Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

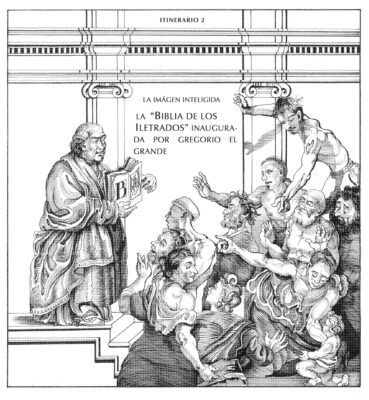

Let’s leave Corinth and move ahead a bit. In this itinerary we will travel to the first centuries after the decomposition of the Roman Empire to see the radical changes of the new religion, secretly created in the catacombs and brought to light by Constantine, delimiting the spiritual substrate upon which rests our continent, often without knowing it. To do this, we will look at three examples that will help us understand the sudden turn that this change represented. The first has to do with the survival of pagan painting in a time of fragility, the “idols,” which must be eliminated so as not to “pervert” our understanding with perishable objects. The second focuses on icons “not made by human hands.” The third exalts Pope Gregory the Great, our protector, and the role his decision played several centuries later in favor of the arts and images, and the patronage the Church gave them when it grafted them onto the very root of its activities during the Renaissance.

Many centuries passed in the Latin-speaking Western World during which the images of ancient art were considered idols, the object of violent controversies. Christianity remained vigilant against the creation of all images, which they considered imperfect imitations of the divine Creation. The preferences of the Church Fathers were similar to Platonism, which, when the Christian era had just begun, had shown itself to be reconcilable with the Bible translated from Hebrew into Greek. Plato’s harsh criticism of the arts and poetry did the rest.

In reality, Plato’s criticism was directed more at the Homeric library and its derivations than at the images of painting or poetry themselves. Plato’s philosophical and political education makes room for the arts, but only the symbolic ones, beloved reflections of ideas and not of things. In this way, an attempt was made to transfigure the artist into a being of knowledge, such that Originals could be contemplated in artwork instead of being considered mere exercises in vanity. Being that the first meaning was so difficult, was it this last meaning, the esoteric, that was accepted? Viewing the course of events, I am tempted to believe this.

In this climate of extreme distrust towards the arts, artisans were given minimal autonomy, without any legitimate right to formal initiative. Such is the case of the icon, including the Mandylion, a fascinating example by an extraordinary Catalan painter that will be commented on later. In the doctrine of the icon, the icon painter is nothing more than an anonymous auxiliary rather than an artist. In his models, the line drawing of the figures is the Idea or Theophany, while the areas of color that serve as a background and the occasional gold or colored glass tesserae that fill in the forms give substance to the Theophany or Idea. This is how the Symbol was expressed, a world unto itself that projected itself into the drawing. In its essence, it is analogous to the relic, the hypostasis of a divine archetype that becomes present by simple contact with the surface.

The role of the artisan was to apply the colors, after which he was to stand back. The function of the true image, the Vera Icon, was the preexistence of its material state, in which a minimum of human intervention was necessary to manifest itself through matter and pigments.

It should be always be remembered that the Latin-speaking West never asked its artists for such a sacrifice, for the simple reason that it did not grant any sacred character to their works. If the work was ever signed, it was to record its ephemeral, simply human and contingent nature.

We had to wait, therefore, for a miracle to happen for the images of art, until then relegated to deceptive illusions for the ignorant, were admitted into the spiritual itinerary of the Christian soul seeking its union with God. This miracle happened at the end of the 6th century, when the bishop of Marseille, Serenus, destroyed all the images, considered dangerous idolatries, of his church’s diocese. The then-Pope issued a bull, reproaching him for having failed in his duties as pastor. By committing such an act, he deprived the illiterate lay person of the only access they had to their faith, making it convenient for them to view “sacred images” which could help them understand the spirit of the sermons.

Gregory the Great defined the Christian visual arts as the “reading and writing of the lay person” which, together with the famous apocryphal letter to the monk Secundinus, established the doctrine of the “Bible of the illiterate.” In the aforementioned letters, in which Gregory was supposed to have accepted a religious man’s desire to pray before an image of the crucified Christ, he admitted that the impression made on one’s heart by external images that represented sacred objects is neither less alive nor less true than those of the fictitious images that are painted in the mind of the observer. In another passage, he goes so far as to maintain that painting excites the soul more than reading, as the former puts facts before the eyes while the latter puts words into one’s ear. The image thus plays the role of a connecting bridge, in which the gift of divine love is understood and received through the eyes.[1]These letters can be found in their Latin version in Gregorius Magnus, Registrum epistolarum, IO, 209 y XI, 10, ed. D. Norberg, 1982, CCSL 140A. And in an English version: … Continue reading

We do not know if the artisans of the time were aware of the responsibility that was suddenly placed upon them, but the fact is that the effect that such a great spiritual authority had by positioning itself in favor of the arts and images was decisive. It is from then on that the workshops and techniques of pagan art were put at the service of the Church, ready to amplify the formula of Genesis, in which the human being was created “in the image” of the Creator, and in which, by the way, introduced the idea of images into the very bosom of God. God is known by his Image, and this Image, incarnated in Christ, visited this world. The door was thus opened for a pictorial art that discovered in the double nature of the incarnate Word a whole series of optical experiments and formal tricks that were conducive to double readings.

[Featured Image: Marcel Rubio Juliana, Dibuix anunciador 2]

| ↑1 | These letters can be found in their Latin version in Gregorius Magnus, Registrum epistolarum, IO, 209 y XI, 10, ed. D. Norberg, 1982, CCSL 140A. And in an English version: https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/01p/0590-0604,_SS_Gregorius_I_Magnus_Registri_Epistolarum_[Schaff],_EN.pdf |

|---|

Marcel Rubio Juliana (Badalona, April 27, 1991). He expresses himself mainly through painting. He is the author of the exhibitions Vastu Purusha (Racoon Projects, 2023), La resurrecció (Fundació Miró, 2022), Hieros Logos (2021) openstudio curated by Margot Cuevas, El retorn a Ripollet (Joan Prats, Art Nou 2020 award), Surfeit ( Arranz-Bravo Foundation, l’Hospitalet del Llobregat, 2018). In the literary field he created with Víctor Balcells Els músculs de Zaratustra (Passatge Studio, 2016), as well as his recent foray into the world of publishing.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)