Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Maite Muñoz – Ever since I can remember I’ve had a slight tendency to OCD, the disorder that – among many other ludicrous things – makes you obsessively align objects on your desk several times a day, or invariably underline books with a ruler. The more or less metaphorical connection between this persistent distress and archiving was discussed some time ago by Jorge Blasco.[1] Leaving personality traits to one side, today I still wonder how I got into this archival thing, what it is about archives that fascinates me (and sometimes also repels me). The fact is that the archive is a trending topic in the field of culture in general, and in that of contemporary art in particular, as corroborated by the attempts to establish the genealogy of this phenomenon, the multiple theoretical approaches to it and the proliferation of seminars and brainy encounters dedicated to the subject. The legacy of postmodernism, the crisis of the notion of the institutional archive, especially in connection with colonialism, and the numerous tentative proposals and successive attempts at creating alternative memories have put the word archive in everybody’s mouth. Before this panorama of popularity, despite my admiration for this part of creation that remains on the margins and moves gracefully through documentation centres, archives and libraries, I’m starting to have misgivings. Could our construction of another hegemonic discourse actually be defusing the power of the archive? Or is it simply a fear of seeing the archive temporarily become the queen of the ball, and of people no longer looking at me oddly when I tell them that I’m into archives?

I try to think of all these things from my present position: after eight years as a member of the team working at the Study and Documentation Centre at MACBA, where I learnt the rudiments of archives in institutional settings and had the privilege of witnessing a project from its tender beginning, I now find myself in the quicksand of freelancing. This new phase has enabled me to become involved in independent archival projects such as those of the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive, the Guatemaltan YAXS Foundation or the Muntadas Archive — extremely different geographic, social, political, economic and cultural spheres, with the richness of perspectives and opening up of new worlds that this speciality furnishes.

