Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The following passages are taken from my forthcoming book Future Metaphysics (Polity, 2019), that attempts to restate the importance of the great metaphysical categories (substance and accident, form and matter, life and death, etc.) for the present and giving them an unexpected twist. What if the idea of accident, for instance, had to take into account the many new kinds of glitches, crashes and crises —from finance to ecology, from technological catastrophes to social collapses— that permeate our culture and make everyday news? Can we keep on using this concept as it was traditionally meant to be used when risk and chance have become part of the very substance of our world, so rendering the distinction between substance and accident meaningless? To what extent do we witness a return of theological (wishful) thinking in current Silicon Valley ideologies of trans-humanism, dematerialisation or immateriality? And finally, with regard to the A*DESK topic of the month, could it be that we are living not just in a fundamentally new (digital) time, but time itself has changed its direction in view of the digital?

The book consists of a series of independent but connected longer aphorisms, of which here I present four.

AB-NORMALITIES, OR WHEN THE EXCEPTIONS ARE MORE CONSISTENT THAN THE RULE

AB-NORMALITIES, OR WHEN THE EXCEPTIONS ARE MORE CONSISTENT THAN THE RULE

In the age of the algorithm, misfortunes that were once accidental have become substantial. In the most diverse fields, we observe anomalies that have mutated to become (ab-)normal which bring a proper measure of instability to cybernetic systems (including those of social control) that were once famed for their ability to create order.

This goes well beyond the idea of the “glitch” as a mode of accelerated production, celebrated in Silicon Valley circles under the motto “Move fast and break things.” As Jussi Parikka and Tony D. Sampson write, “In practice, the programs written by hackers, spammers, virus writers, and those pornographers intent on redirecting our browsers to their content, have problematised the intended functionality and deployment of cybernetic systems.1 ” If up to 40 percent of all the e-mails we are now bombarded with are spam —bringing with them pornographic content, viruses, etc.— then, we can hardly speak here of anomalies (in the sense of more or less insignificant deviations from the norm). Dealing with spam —setting up mail filters, employing virus scanners, activating pop-up ad blockers, etc.— has become a “normal” part of using the internet, an ab-normality.

Just as spam and computer viruses are part of our everyday digital life, we must also understand the high-frequency derivative economy —which operates under the paradigm of the digital— in terms of its “glitches” (just as we must understand our politics in terms of the supposed anomaly of the refugee). We are dealing here not with black sheep or Nassim Taleb’s black swans, i.e. not with more or less improbable extreme events, but with what the volatility trader and market metaphysician Elie Ayache, in his book The Blank Swan: The End of Probability,2 describes as a new normality. Ab-normality.

THEOLOGY OF DEMATERIALIZATION

There is no thinking outside metaphysics, no non-metaphysical thought. Instead there is a lot of bad or imprecise philosophical thinking, not only from professional academic philosophers, but also and especially, wherever metaphysical categories remain implicit and unreflected upon. As an example of the later, consider the many debates over digital technologies, which even in their choice of terminology betray suspicious metaphysical presuppositions. “Network” and, even more, “cloud” are two such deceptive or ideological concepts that obscure the material basis of all computation. N. Katherine Hayles has written a book about “how information lost its body” (How We Became Posthuman),3 and Ed Finn has noted that: “The fact that algorithms must always be implemented to be used is actually their most significant feature. By occupying and defining that awkward middle ground, algorithms and their human collaborators enact new roles as culture machines that unite ideology and practice, pure mathematics and impure humanity, logic and desire.”4

All too often, however, the material platforms and materials used are concealed, as though there were such a thing as pure software without hardware. A compulsion to repeat antiquated metaphysical dualisms, not least that of form vs. matter or mind vs. matter, can be observed wherever the current state of technology is not accompanied by an appropriate level of philosophical reflection. We know the tendency in philosophy to eliminate anything material —there is of course also the reverse exclusion mechanism, with hardened materialists ruling out the significance of any and all immaterial or mental components— as “idealism,” beginning with Plato, but especially with the Neo-platonic (such as Plotinus), for whom all life (including material life) results from mental ideas. And today, numerous ideologues of the algo-cathedral (Ian Bogost),5 whose spiritual fervour (for data) is scarcely less intense than that of medieval theologians, are repeating the very same idealistic symptoms without knowing it.

