Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The Latin word for box or chest is arca, from which “ark” is derived, as in Noah’s Ark. The Ark provided a safe haven, but Noah had to impose strict screening conditions for entry: only two animals of each species were allowed on board. In this respect, Noah’s Ark is a microcosm of the world in general, since the smaller the space, the more limited and therefore the more valuable the content.[1]Assmann, Aleida. (2011). Cultural memory and Western civilization. New York: Cambridge University Press

In a museum’s ark or archive, many species coexist: conservators, curators, those who work in the exhibition department, researchers and communication experts, all of whom, without a doubt, would be saved from the flood. However, museum educators would perish underwater because, in the microcosm of the museum, education survives in a subordinate or subaltern position and whatever is outside the archive perishes in the flood.

The species that are saved from the flood have historical tools that allow them to float: there is always a visual or written record of acquisitions, expensive exhibition catalogs, and a special presence on social media. At any time, within any museum, we can re-visit an exhibition that took place ten years ago and see each piece in the collection. It is practically impossible, however, (as the reader can see for themselves) to rescue any project from more than three years ago developed by any education department from any museum.

The institutional archives of museums store everything related to their collections, exhibitions, acquisitions, store, and even their cafeteria. Institutional archives, however, do not house a neutral history of the museum, which reveals its priorities. Namely, what is worth keeping and what makes up institutional memory? The absence of education in institutional archives suggests that, although museums are founded as educational institutions, the museum’s priorities very well might be quite different.

The reality is that the education departments of museum do not record, do not remember, and do not store anything in archives. It is almost impossible to follow the trail, to know what happened, and who did what and when. This situation exists, among other reasons, due to the condition of subalternity in which we still find ourselves, a situation that Preciado points out in the following text:

What is the complex relationship of hierarchy or even political rivalry between the exhibition space and what is commonly called “the activities” or the public program, or what Belén Sola called “mediation?” I am referring to that set of programs that have been placed in a subaltern or marginal position within the museum institution, which appear as a footnote to the exhibition or collection, or as a supplementary element that supposedly serves to attract new audiences and to establish a better relationship with the social context of the city in which the institution exists… [2]Preciado, Paul B. (2019). “Cuando los subalternos entran en el museo: desobediencia epistémica y crítica institucional” (When Subordinates Enter the Museum: Epistemic Disobedience and … Continue reading

If the condition of the subalternity of education departments prevents us from storing in an archive, filling the ark with the rest of the museum species and under the same conditions, undoing this condition involves understanding the archive as a tool for institutional struggle.

Creating an archive gives rise to the subversive idea that education does not produce events and activities, but rather is a process of intellectual production that honors the museum’s founding mission. Undoing the subalternity of the education departments requires an assault on the archive, reclaiming the central place of the public and its learning in the heart of the museum, and addressing three lines of action that include reflexivity, the processes of collecting and the destination of time and money.

Dissolving the doing/thinking bipolarity becomes, in our case, the making visible of what we think, as developing transformative educational practices can only be done from an embodied reflexivity that generates meaningful programs, related to problems that reconcile institutions with social honesty, and which make the idea of the public museum as a mechanism of social compensation a reality.

Making visible the thought processes that are already taking place in the education departments could be the first step to formulating a position and, from there, a need for archives.

Educational activities in museums are performative and temporary, they cannot be made into visual products, as artists do, nor into tours or texts, as curators and conservators do. Participants take their presence with them, embodied in personal memories and volatile, mental, and therefore non-transcendental narratives.

Generating collection processes of this oral process by creating texts, producing podcasts, videos, and photographs is necessary, but we believe we must go further than that. We want to embrace the “contradictions, inconsistencies and banalities”[3]Guasch, Ana María. (2010). Arte y archivo, 1920-2010: Genealogías, tipologías y discontinuidades (Art and Archive, 1920-2010:

Genealogies, Typologies and Discontinuities), Akal, p.45 of the stories of education in museums through formats such as diaries, graphic and narrative documents, and video formats, in order to investigate formats that go beyond the clean and antiseptic institutional discourse in order to address documentation that speaks of what is excluded in these stories.