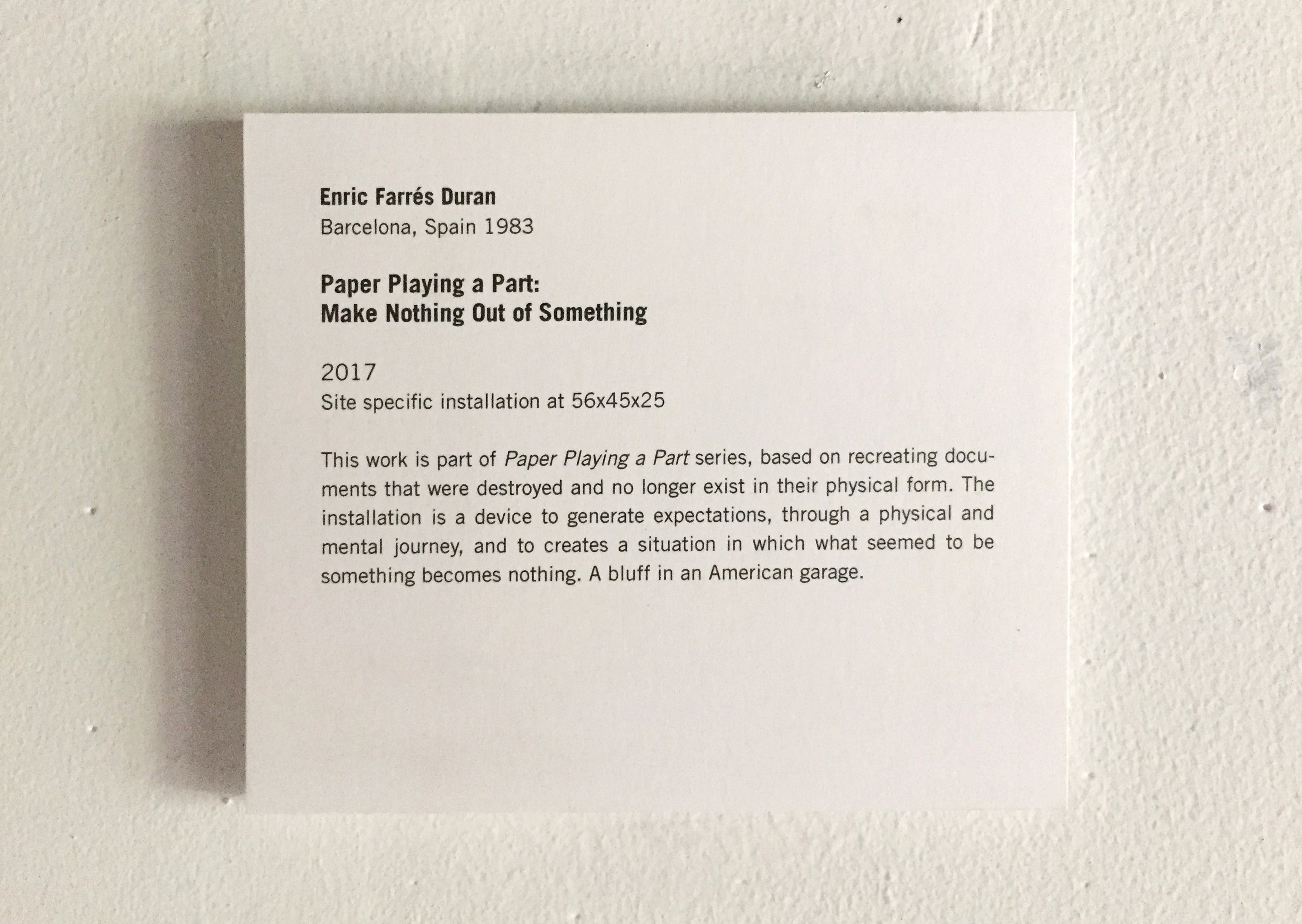

And then we have Vista Oral, that self-managed loss-making collective that brings me so much joy and thanks to which we have enjoyed experimenting with artists, some of whom have approached the archive with a fresh gaze, exploring and exploding its limits, as in the case of Enric Farrés Duran, Antoni Hervàs and Hailey Loman. Also in the context of the collective, probably due to our philias and in order to go with the flow in view of the times, we have worked with archives when researching the phenomenon of rave music, and in the case of proposals for different calls (all unsuccessful, which will soon see the light in a compilation of failures we are currently preparing).

I find all these projects fascinating, because instead of considering the archive a passive receptacle, they view it as an entity around which collaborations, interpretations and activations are generated through open, dialogical processes with different agents. And without further ado, in this ping-pong that is a brief observation on the relevance of critical reflection and practice in the fields of technologies, politics and economies of the archive, I give way to my colleague in arms at Vista Oral, Alicia Escobio.

Label of Realizar un papel (Paper Playing a Part), at the Enric Farrés exhibition in the framework of the INÚTILES (USELESS) series, 55x45x25, 21 April 2017- 21 April 2042

Alicia Escobio – I think that my case is a bit like Enric’s, that I’m aware of the fact that I approach the archive starting from the common research we carry out together. I think that, like him, I began with Leland Palmer in Lo tengo, no lo tengo (I Have It, I Don’t Have It), working on the concept of collection fascinated by an attitude designed to transform an impulse to follow a certain object into a project. But also as a political approximation to the disjunction established in a collection between the process in which an object is produced and its subsequent state of permanence, that questioning of the conceptions of use/disuse, useful/useless that we can extrapolate and connect to concepts such as success and failure in capitalist societies.

It’s true that when I first come into contact with an archive I don’t follow any specific model, nor do I reproduce in detail the conditions of any archive, like Enric does in Establecer un principio de procedencia (Establishing a Point of Departure). In Second Attempt we compiled a great deal of information on censored art projects, also with the Palmer members, which obliged us to find tools that would highlight first-hand testimonials that are multiple, generating debates and not truths. This was when I familiarised myself with the anarchive concept, that was never an end in itself (as you, being a fanzine designer, know well). Considering what we’re doing brings Alex and Paco de Render into the debate, whose work in the field of programming focuses on creating open code tools that work like the most sophisticated repository, which they make available and adapt to all those projects that have something we can explain together.