“Overlooking” the material aspects of new technology is especially convenient for those who profit from the underlying material relations of power and exploitation. (The clearest objection comes from Friedrich Kittler, who several decades ago declared that there is no software.)6 What was true centuries ago —in the ancient slaveholder society of Athens or in the religious Middle Ages— remains true in the age of neo-feudalistic monopoly capitalism under Google, Facebook, Amazon, & co.: our ignorance with respect to the material foundations of the “cloud” or to what is misguidedly called immaterial labor, not only burdens every individual, but affects our society as a whole. Digital platforms, too, are only possible qua the exploitation of material resources: of nature (silicon for microchips, cobalt for lithium-ion batteries, etc.), of the physis of the people who dismantle, assemble, and install them, and finally of all those who use and consume them.

“Overlooking” the material aspects of new technology is especially convenient for those who profit from the underlying material relations of power and exploitation. (The clearest objection comes from Friedrich Kittler, who several decades ago declared that there is no software.)6 What was true centuries ago —in the ancient slaveholder society of Athens or in the religious Middle Ages— remains true in the age of neo-feudalistic monopoly capitalism under Google, Facebook, Amazon, & co.: our ignorance with respect to the material foundations of the “cloud” or to what is misguidedly called immaterial labor, not only burdens every individual, but affects our society as a whole. Digital platforms, too, are only possible qua the exploitation of material resources: of nature (silicon for microchips, cobalt for lithium-ion batteries, etc.), of the physis of the people who dismantle, assemble, and install them, and finally of all those who use and consume them.

The ideology of immateriality or dematerialisation is armchair philosophy in the service of those who currently rule. Here, as everywhere else, there is a connection between what is metaphysically wrong and what is politically wrong. Bad metaphysics always serves bad politics.

GOOGLE NOW TOMORROW

Time is money, goes the motto of money-minded modernity. Just-in-time production and delivery are the dreams of an industrial modernity that reacts immediately and exclusively to demand. Where the production of objects or goods is no longer concerned, as in the speculative finance industry, high-frequency traders spend billions for minimal time advantages, an edge of a few milliseconds made possible by high-speed fibreglass cable connections. And has not the company that epitomises the new digital economy cemented this fixation on ever shorter presents in the very title of one of its most advanced applications, Google Now?

With its AdSense program and accompanying algorithm, Google has achieved what Ed Finn aptly refers to as “commoditizing the contemporary.”7 The aim is to present us with the most precise and promising possible ads in our here and now using data obtained from us in the past (interests, preferences, locations, etc.). Standing behind this focus on the now, however, is no longer the present, but the very near future, a perverted version of what J.G. Ballard once promoted as science fiction for the next five minutes. Google Now “promises to organise not just the present but the near future temporalities of its users. It will suggest when to leave for the next meeting, factoring in traffic, creating an intimate, personal reminder system arbitraging public and private data.”

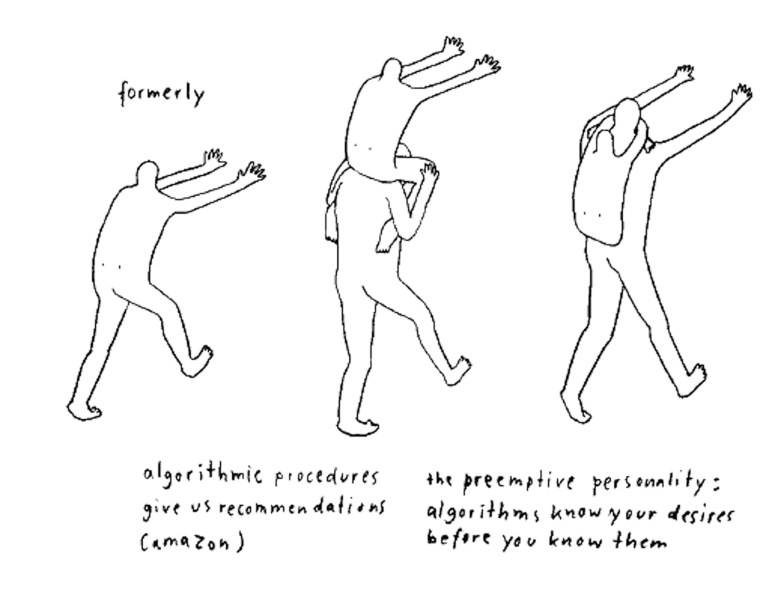

If we follow the title of Finn’s book8 and ask “what algorithms want,” the answer is nothing other than what Google assumes to be our secret desire, namely to help us finally be able to not have to constantly decide (about) the present here and now. Algorithms have since “cross[ed] the threshold from prediction to determination, from modelling to building cultural structures.”

