Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

On the 1st of March 2020, the 39th edition of ARCOmadrid held its closing day at the Ifema fairgrounds. It had been an unusual edition because of the news coming from Italy, where a strange illness arrived from China was causing infections and deaths. It became the main conversation topic during that short week the fair lasts. Mostly, ironic comments about Italians, as we all know, and jokes about the odd weirdo who, in the early days, dared to wear a face mask. Generally, we all greeted, kissed, and hugged each other when welcoming guests to our stands, just as we always had.

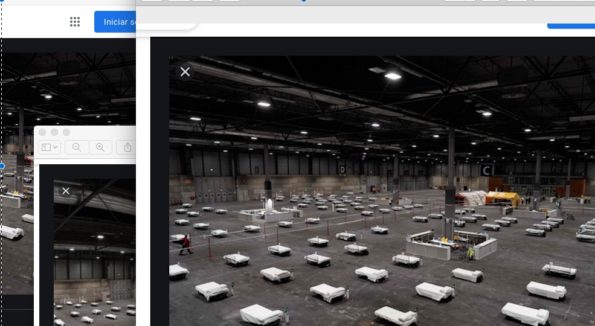

A mere 15 days later, a nationwide lockdown was declared by the time the country was overtaking Italy in infection cases. Shut away in our homes, in sorrow and fear, amid an unfamiliar silence in the city, we knew about the outside world only through the media. And that’s how, in all national press outlets, we saw the photograph of the field hospital set up at Ifema on the 23rd of March. In little over 20 days, the pavilion went from hosting the art fair we had known for 40 years to producing a frightful picture that looked like something out of a dystopian film.

“Spain’s biggest hospital” was the most repeated phrase. “Built in record time”. First at pavilion 5 and then pavilions 7 and 9. That is, precisely the ones where ARCO’s regular or larger editions had been regularly hosted. 1300 beds, 100 ICU jobs, and all of it upgradeable if ever required. Spaniards were proving our organisational skills to turn reality on its head and set up a hospital in a place that until recently had hosted contemporary art. The same thing we had seen the Chinese do, the month prior, from our sense of superiority (obviously, back when that illness remained other people’s problem, that couldn’t possibly happen to us). Suddenly, we too were facing the dread of an almost 10,000 square metres and over 10 metres high venue being filled with beds.

Ifema was a justified choice for obvious reasons: the existence of an available empty building; a location integrated with a communications system, the functional possibilities of pavilions. 7 and 9 were thus favoured over the others because they boast underground cable ducts that make it possible to drive oxygen to all beds. An initially practical fact that suddenly became brimming with the horror that it implied. Then it came back to our minds that Ifema had already been used at other times to provide emergency services: when it was host to the retrieved corpses of the Spanair air crash and the victims of the 11-M terrorist attacks.

Concurrent with this picture, a wartime rhetoric came along: a battle against the virus, field hospital, combat strategy. What was happening to us was no longer our ordinary life. It became that which precedes normality, which is neither what life was like before nor what we were used to. In exceptional times, language sheds its ordinary usages to take on new meanings, but our memory of that previous usage (connecting then with now) is what makes us aware of the exceptionality we are living through.

The type of structure Ifema belongs to is the iconic creation of the Modern Movement architecture. It is the so-called “box”: a basic building, apparently refined thanks to the use of concrete and steel, without decorative features that associate it with one single given role and, therefore, adjustable to any end. Simplicity in form, infinite uses. They are a result and a symbol of modernity. Accordingly, it is unsurprising that the same building can serve (late-capitalist architectural nightmares aside) as a sports centre or a library; as an airport or a theatre. As a fairground or a hospital. An urban myth claims that the Faculty of Information Science building was initially envisioned as a prison.

Rosalind Krauss wrote that the grid is the basic structure of 20th-century art. To the art critic, this pattern “announces […] modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to […] narrative […], it turns its back on nature”. It is “antinatural, antimimetic, antireal”. “In the flatness that results from its coordinates, the grid is the means of crowding out the dimensions of the real […]” (R. Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modern Myths, 1986). In consequence, it comes as no surprise that such an array of beds reminded us of a work of art at once. It could almost be a performance by some artist who had taken part in the fair. A special project. One of those ARCO events that still makes the headlines. The sort of piece discussed for its price tag, or one that gets people asking how can it even be sold (sheet music? Instructions on paper?). One that will be confidently dismissed as not art. The same could apply to many pictures appearing in the media at the time. I especially remember a row of oxygen canisters, disturbingly arranged.

Terror results sometimes from uniting two images that shouldn’t be together. Javier Marías describes this in All Souls, when the character Alan Marriott, a cripple, talks about his dog, which has an amputated leg, and how, in its company, he doesn’t stand out as he would when walking beside a perfectly healthy girl. Horror, he says, depends “to a large extent on idea association. On conjoining ideas. On the ability to unite them. You can never link two ideas so that they show you their horror, the horror of each one of them, so you never get to know it in your life. But you can also live in fear if you have the misfortune of linking the right ideas all the time. For instance, that girl selling flowers in front of her house. There is nothing terrible about her, she can’t instil horror on her own. On the contrary. She looks really attractive. She is nice and kind… But that girl could instil horror. The idea of that girl, linked with another idea can instil horror. You don’t believe it? We still don’t know what is the missing idea, the right idea to instil horror in us.

Joaquín García Martín, born in Madrid, the city where he still lives and where he did his higher education, has collaborated in management tasks with a large number of local institutions dedicated to contemporary art in. After years of managing someone else’s gallery, he decided to open his own gallery in spite of everything. For 8 years, he made it the place where he gave rise to the artistic practices he believed in until reality and the pandemic forced him to be more realistic. Recently, he has decided to channel his professional practice through writing and curating. In both sectors he advocates research and dissemination of the other realities existing beyond the hegemonic centres of thought, economy, visibility and ways of doing.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)