Images, therefore, form the only lasting visibility, the “only proof that something happened.” These play an important role in the economic reproduction and legitimization of educational programs in museums, as they serve applications for funding as evidence of their social and educational effects. Until now, there has been little discourse about the universal and universalizing narratives these images create.[4]Mörsch, Carmen. (2006). “Application: proposal for a youth project dealing with youth visibility in the galleries”. En A. Harding, Magic Moments: Collaborations Between Artists And Young People … Continue reading

To fill the ark with objects we need to allocate what is most valuable, that is, to find time and material resources, to reserve part of the time we dedicate to programming and implementing to reflect and record. It should be policy that education professionals, just like curators and artists, dedicate part of their time to writing, reading, and to generating spaces to produce lines of thought in which, as Luis Camnitzer says, one may carry out one of the most important missions of the museum institution, that is, to transform the spectator.

In writing this text, we realize that it is not that there is no ark, but simply that it is not where it needs to be.

Indeed, we must look for it, clean it up, and give it value.

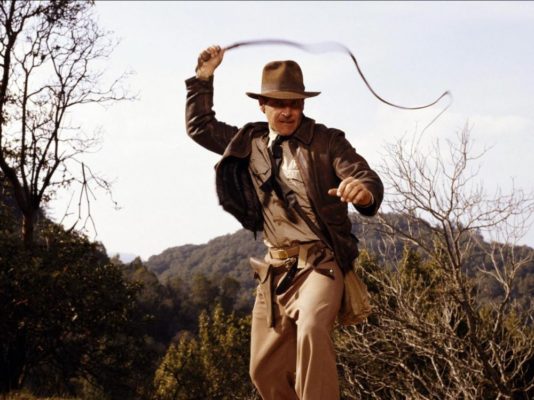

We want to reverse what Indiana Jones, through his very colonialist and macho saga, showed the world about archives. We, from our decolonial and feminist position, do not want to create a new ark, but rather to recover the lost ark.

From 2022 onwards the project “Mediating the Future” will take place, in which the artist Begoña Solís, together with the team of the Museo Reina Sofía’s Education Department, will open a line of research focused on visual archives in Education Departments. This photo is one of the first records of the aforementioned project.

| ↑1 | Assmann, Aleida. (2011). Cultural memory and Western civilization. New York: Cambridge University Press |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Preciado, Paul B. (2019). “Cuando los subalternos entran en el museo: desobediencia epistémica y crítica institucional” (When Subordinates Enter the Museum: Epistemic Disobedience and Institutional Criticism) in Belén Sola (Ed.). La educación en museos como producción cultural crítica (Museum Education as Critical Cultural Production) Catarata |

| ↑3 | Guasch, Ana María. (2010). Arte y archivo, 1920-2010: Genealogías, tipologías y discontinuidades (Art and Archive, 1920-2010: Genealogies, Typologies and Discontinuities), Akal, p.45 |

| ↑4 | Mörsch, Carmen. (2006). “Application: proposal for a youth project dealing with youth visibility in the galleries”. En A. Harding, Magic Moments: Collaborations Between Artists And Young People (1st ed.). London: Black Dog Publishing. |

María Acaso is a cultural producer whose projects focus on challenging the divisions between art and education, the academic and the popular, theory and practice; on developing contemporary education and transforming the formats of knowledge transmission. A founding member of the collective Pedagogías Invisibles, she is currently Head of the Education Department of the Reina Sofia Museum.

Sara Torres-Vega teaches artistic creation and education in the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Complutense University of Madrid and at New York University. She researches Education departments, archives, and activities in museums (Tate in London, MOMA in New York, and the Reina Sofía in Madrid, among others). As an artist, scholar and educator, she focuses on relational and participatory practices that highlight art as a catalyst for inclusion and social connectivity. www.saratorresvega.org

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)