Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

‘Above all, dear housewife, avoid those beloved little “chats,” on the cellar stairs, in the front hall, before the apartment door, or out of the window, since they are true time robbers!.[1]

‘The first detail which, in the work-day, makes their servitude apparent, is the time-clock. … In a man’s work-day it is the first onslaught of a regimen whose brutality dominates a life spent among machines: the rule that chance has no place, no “freedom of the city,” in a factory.[2]

This text surveys the foundations of the design of one of the most significant rooms in a house: the kitchen. What is its origin? What issues does this space address? The kitchen is one of the most vital places for the material and affective sustenance of life. Given the significance of the tasks required to make life possible – reproduction – in creating the workforce, i.e., given the importance of our bodies being well-fed and clothed, our daughters raised and our grandmothers cared for in order to serve the mechanisms of capitalist production, the design of housework and of the spaces where these are carried out was subject to control by the system.

The contemporary kitchen is inextricably linked to the rationalist theories that shaped the capitalist mode of production at the turn of the century. Its main doctrine was formulated by Frederick Winslow Taylor in the early twentieth century. Taylorism, designed for factory work, enabled the control of labour to shift from the worker (who was familiar with the procedures and managed times) to the planning department, that from then on would organise operations and use a chronometer to increase productivity. This gave rise to a radical change in the economic relations between classes and the appearance of mass production that would be consolidated by Fordism.

In this context, domestic chores began to be systematised, in keeping with the theories designed for factories inspired by activists, housewives associations, industry or the state. The systematisation had a scientific justification, for it made the ways of carrying out housework more efficient, although it omitted the possibility of exchanging it for capital, reinforced the allocation of these tasks to women (the issue of gender was still far from being a topic for debate), regulated them and linked them to products characteristic of the forthcoming consumer society. Through the mythification of the figure of housewife and mother, ‘By denying housework a wage and transforming it into an act of love, capital … has gotten a hell of a lot of work almost for free,’[3] as observed by Silvia Federici. Yet this understanding of domestic work was only one of many that were put forward in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. If these ideas prevailed over all others this was because they adapted to the ideological and economic system of patriarchal capitalism.

In 1982 Dolores Hayden published the acclaimed bookThe Grand Domestic Revolution,[4]

study of the first women who identified the economic exploitation of housework in the United States as one of the reasons for their inequality. These women suggested transforming the spaces dedicated to domestic chores to obtain control over them. Hayden describes different attempts to collectivise housework, such as those proposed by utopian socialists Robert Owen or Charles Fourier, or by initiatives such as those promoted by Melusina May Peirce. Peirce set up the Cambridge Cooperative Housekeeping Society that aspired to organise housework in cooperatives where middle-class and working-class women worked together, all of them shareholders, paid for the food they prepared or for the laundry. Their insistence on being remunerated was provocative, and their husbands felt threatened by their wives’ independence. By 1871, Peirce’s venture, launched in 1868, had failed.

As opposed to stories such as Peirce’s, the proposals for the systematisation of housework made by the so-called ‘domestic engineers’ [5] were more successful. Catherine Beecher was the first of these women. In one of the fundamental books on architecture, historian Sigfried Gideon considered Beecher an important promoter of the mechanisation of the home.[6] Diana Strazdes,[7]

in her turn, thought that Beecher’s idea was reflected in the seventeenth-century puritanical houses of New England, from which she recovered the organisational structure to propose a Christian reform of domestic life. Born in 1800, Catherine Beecher believed in separating the spheres of men and women, reserving the former to public affairs and the latter to the private realm, mythicising woman as a mother and a professional housekeeper, a moral guide for society. Among her many books and articles, the most successful was A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School, published in 1841. This treaty, addressed at young housewives, tackled many issues relative to the home, from advice on diet or physical education to the importance of good manners for domestic and family bliss. Chapter 24 is dedicated to house design, in which she suggested efficient houses and rationalised kitchens filled with light and fresh air. Her vision was completed with the publication of The American Woman’s Home, written together with her sister Harriet in 1869. In this book, the kitchen was a mechanised environment, located at the heart of the home.

