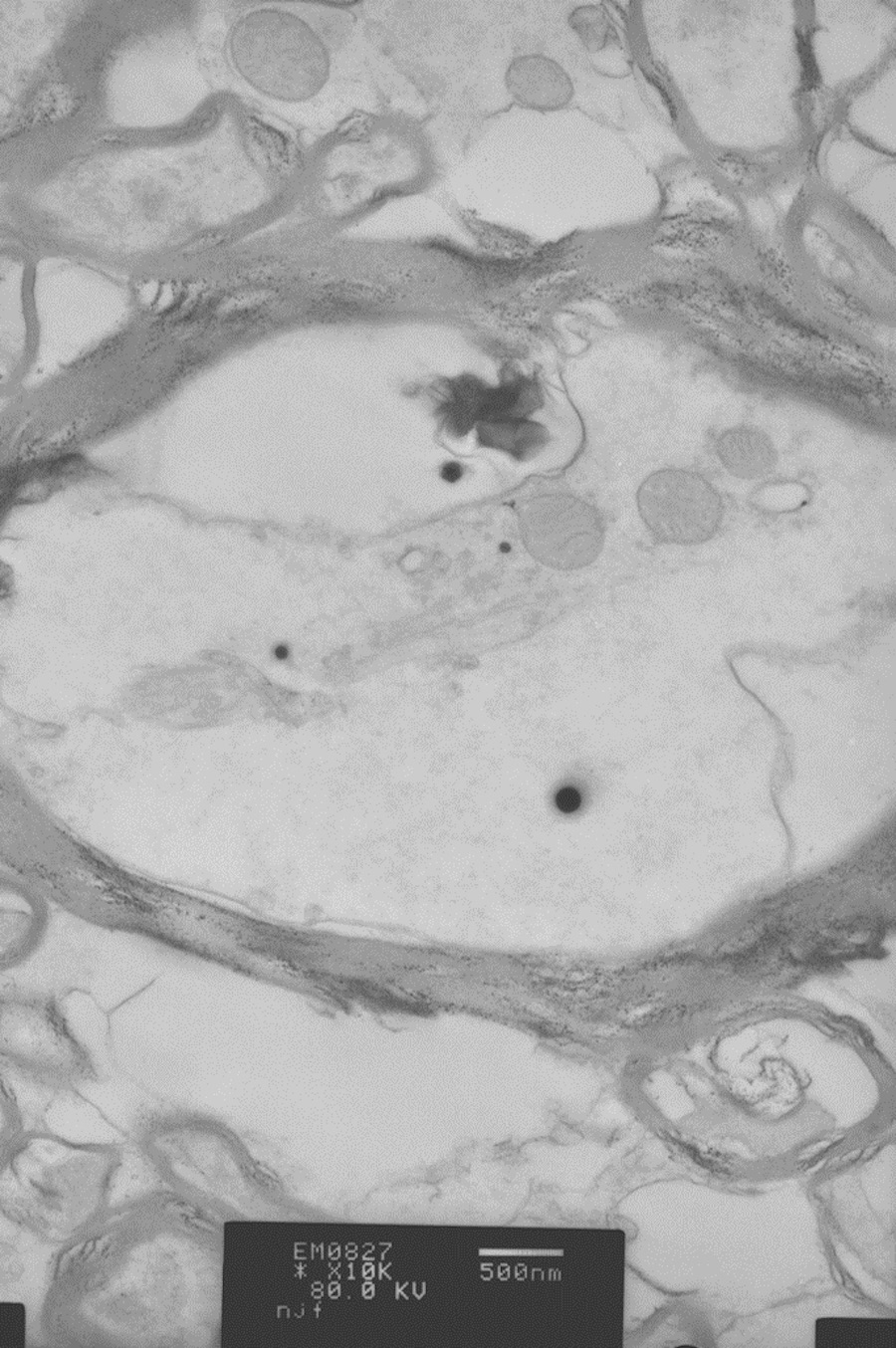

Transmission electron micrograph of brain thin section, identifying magnetite morphology rounded particles. Barbara A. Maher et al, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605941113.