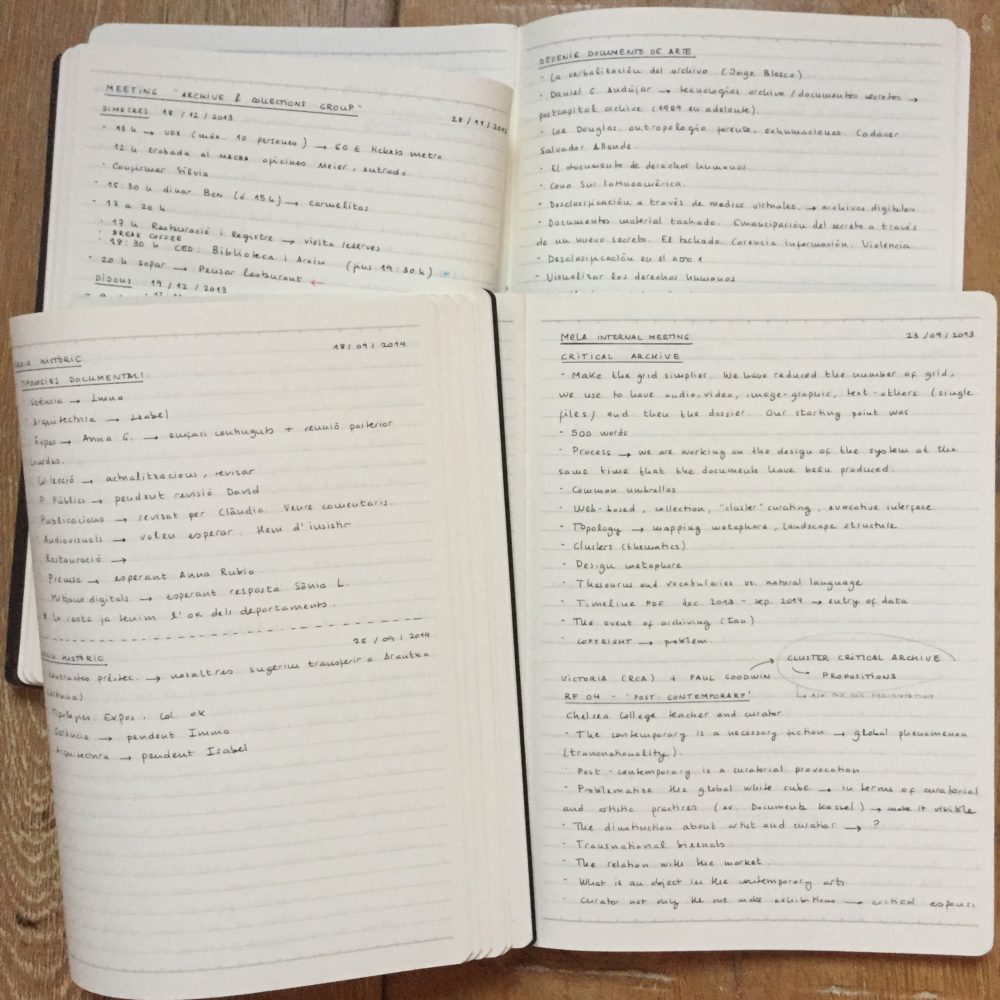

A similar affinity (there is much affection in anarchives) brings us into contact with Ricardo Duque, a member of the Fanzinoteca, Todojunto, L’Automàtica and Dinou. With Ric we feel a political identification that is a way of understanding culture — I’ve never missed a tagging day since! Besides website design support, we create the relevant questions to make sure the organisation of information isn’t hierarchised from the common tools we are constructing. And you yourself of course, because as well as slogging away with us in the field of praxis you also help us construct concepts. I think Vista Oral introduces the questions we both raise into their construction, and for me this is a crucial pedagogical project. Given that you began by speaking of your tendency to OCD, I think we could show your notebook to illustrate this part of the conversation.

Like every self-respecting anarchive, Second Attempt remains unfinished, subject to the fact that there are no motivations more pressing, or with which we currently feel greater affinity. And then there are obligations too, of course.

When we began to work at Vista Oral with Hailey Loman for Koob Gallery, I intuitively thought of how anarchives and institutionalised archives move in an intermediate territory, understanding the particularities of both and stressing their overlappings as well as their oppositions. Her work, that addresses the impossibility of preserving a memory, led her to set up the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (LACA) with other artists and cultural agents Los Angeles, who amateurishly – term derived from the Latin amator, lover – manage a totally functional archive that also forms a part of her work as an artist. A repository that examines and confronts the institution of the archive and tries to preserve the ephemeral nature of the performance, along with artists’ books, exploring the contradictions that exist between contemporaneity and preservation, living art and artefacts. A changing space that attempts to tackle and challenge power relations between the individual and the institution through the transversal roles played by artists and the voluntary workers in the space. A space that also seeks ways of becoming involved in the work of the archive that escape alienation.

