Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Let’s start with a fanciful supposition: what if the government decrees by law that all men between 15 and 20 years of age have to be circumcised. It’s obvious that this is inconceivable, on the one hand, because in an obscure and undisputable manner the supposedly laic country in which we live assumes the mandates of the Catholic Church, and a phobia of Islam or Judaism. Secondly because there are very few cases in which the lawmakers, principally men, legislate against themselves if it is not in the form of a common good. That is to say, they can raise taxes so that the state has more resources; but endure physical torture simply because it’s “right”? I’m afraid not.

But let’s carry on playing the impossible and imagine that the law will be passed. There will be furious protest demonstrations, and no doubt there will be many women in these. From mothers anxious about their sons, brides, brothers and worried friends, to women against ablation and defenders of civil rights. It would become patently obvious that the law made no sense, and that the option of being able to take decisions about one’s own body is a universal right that ought to be inalienable.

In contrast, the abortion law has led to the phenomenon that as women we’re more than accustomed to: the famous “this has nothing to do with you”. Standing at the bar, beer in hand, going into a tirade about the bastard Gallardón, that it’s worse than in Franco’s time… many men don’t have a problem in showing their solidarity and commenting amongst colleagues that it’s an unjust law. What they don’t see is that it’s unjust for them. And even more curiously they still struggle to put two and two together and understand that if their girlfriend ends up pregnant by surprise or by accident, they’ll also have to take care of the infant (or ought to). A little kid what’s more that might have spina bifida. But the worst thing is that they have no conception of how the abortion law also infringes their rights as citizens, because it limits the right to choose for oneself, and that in any case, the limitation of the rights of one group of citizens is a limitation of society in general, an impoverishment in any egalitarian political and social system.

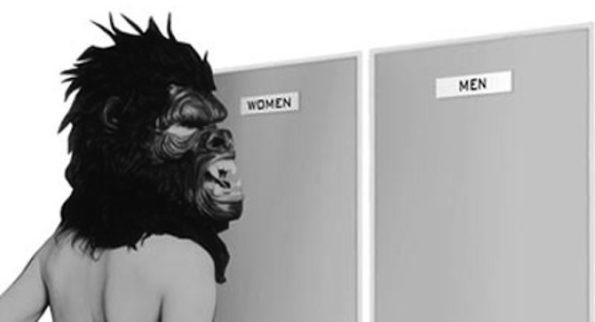

I had this same impression not so long ago visiting the exhibition of the Guerrilla Girls at the Alhóndiga in Bilbao (extended until 19 January) that Leire Vendes Aldabaldetreku talked about here. GoogleMaps indicates that there are 750 metres of the Alhóndiga at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bilbao and 950 at the Guggenheim. Well, the majority of the people who visit, manage, legislate and coordinate these two centres stroll through the exhibition of the Guerrilla Girls with a carefree grin on their face and that expression of “this has nothing to do with me”. The fact that the Museum of Fine Art has not dedicated even one of its 48 individual exhibitions in the last ten years to a woman, or that at the Guggenheim only 9% of the pieces in the collection are by female artists, has nothing to do with the Guerrilla Girls. The gentlemen in charge of such honourable centres will tell you that they are completely different things. If you ask why, their deep reply will probably be that each place is different, that New York is another world and that here what is valued is (sacrosanct) quality. Or something similar.

I’m sorry to say this, but women aren’t subjects of society for all these gentlemen who consider that abortion is our problem, that invisibility is our problem and that being treated as incapable is our problem. We are not social subjects because if male chauvinism affects 51% of society and as a result of these attitudes or lack of positioning by the remaining 49% (my apologies to the exceptions) that it’s still not considered a social problem, it must be because we aren’t part of this society. Eliminate the problematic object eliminate the problem. At this stage any other explanation seems to me incomprehensible. Up to what point will we let them eliminate?

For Haizea Barcenilla art doesn´t seem to exist on its own, but as being interlinked with various social systems, embedded between ideologies and forms of looking, included in exchange networks of, buying and selling, production and exhibition. When she writes criticism, she likes to extend her object of study as much as possible, understanding it through being part of it, considering what her position is. For her, it is impossible to see art without everything else, and everything else without art. And sometimes she manages to interweave the two sides.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)