It is only a small step from prediction to restriction. Or in the words of Google Now (and ever?): “The right information at just the right time. See helpful cards with information that you need throughout your day, before you even ask.”

PREDICTION – PREVENTION – PREEMPTION

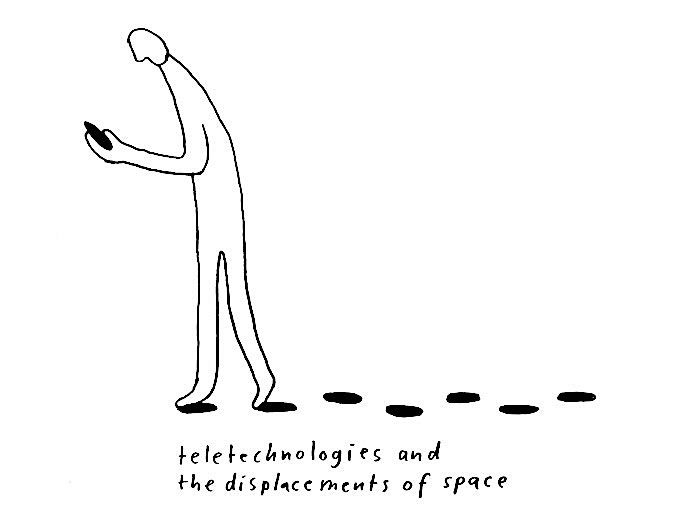

It is high time to distinguish historic forms of control (i.e. efforts to control the future) from those digital ones that we encounter in the present and from the future. The question can be rendered in grammatical terms as the alternative between understanding “control of the future” as a subjective genitive or as an objective genitive phrase, that is: whether we will control the future or whether the future will control us.

From the past, we are familiar with the concept of prediction as prophesying what will happen, i.e. a basically neutral view from the present concerning a future that must be adapted to. Prevention is more clearly determinate and at the same time more negative. Here a negative assessment and the will to avert what is to come go hand in hand. If we fear bad things will happen in the future, then we must change them or not allow them to occur in the first place.

Preemption—which is precisely the opposite of preventive avoidance of a negative prophecy, although the two are often confused—follows yet another temporal logic. This small, largely overlooked difference can be seen with respect to the most well-known form of the preemptive, and the first to emerge into general consciousness. The preemptive warfare waged and first elevated to a state of ab-normality by the George W. Bush administration, contrary to the official rhetoric of prevention, has led not to peace, but rather precisely to the prophesied situation that it promised to prophylactically avoid. Or, to modify a quote from Karl Kraus on psychoanalysis: The “war on terror” is the political illness for which it regards itself as a cure.

