Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

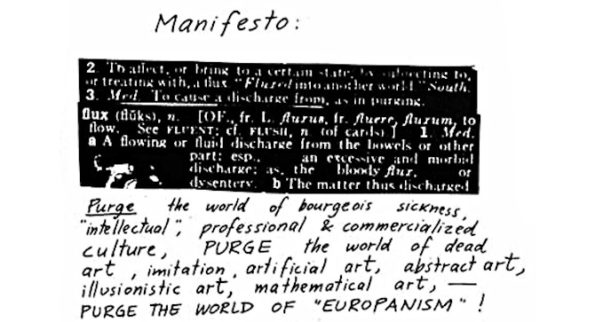

How do the changes that precede revolutions arise? What is the silence like prior to the big event? Who intuitively guessed at the potential of the new technologies? And the possibility of renewing already classic languages? What is important about the show +- 1961 Founding the Expanded Arts is that it inhabits a niche with the answers to all these questions.

The exhibition can be seen from now until the end of October at the Museo Nacional Reina Sofía (MNCARS) in Madrid. It is one of those necessary revisions of key historic moments, when timid advances ended up being eclipsed shortly afterwards by the joint explosion of various events. It’s not that nobody is unfamiliar with the work of John Cage or Dick Manfield but this is undoubtedly a loquacious exhibition about their exploration of the limits of music. Their scores, accompanied by all sorts of additional documentation, are shown as collateral products of a negotiation or joint investigation, shared, and debated by the members of a small community with common interests.

We also already knew about the importance of dance in the development of new artistic languages in the last forty years of the 20th century, about the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop, about Ann Halprin and her insistence on improvisation. About how important it was to call oneself mover instead of performer and, above all, of accepting the event for what it was, of understanding it as something in itself, that couldn’t be rehearsed, absolutely contingent and different. We knew that Robert Morris had been there long before he called himself a sculptor.

And in theatre. That George Brecht thought of his musical compositions as related to objects, that he moved from calling them music to calling them events. That his companion Cage, once again, would talk of theatre as “the constant situation where you can see, here and smell things”. We knew about the imprint left by the theatrical script, in the form of instructions, as a limit for everyone else.

We’d read that Yoko Ono’s loft was the scenario for all this. That Maciunas’ AG Gallery organised exhibitions for all of them. That they were a group of friends who did things just for themselves. It’s said that they and the following generation didn’t know each other. Apparently there was no contact between the fluxus, the minimal and the conceptual. However strange that might seem, given they were all living in the same island.

The show is a fundamental reading of how they all launch themselves into the search for contingent silence. It describes what happened before the huge explosion at the end of the decade. It is framed within this genealogy of the arts marked by the emphasis on the imprint that the scenic arts have had on contemporary thought; which defends that the liberation from the ties of the plastic genres was seen with a core acceptance of questions more familiar to those who work with the body and the senses. This summer the MNCARS gives an excellent lesson in the history of art.

Paloma Checa-Gismero is Assistant Professor at San Diego State University and Candidate to Ph.D. in Art History, Criticism and Theory at the University of California San Diego. A historian of universal and Latin American contemporary art, she studies the encounters between local aesthetics and global standards. Recent academic publications include ‘Realism in the Work of Maria Thereza Alves’, Afterall, autumn/winter 2017, and ‘Global Contemporary Art Tourism: Engaging with Cuban Authenticity Through the Bienal de La Habana’, in Tourism Planning & Development, vol. 15, 3, 2017. Since 2014 Paloma is a member of the editorial collective of FIELD journal.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)