Another recent unprecedented SEM image of a human neuron section identifies the presence of anomalous circular particles. Analysis of these particles reveals that they are spherified magnetite suspended in air pollution as a byproduct of burning petroleum derivatives in combustion engines. The magnetite nanospheres can directly enter the brain through the olfactory nerve when inhaling air, and the body does not eliminate them; they deposit and, given their magnetic properties, alter neuronal function.[2] https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1605941113

And at the same time, the SEM technology that allows us to capture the materiality of the air is made of the same anthropogenic matter that is recorded in the SEM images. The microscope requires steel produced at high temperatures. The sample needs a layer of carbon or metal like gold. The resulting image is digital. All this material and digital matter requires the extraction of increasingly scarce and difficult-to-extract materials that produce the dust we breathe. The entire process requires energy, which is still mostly of fossil origin, producing toxic health gases such as NO2 and CO₂ emissions that increase the greenhouse effect and alter climate and living conditions.

These two images challenge us. What do we know about the materiality of the air? Is air more than a fragile equilibrium percentage, among other gases, of oxygen (20.95%), nitrogen (78.08%), argon (0.93%), and carbon dioxide (0.035%)? What else is suspended in it? What is in the air that leads the WHO to claim that there are more than 7 million deaths per year from air pollution? What presences, new materialities have invaded the air? To what is this new materiality due? Since when? Why? Does air make us? Are we what we breathe? What do we know about its effects on human and non-human behavior and health? Is our survival “suspended”? What does it mean to be “in the air”? How do we understand the capacity to alter the balance of life on a scale invisible to our eyes? How do we comprehend the infinitesimal scale, understanding that the seemingly small presence of magnetite nanospheres greatly alters our brain, how do we understand that the seemingly small proportion of CO₂ on the planet radically alters our living conditions (from 320 ppm in 1960 to 417 ppm in 2022)? How can culture, artistic practices help us experience the materiality of the air to imagine other possible worlds?

To breathe pure air, we would have to go to the Southern Ocean [3] https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2000134117 . That is the magnitude of the human footprint on the air. The phrase “everything solid melts into air” from Engels and Marx’s Communist Manifesto in 1848 now takes on a literal dimension. Human activity, in the form of a great acceleration, since the 1950s, is present everywhere at the nanoscale as aerosols. Let’s take a deep breath, what we breathe is metallic air, the 21st century is the century of dust (Parikka, 2015). There are no aspects of climate and environmental change more critical than those affecting health and well-being, and none are more urgent than those affecting the most vulnerable. Atmospheric pollution and climate change belong to both categories (Neira, 2022). There is no doubt that the skies are closing. But we share the universal right to breathe (Mbembe, 2020). Pollution is colonialism (Liboiron, 2021). The air is under attack, but inertia in how we understand economy, development, and progress blurs the imagination and audacity to explore other paths. It is easier to imagine living without air than without capitalism (Herrero, 2022). What does it mean to be “in the air” culturally, politically, and medically? Do we need a cultural conception of climate as a medium? (Horn, 2018).

We live submerged at the bottom of an ocean of air, which through unquestionable experiments, it is known to have weight (Torricelli, 1644). A weight that now not only responds to a density of 1.225 kg/m3 at sea level at 15°C, which varies depending on altitude, temperature, humidity, etc. An air that must make life possible but that the human civilization has radically transformed its composition and turned it into a medium for transporting infinitesimal toxic particles due to the indiscriminate use of fossil fuels. The COVID-19 pandemic allowed us to put into crisis the foundational belief of modernity, in which there is a clear implicit distinction between human things, natural things, and technical or artificial things, and allowed us to experience that it makes no sense to practice a way of being in the world in which “we”, humans, are separated from ecology, from nature.

It would be necessary to interweave practices, knowledge, and affects related to ways of living and being, making environmental, social, and mental ecologies totally inseparable (Guattari, 1989). By focusing on the air we breathe, the air would no longer be something invisible that remains between what we see. We would be ecological when we breathe, knowing that each human is a planet that contains billions of microorganisms; that polluted air impacts human health and other species with whom we have a symbiotic relationship, such as bees; that we breathe in a social respiration, a collective respiration, formed by the network of relationships between various agents, objects, and sensibilities that are recognized from their fragility and interdependence and are mutually valued. Feeling and thinking ourselves to act accordingly.