Another important influence on the modern kitchen was Lillian Evelyn Moller Gilbreth, born in 1878. Along with her husband Frank Bunker Gilbreth, she was a forerunner in the scientific administration of work and an expert in efficiency, and designed a methodology known as the Gilbreth System with the slogan ‘The One Best Way to Do Work’. Lillian applied her method in her own home, in spite of her dislike of housework and of the fact that she herself, an executive, had household help. In the twenties she collaborated with the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company to develop Gilbreth’s Kitchen Practical, which she made known in 1929. This kitchen displayed the new gas electrical appliances, and presented Gilbreth’s research on time and motion. It was efficiently organised, with counters adjacent to the stove, cupboards overhead for food storage and beneath for storing pots and pans, and the refrigerator close by, all arranged in an L shape. Gilbreth measured the efficiency of her kitchen in steps.[8]

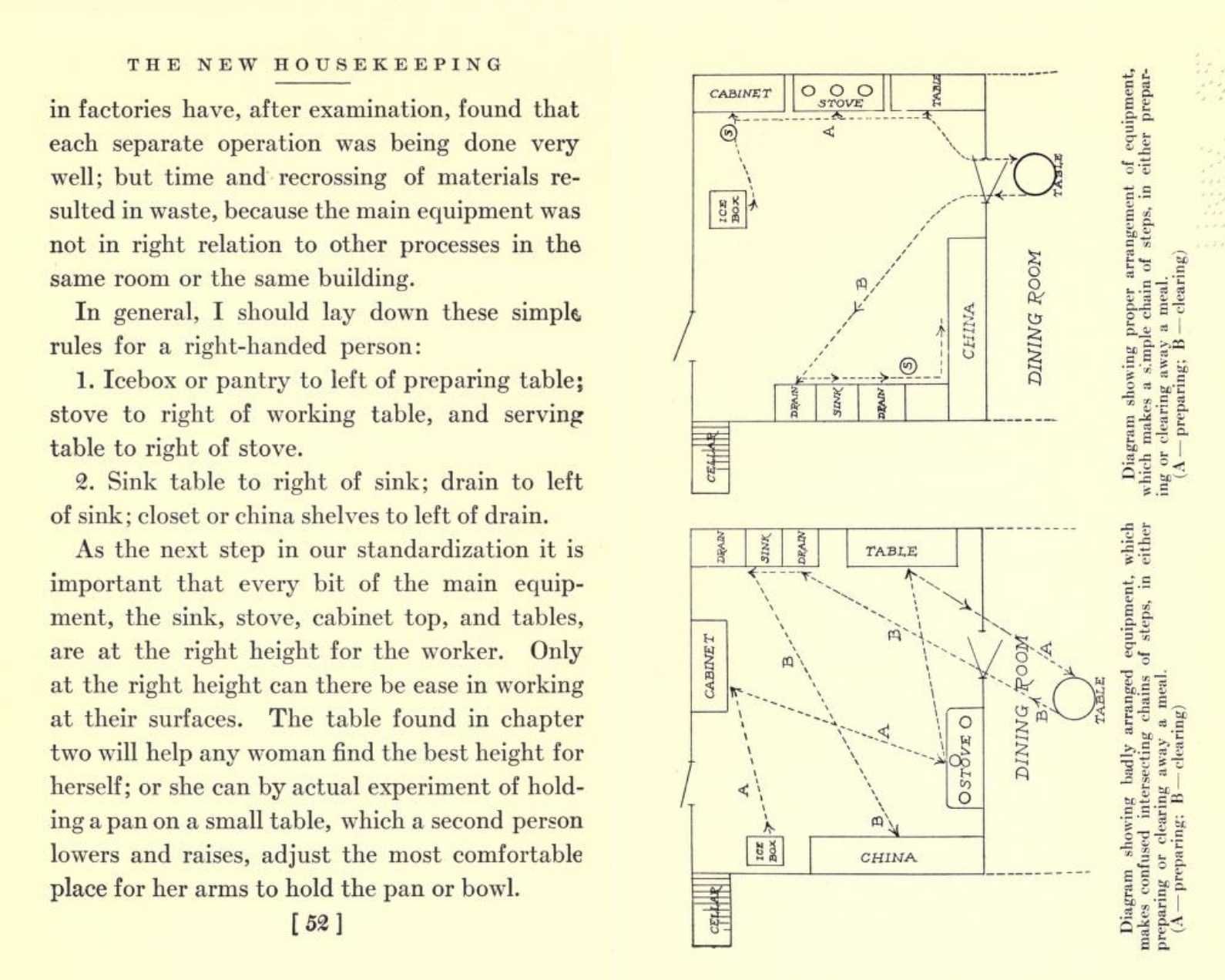

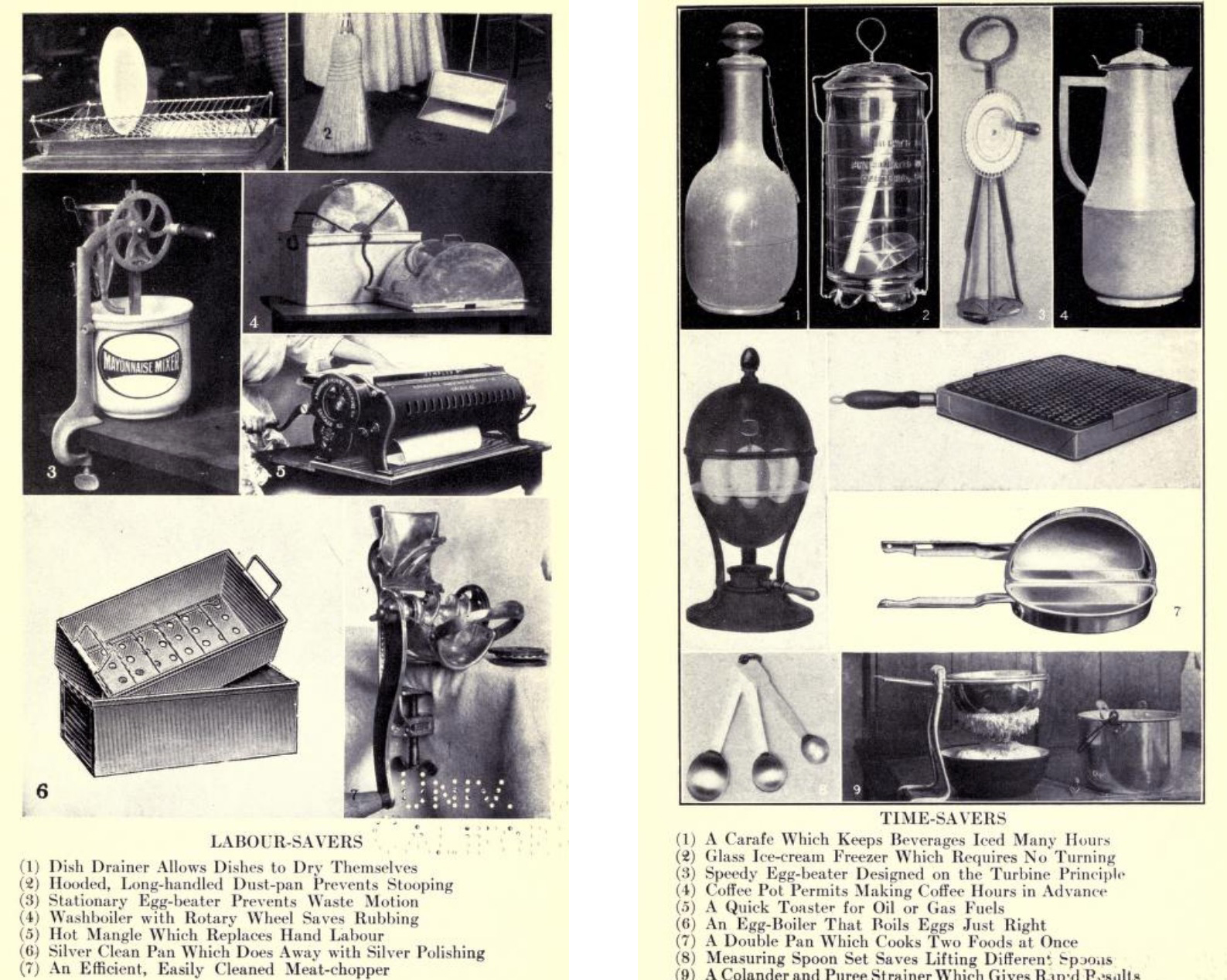

A contemporary of hers was Christine Frederick, the most influential specialist in home economics in Europe. Frederick was interested in the application of Taylorism in the home. In 1912, one year after the publication of Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management, Frederick wrote a series of articles under the title ‘New Housekeeping’ in the Ladies’ Home Journal, in which she aspired to explain Taylorism to middle-class women. The articles were subsequently published in The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management. In the twenties, she highlighted the importance of the planned obsolescence of products as a means of guaranteeing efficiency on a massive scale in order to ensure the industrial economy continues to run smoothly.