Hailey Loman facing everyday management problems at LACA

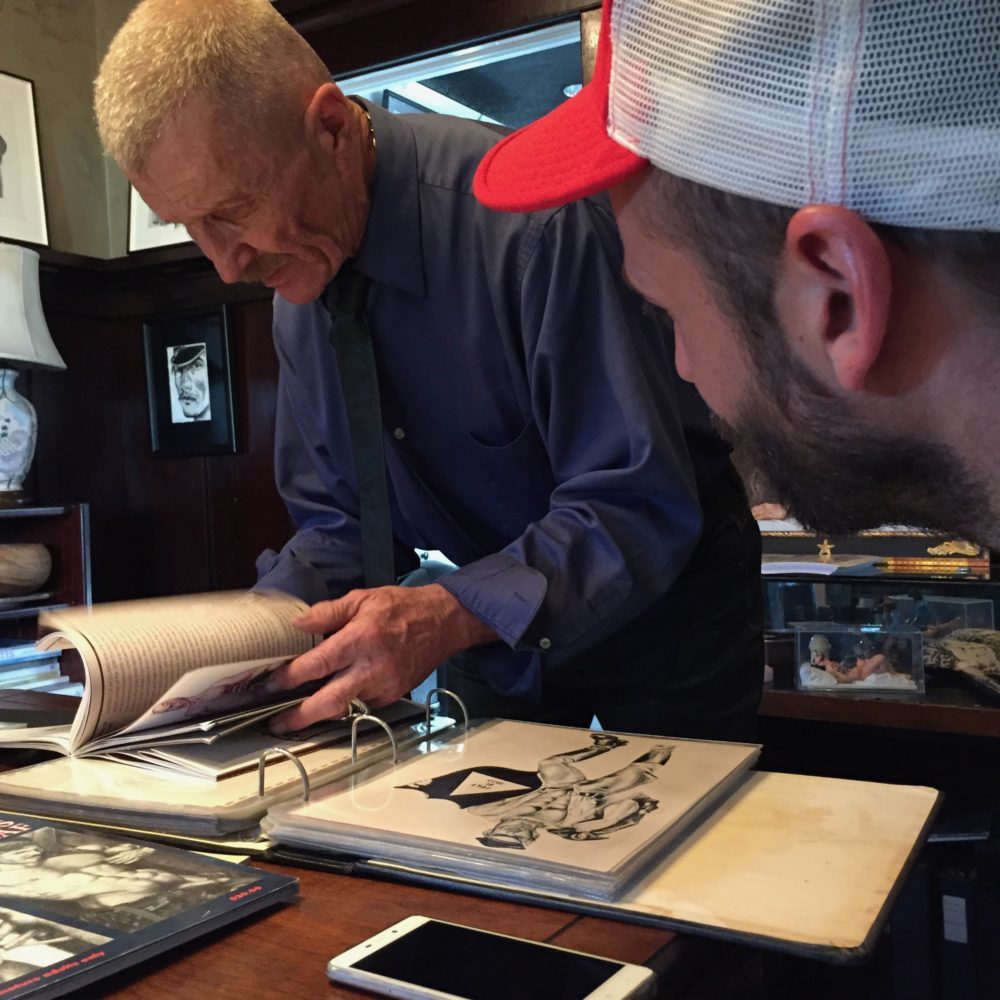

MM – Antoni Hervàs, half medium half troubadour, passionately pries into documents belonging to figures whose practices he analyses and reinterprets from the purest admiration. During his sojourn in Los Angeles we witnessed his unorthodox research into feminine and masculine stereotypes, and how these are called into question through the use of the body in certain amateur or marginal physical practices. In his immersion in the documents on the figure of artist/dancer/choreographer Chuck Arnett that belong to the heritage of ONE Archives, Toni began to explore fist fucking, focusing his attention not so much on the most explicit aspect of the practice as on the codes, symbols and gender clichés associated with it. We also bore witness to the marvellous experience at Tom of Finland’s house archive, where paper documents merged with personal friends of the artist’s, conveyors of oral memory, and with kitchen containers that reveal his particular way of inhabiting the world. In Toni’s case, personal experiences are combined with collective memories, with field studies and with archive research, where the latter is conceived as another figure in his story. The links between body and archive, the performative potentiality of the documents and the notion of the body as a battlefield are expressed by an expanded, elastic and mutant drawing.

Antoni Hervàs totally engrossed in Tom of Finland’s immersive archive

I suppose that, at the end of the day, everything is related to the fact of being composed of contradictions, to the fact that life is a long-distance race in which we are constantly trying to maintain coherence and yet fail. And the same thing happens when we have to contend with what we have called archive, where all critical visions negotiate continuous tensions: between preservation, accessibility and use; between a presumed objectivity and the introduction of collective memories and parallel narratives; between regulations that allow for inter-operability and folksonomies constructed through common experiences that transcend hegemonic thoughts; between the right to memory and the legitimate right to avoid being archived, to prefer not to leave any mark in this age of instantaneous and involuntary recordings.

[1] Jorge Blasco has examined this notion starting from his own experience and his facet as an Amateur Archivist, which culminated in the exhibition entitled TOC: Una colección propia. Obsesividad compulsiva e imagen contemporánea en las Colecciones del MUSAC y el DA2 (OCD: A Personal Collection. Compulsive Obsession and Contemporary Images in the MUSAC and DA2 Collections) held in 2016.

Vista Oral are Alicia Escobio and Maite Muñoz, a collective of curators and researchers. We are interested in failure, uselessness and any political dimension of unproductivity. We approach projects as an apprenticeship in which, together with an artist, we open participatory spaces based on interaction and exchange of tools and micro-narratives that help us to generate a collective critical discourse. In Los Angeles we managed Garaje, and previously we were in charge of the space 56x45x25. Together with Eloi Gimeno, we co-directed the publishing house Folleto until 2019. We are currently part of the international collective continent.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)