Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

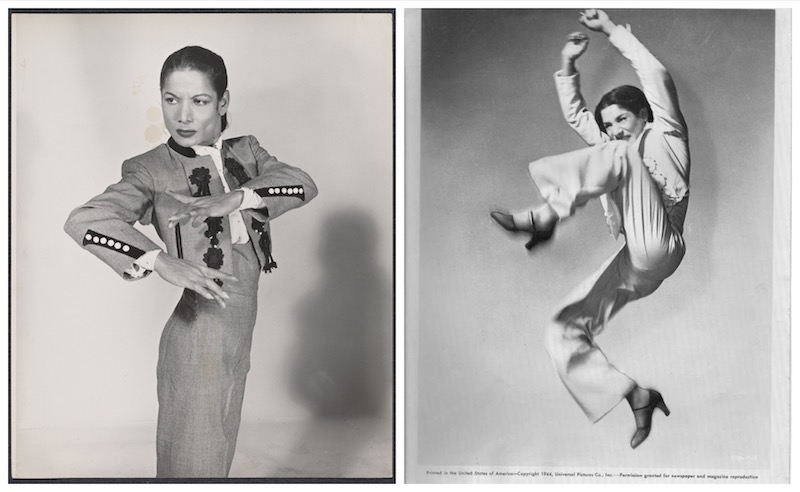

Queer and post-categorical desire have been sharing the stage with flamenco for the past few years. Three references link these apparently distant phenomena: the Flamenco Queer project, founded by the guitarist Jero Férec and the dancer Rubén Heras; the work of the thinker and dancer Fernando López, materialized in Queer History of Flamenco; and the world of dancer, choreographer, and director Manuel Liñán, who is the last and the only one who has not self-designated as queer, though without escaping categorization for that (The New Yorker dedicated the Flamenco Queer mini-doc to him in 2021), as sex-gender identity belongs largely to the Other’s gaze.

Bringing flamenco together with the post-foundational impulse of queer theory implies asking questions, and here we will do it by focusing on dance and also a series of conversations with Liñán himself (whom I deeply appreciate for exchanging WhatsApp audios and reflections) on the kind of exclusions in dance correction related to gender-based roles. The unalterable, heavyweight of tradition that falls upon all flamenco work, together with the frenetic rhythm of the art market and its imperative for creativity, means that the oscillation between anachronism and avant-garde, or tradition and subversion, must be contemplated beyond the terms of a personal, “aesthetic rupture” of so-called contemporary flamenco.

“Like doves, girls, like doves! Hands like doves” is one of the lines that every teacher uses to motivate a flamenco attitude. Not only because of the poetic nature of the expression, but because it refers to the great Matilde Coral, protagonist of Saura’s Flamenco, conservator and systematizer of the Sevillian School of Dance[1]The Sevillian School is a style of dance, focused on a “woman’s dance” that seeks to highlight femininity, sensuality and flirtatiousness, placing great importance on the movement of the … Continue reading, to whom the expression is attributed. That reiterations makea subject and makea body is something that the theory of gender performativity has taught us very well. Manuel, not like a dove, not you; not with that long, tight dress; careful with shaking those hips and hands, Manuel, that’s too effeminate. Liñán tells me that after suffering this corrective gender violence throughout all his childhood and, on occasion, in adulthood, giggles always broke out among his rehearsal partners: abjection must also be repeated, remembered, and maintained over time to be effective. This is the reason why Sedgwick considers queer people to be those “whose subjectivity resides in denials or deviations from (or through) the logic of the heterosexual supplement.”[2]Sedgwick, E. Touch Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, 2002. In short, all those that, rather than hang on a performative repetition of the genre, gravitate around explicit denials of performativity, which the author calls periperformative.

“I had no idea what it meant to be queer. When we premiered Viva!, friends and journalists told me I was a queer dancer and I had to look up what that was.” The fact that Manuel confesses this to me, apart from a blow to the narcissism of theory and a confirmation that the history of art is anachronistic, as Didi-Huberman announces, opens the link between flamenco and queerness to criticism. In Historia queer del flamenco(A Queer History of Flamenco), it appears that the first written example of the word flamenco to designate a musical and choreographic style dates back to 1847. Less than forty years later, we find the first reference in the newspaper El Alabardero to the feminization of the dance taking place at the end of the 19th century. “The most high-class and exclusive personalities in the social scene in Madrid are just dying to hear the cries of cante jondo and to see gypsies and men of dubious gender dance[3]López, F. Historia queer del flamenco. Desviaciones, transiciones y retornos en el baile flamenco(A Queer History of Flamenco: Deviations, Transitions and Returns in Flamenco). Barcelona, 2020, p.42..”