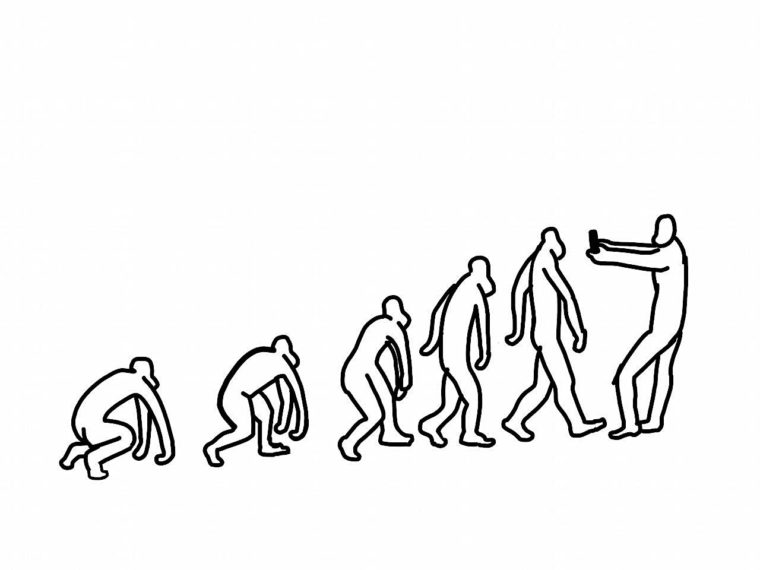

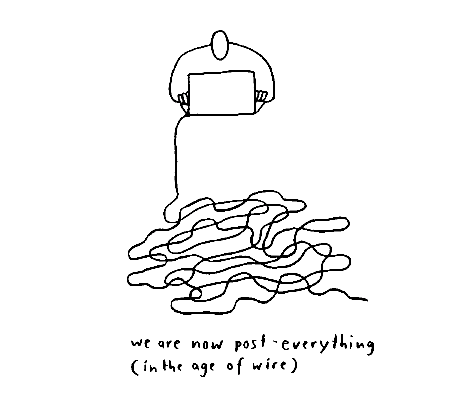

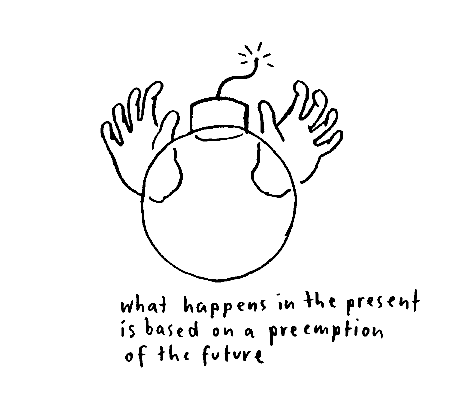

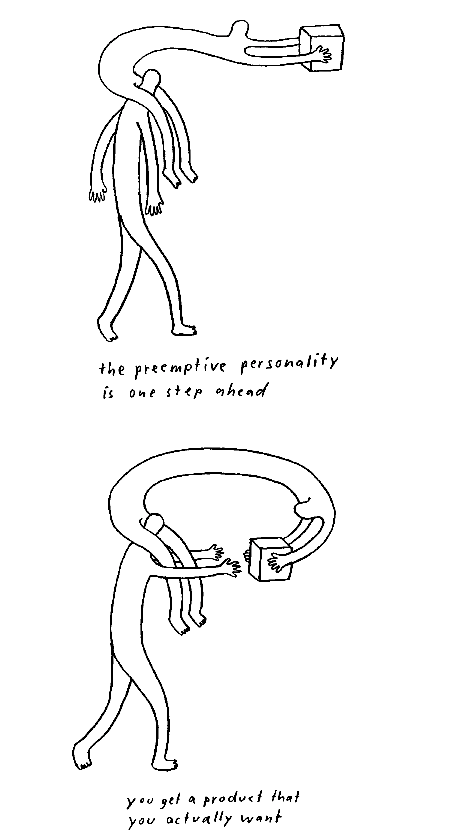

All Drawings are from illustrator and visual essayist Andreas Töpfer from which long lasting collaboration with Avanessian lead to the book Speculative Drawing (Ed. Paradiso, 2018) to wich these images belong to.

1Parikka, Jussi; D. Sampson, Tony. “ON ANOMALOUS OBJECTS OF DIGITAL CULTURE. An Introduction.” Academia.edu, 2015. Available online here.

2 Ayache, Elie (2010). The Blank Swan: The End of Probability. New Jersey: Wiley.

3 Hayles, N. Katherine (1999).How We Became Posthuman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

4Finn, Ed (2017).What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

5Bogost, Ian. “The Cathedral of Computation.” The Atlantic, 2015. Available online here.

6Kittler, Friedrich. “There is No Software”. Ctheory, 1995. Available online here.

7Ed Finn, op. cit.

8Ibid.

Armen Avanessian was born in Vienna. He defines himself as a speech strategist, a publication activist and a platform creator. Based in Berlin, he trained in philosophy, literary theory and political sciences in Vienna, Bielefeld and in Paris with Jacques Rancière. He is a professor at several European and American universities. A founder of the bilingual research platform Spekulative Poetik, since 2014 he has been editor at Merve publishing house in Berlin. In 2017 he began to host a successful series of events under the name Armen Avanessian & Enemies at Volkbühne Berlin. He is a prolific writer, and has over a dozen books published, some of which have been translated into Spanish; Miamification and Realismo Especulativo will be out in May 2019, published by Materia Oscura, and Aceleracionismo published by Caja Negra (Buenos Aires). Also in English are Metanoia (Bloomsbury) and Irony and the Logic of Modernity (De Gruyter), to mention a few.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)