The awareness that we cannot breathe in the most literal and metaphorical sense is spreading globally. The individual cry is now a collective cry, political-social, ecological, cultural, and artistic. “We can’t breathe” is becoming the phrase that most radically defines the state of vulnerability and global urgency in which we live. Achille Mbembe claims the universal right to breathe[4]Achille Mbembe, «The Universal Right to Breath» https://a-desk.org/en/magazine/el-derecho-universal-a-respirar/. Maria Arnal sings: “the air doesn’t belong to anyone”.[5]The song is track 3 of the album Aria by Maria Arnal and John Talabot, created together on the occasion of the project Air/Aria/Aire curated by Olga Subirós and presented at the Venice Biennale … Continue reading

THE AIR SINGS: ARIA

At the heart of the air

a right is smothered

the right of the leaf

the right of the bird

the deep gill

the beast of the future

at the heart of the air

clean air dies

who does the sky belong to?

the sky inside and out

who does the sky belong to?

the sky outside and in

no skin and no boundary

lungs and paths

inside the atmosphere

the atmosphere inside

at the heart of the air

the future is smothered

the right of the bee

the right of the catfish

the deepest root

the beast the right

at the heart of the air

clean air dies

the air that I exhale

and that you inhale

the air that I inhale

and that you exhale

at the heart of the air

clean air dies

the air that is life

that does not belong to anyone

the wind rose

with a thousand movements

asks a question

of everyone present

a carnation can do no more

than it does

what will you do, humans,

when you cannot breathe?

at the heart of the air

clean air dies

the air that is life

that does not belong to anyone

in the eye of the hurricane

there is calm

at the heart of the air

the future is smothered

clean air dies

clean air dies

who does the sky belong to?

the sky of the present

who does the sky belong to?

the sky of the future

at the heart of the air

clean air dies

the air that is life

that does not belong

to anyone

Maria Arnal

“El peso del aire” is a collaboration with A*Desk about the project on AIR that will take place at the Bòlit, Centre d’Art Contemporani de Girona from February to May 2024 and is co-commissioned by Olga Subirós and Ingrid Guardiola with the participation of Abelardo Gil-Fournier and Job Ramos[6]Conversation between Abelardo Gil-Fournier and Job Ramos, Aire, Fito Conesa[7]Fito Conesa, Anoxia, 2023 , Mireia c. Saladrigues[8]Mireia c. Saladrigues, En suspensión , Pep Vidal[9]Montse Badia about the work by Pep Vidal , and the special participation of Maria Arnal and John Talabot[10]María Arnal and John Talabot .

[Featured Image: Micrograph of a Giant Asian honeybee (Apis dorsata) wing region obtained with a Zeiss merlin compact VP microscope at 1 kV EHT and 460X magnification. Geetha Thimmegowda et al, doi:10.1073/pnas.2009074117]

| ↑1 | https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2009074117 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1605941113 |

| ↑3 | https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2000134117 |

| ↑4 | Achille Mbembe, «The Universal Right to Breath» https://a-desk.org/en/magazine/el-derecho-universal-a-respirar/ |

| ↑5 | The song is track 3 of the album Aria by Maria Arnal and John Talabot, created together on the occasion of the project Air/Aria/Aire curated by Olga Subirós and presented at the Venice Biennale 2021. https://ariamariaarnaljohntalabot.bandcamp.com/album/aria |

| ↑6 | Conversation between Abelardo Gil-Fournier and Job Ramos, Aire |

| ↑7 | Fito Conesa, Anoxia, 2023 |

| ↑8 | Mireia c. Saladrigues, En suspensión |

| ↑9 | Montse Badia about the work by Pep Vidal |

| ↑10 | María Arnal and John Talabot |

Olga Subirós is a curator, architect and exhibition designer. Her projects adopt an integrative point of view on the culture of the 21st century and the transformations of the digital era.

www.olgasubiros.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)