Manuel Liñán does not reject the term queer, although he prefers to enjoy the pleasure of “non-labels, because I have been overwhelmed at times by categories.” He does acknowledge having learned that it is necessary to combat the intransigence that still remains in the teaching of proper, traditional flamenco dance. However, in light of the previous quote, “what we call queer today already existed in flamenco before the 90s.” Two consequences: on the one hand, the queer history of flamenco is anachronistic, especially talking about those “men of dubious gender” from the end of the 19th century with categories from the end of the 20th century. On the other hand, Manuel tells us that these already existed, that his style is repetition and difference (purity and evolution, tradition and avant-garde, orthodoxy and subversion, as most critics have liked to define him) and “it is thus recognized that making history is making, at least, an anachronism[4]Didi-Huberman, G. Before the Times: The History of Art and Anachronism of Images, 200[ ],” that is, to choose an object of study from a current interest. And this is so, according to … Continue reading.” Imitating Didi-Huberman, who finds three overlapping times in Fra Angelico’s murals, we take Viva!, the most famous of Liñán’s work, and evoke with it the anachronism (or intrusion of one time into another) that seems internal to the objects themselves. Three times: (1) the impeccable execution of the choreography in all its facets, respecting what we understand as tradition, with its respective styles and resources, and which has led Liñán to be described as an orthodox dancer respectful of that which is consecrated; (2) the subversion of the gender binarism in the aesthetics of the work that, in contemporary terms, has made his dance be equated with transformability and creativity, compared to the static and rigid character (both categories understood here in temporal terms) of classical masculinity and femininity; and, finally (3), the time which he intends to transport us to, a remembered, childhood past, with certain tools of the present from which the body of dancers narrates a distant, bygone era, through an aesthetic that emulates the tablao dancers of the 1960s and 70s[5]Without wanting to attribute practices of drag to Liñán, it should be noted that he shares, in this case, the double meaning of drag: that is, to cross genders, on the one hand, and cross time; … Continue reading.

This last idea converges with the objective of queer medievalists like Carolyn Dinshaw who try to break with the demonization of transhistorical categories or, in other words, of anachronisms: “As queer historical projects aim to promote a queer future, the possibility of queernesses in the past –of lived lives or fictional texts– becomes crucial[6]Dinshaw, C. Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern. Duke University, 1999, p.140..” But this does not suppose a unified identity between subjects of the present and the past, but rather an anachronistic and fanciful memory of partial and affective contacts between marginalities from different eras.

Liñán narrates, in many of his performances, intimate stories: the frustrated desires of childhood regarding his aesthetics, expressed in Reversible, or the bittersweet bond with a father whose goal was to see his son become a bullfighter in Pie de Hierro(Iron Foot). I mention this intimate but evocative, memory construction, generator of ties and community, because adopting a story is also ritualizing it through art. Manuel was happiest in the interview when he told me the relevance that his aesthetic commitment has had in the naturalization of the long, ruffled dress called bata de cola: “The bata de colaalready exists, no one needs to justify themselves or to create a character. I think it is very important that Viva! has become part of a queer memory, that my childhood memories have inspired young people who are studying flamenco to write to me and tell me that they follow me, that I am a reference to them.”

| ↑1 | The Sevillian School is a style of dance, focused on a “woman’s dance” that seeks to highlight femininity, sensuality and flirtatiousness, placing great importance on the movement of the hands, shoulders and hips and reinforcing the use of traditionally feminine resources such as the bata de cola, shawl and castanets. On the other hand, a typically masculine dance would accentuate the precise, forceful footwork and verticality in movements. This division has been and is used to correct dance, even though ever since the emergence of flamenco there have been subversions and deviations that have turned abstract ideals into multiple forms, from La Cuenca, Edmond de Bries, Miguel de Molina, Carmen Amaya to Israel Galván and Rocío Molina. Fernando López also points out that as of 2010 there has been an explosion of discourses and practices that question the rigidity of gender, of which Manuel Liñán stands out as the principal reference. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sedgwick, E. Touch Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, 2002. |

| ↑3 | López, F. Historia queer del flamenco. Desviaciones, transiciones y retornos en el baile flamenco(A Queer History of Flamenco: Deviations, Transitions and Returns in Flamenco). Barcelona, 2020, p.42. |

| ↑4 | Didi-Huberman, G. Before the Times: The History of Art and Anachronism of Images, 200[

],” that is, to choose an object of study from a current interest. And this is so, according to Manuel, even for the most traditional forms, because we never stop “channeling an art with a lot of history and tradition from our own perspective and current interests.” And this is the crux of the matter. The inclusion of the subject of temporality has been a constant in queer theory since its early development, for one of its shared premises is that sex-gender identity is the result of the substantializationof events over time. It is around the mid-2000s onwards that there is talk of a temporal turn that unleashes a debate around queer temporalities with two very clear tendencies: one that projects queerness onto the future and another that projects it onto the past vindicating anachronism (that demon of history, as falling into anachronism is not making history) within theory. “One of the most important reasons why my dance has been defined as innovative and creative is because of the transgression of the gender roles I adopt in it.” Liñán is concerned that critics focus too much on gender issues, since “it’s my aesthetic and inseparable from my dance.” However, immobilizing the temporal focus in this point does not allow us to perceive how, in reality, “the history of images is a history of temporarily impure, complex, overdetermined objects. It is a history of polychronic, heterochronic or anachronic objects[n]Ibid., p.46. |

| ↑5 | Without wanting to attribute practices of drag to Liñán, it should be noted that he shares, in this case, the double meaning of drag: that is, to cross genders, on the one hand, and cross time; transporting himself to a past of female bodies that Elizabeth Freeman, with her notion of temporal drag, describes as “blasphemous living museums.” |

| ↑6 | Dinshaw, C. Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern. Duke University, 1999, p.140. |

Patricia Lara Folch (1996, Tarragona) has a degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (UC3M). Master in Philosophy of History and Master in Interdisciplinary Gender Studies (UAM). She is currently working as a FPU researcher at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, where she is working on a doctoral thesis on queer temporalities. Her interests focus, above all, on the confluence between gender studies and contemporary political philosophy.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)