Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Didier Fassin is an anthropologist who, among other topics, studies police. In one of his field studies, Didier interviewed a police commissioner about the racial persecution of youth in Paris suburbs. The police commissioner, with a smile on his face, told Didier that when a police car arrives, young people start running without even knowing why. The police officers often manage to arrest them but when they are questioned in the police station, it turns out that they did nothing illegal. “Then why did you run?” the police ask the kids. They have no idea, and either don’t respond or say they don’t know. The police commissioner cleverly suggests to the anthropologist that it must be a Pavlovian reflex.

In such a situation, we would all like to respond as Fassin did, that “the fact that the police start chasing them when they see them running must respond to the same type of reflex.” It is unlikely, however, that we have so many reflexes. This small scenario, common also in our streets, can give us a glimpse of a reality ignored by the police, what I propose to call poorly communicated places. I said “ignored by the police” since to ignore it is to assume the position of the police, even if one believes they are not doing so. In such places, the suspect does not know or does not respond because any answer they might give would only be miscommunicated. Police interpret their responses by using cheap psychology and a pinch of dehumanization, and the end result is violence, arguments and everyone going home.

What happens then in this encounter, as aleatory as it is politically programmed? What are these places? In reality, they are the opposite of those places dreamed of by capitalism that, in a sense, also turn out to be poorly communicated. I refer to the aesthetics of private, exclusive places, not at all democratic or popular, to which one only goes by paying a high cost in time, money and knowledge. One must know where they are to get to them and one must pay to enter them. These are holes in the networks of movement: without trains or buses or roads. It’s not that they lack infrastructure, but rather that they are lavishly planned holes. Just as the nodes of productivity that the infrastructures support are not neutral, neither is the exclusivity generated by the absence of accesses. But no, these are not the poorly communicated places inhabited by young people previously detained by the police. These private islands or mountain shelters dreamed up by capitalism can be considered places of incommunication, where people need not justify their presence and can enjoy a sanctuary of relief in the era of mass communication.

The poorly communicated places that interest us, however, often overlap with the neglect of the Department of Public Works but are not limited to them. They are not defined only by their accessibility but also by certain power relations that produce a certain type of subjectivity. The precariousness of the means of transportation is for these spaces only one more vector in the production of individuals. As if it were a malicious metaphor halfway between the engineering of bridges and roads and studies of subordination, these spaces require discomfort to reach them and, above all, they make it impossible to speak from them. To understand these spaces, the key question we must ask ourselves is, to paraphrase the thinker Gayatri Spivak, “can they even talk?” That is, can they be assumed as subjects of enunciation? There was a famous debate within the Stalinist USSR about whether language was superstructure or infrastructure in the Marxist sense of the term. The question was to know if the language and the way in which the workers expressed themselves was something consubstantial to class consciousness or just an accessory. Today we should ask ourselves the same thing though not about actual spoken languages, but rather about the capacity to become the subject of an enunciation. Is the ability to speak for oneself superstructural and therefore accidental, or is it rather a network of powers found within bodies and territories? Or better yet: could Fassin’s young men stand still and claim they weren’t doing anything wrong?

In the field of psychotherapy, of which I am a devoted critic, it is often considered that the ability to speak for oneself depends on individual merits. If you can’t speak it is because you lack the symbolic resources, the guts or the self-confidence that would allow you to do so and which psychological practice can help provide to people. In reality, such a thought is equivalent to the depoliticization of places of enunciation. In practice, this reveals us to be accomplices of hegemony when the poorly communicated places speak for themselves and are always judged as a provincial dialect, babble, in emotional turmoil or speaking only the little that they possesses: their subordinate experience. All possible communication is part of the register of miscommunication and loss of meaning. Like our police commissioner, who considered their running a reflex rather than an act of reflection, hegemony not only subordinates the territory of the habitable but also of language. The periphery, not necessarily in a geographical sense, is not only poorly communicated in relation to the transport network but also in the network of meanings, as well.

The opposition that Michel Foucault gave us between utopias and heterotopias fits into these considerations. Foucault explains how, although utopian places would be those that are nowhere except in the mind of man, heterotopic places do exist but, historically, we have turned them into spaces of exclusion. According to Foucault, in the past these would have been welcoming spaces located outside of society. These places are where subjects in crisis would stay, that is, those whose identities and practices are not sustained by hegemony and, consequently, whose capacity to establish themselves as a subject of enunciation would be questioned. We have converted the reception spaces of these subjects, such as the initiation rites for adolescents, the homes for menstruating women or shamanic trance spaces, into devices that exclude such discomforts from so-called normality: menstruation management technologies to help deny it, the pharmacologization of psychic excesses or, as the police commissioner showed us before, the ghettoization of social conflict. In each of these heterotopias the subject can only respond through the meanings of their exclusion, that is, poor communication and the inability to speak for themself is what defines them as spaces. Thus, with police patrols, young people can only become subjects through the meanings that exclude them and by corroborating the police commissioner’s intuition, even when these are wrong.

Likewise, such a difference is productive for thinking about corporeality and discourses. We can speak of utopian bodies, which do not exist but which we all know and which determine all of us (even if only through anguish). There are heterotopic bodies that are excluded from representativeness and even habitability. There are also utopian discourses, such as in science, with that which is poorly communicated excluded from its formalization, and, on the contrary, there are also heterotopics, such as sex-dissidents or Black Lives Matters, that is, who assume their politicization as the subversion of the subject that sustains them.

The fact of inhabiting a poorly communicated place is inscribed, thus, in the unequal distribution of territory, but also in the unequal distribution of the ability to create meaning. Provincialism and periphery produced by cuts in the territory are also cuts within meanings that can be expressed. Perhaps in this way it can be seen how psychoanalysis understands speaking as making a cut in a surface: speaking for oneself not only leaves a mark, but also affects the redistribution of space. There is no heroism there, there are no geographers who can redefine the entire territoriality, only micropolitics of cuts and resistance. Avoiding being ignorant of our own “Pavlovian reflections” (like the police who chase young people) necessarily implies looking for the poorly communicated places that inhabit us.

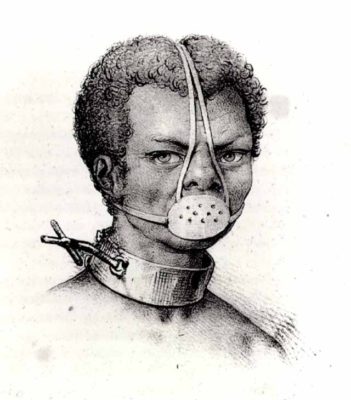

(Featured Image: Jacques Arago “Escrava Anastacia” 1839)

Miquel À. Riera is a bookseller and psychoanalyst. He investigates the subversive possibilities of analytical practice when it is influenced by contemporary critical thought.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)