In Europe, the rationalisation of housework took centre stage after World War One, a time when nations were following the industrialisation of the United States. The case of Germany has been particularly well studied by architectural historians, who have concluded that domestic space formed a part of the nation’s economic system. As regards housing, in 1921 the National Economy Group within the National Advisory Board for Productivity (RKW for its initials in German) was responsible for disseminating Taylor’s ideas. It set up an educational system, carried out studies on time and efficiency, and created an archive on home economics. A well managed and blissful home seemed to be the perfect setting for efficient workers. Rationalisation appeared as a mechanism of ideological control over the working classes, to which these recommendations were addressed. The American influence arrived through the German translation of Christine Frederick’s book in 1921. The article entitled ‘The Rationalization of Consumption in the Household’ written by architect Erna Meyer in 1922 for a magazine published by the Association of German Engineers (VDI for its German initials) expressed the author’s insistence on the need to understand the home as a productive place that had to be renovated.

According to academic Susan R. Henderson, the work of women like Meyer made home renovation seem a feminist issue, and the involvement of housewives’ associations in its theorising, a participative process.[9] For Henderson, when the kitchen became a consumer product and a disciplinary device, according to which the universal vision of modern life erased social and gender differences, the private patriarchy represented by the family was gradually surrendered to a public patriarchy dominated by industry and the state.

In 1925, Ernst May hired the first woman who graduated from the Frankfurt School of Architecture to design the kitchen that would be built in the 10,000 social houses offered by the local council, governed by Social Democrats. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky designed the Frankfurt Kitchen, modern kitchen par excellence, a space measuring 1.90 by 3.44 metres in which movements could be most efficient. Metal, linoleum, glass and ceramics made it an aseptic space — a laboratory. In 1927 it was shown at the Werkbund Exposition in Stuttgart, where it received international acclaim. In Spain, when modern architects García Mercadal, Arniches and Domínguez published two articles on the Stuttgart exposition in Arquitectura journal, the kitchen went from being an obscure room to a room of vital importance.[10]

The second meeting of the International Conference of Modern Architecture (CIAM for its initials in French), one of the most influential architectural organisations of the time, was held in Frankfurt in 1929 under the title The Minimum Dwelling (Die Wohnung fur das Existenzminimum) and was organised by Ernst May.

Lihoztky’s political commitment was undeniable: a member of the Austrian Communist Party, in 1940 she was arrested by the Gestapo in Austria and received the death penalty, although her sentence was subsequently changed to fifteen years imprisonment. However, the application of technology to solve the problems of the working class, and of working-class women in particular, had numerous setbacks. In spite of the advantages of planning, the crucial organisations and traditions of pre-capitalist economies were omitted. A certain model of family was reproduced in housing design. Technical improvements tempered the idea of class and gender exploitation under the heroic framework of modern constructions. Technology was applied in keeping with industrial interests and the basis of the inequality of women and of the working class was not called into question. The ideas of wages for housework or its industrialisation were never discussed, nor were gender roles or even the very idea of gender challenged. Bearing in mind the importance of salaries in capitalist societies, the invisibility and belittling of care helped keep women away from political, economic and social power.

Dwellings and kitchen spaces were designed according to the productivist values which women were supposed to serve. Yet, as pointed out by Silvia Federici, ‘Only from a capitalist viewpoint being productive is a moral virtue, if not a moral imperative. From the viewpoint of the working class, being productive simply means being exploited.[11] Today, thanks to globalisation, most reproductive work has fallen to migrant women, often employed under irregular conditions. As pointed out by Federici, the question is still that ‘What is needed is the reopening of a collective struggle over reproduction, reclaiming control over the material conditions of our reproduction and creating new forms of cooperation around this work outside of the logic of capital and the market.‘[12]

[1] ‘More Free Time for the Woman,’ Metallarbeiter-Zeitung, 1 January 1927. Quoted by Mary Nolan, in Visions of Modernity: American Business and the Modernization of Germany, chap. ‘Housework Made Easy,’ Oxford University Press, New York, p. 224.

[2] Simone Weil, ‘Factory Work,’ Politics, vol. 3, no. 11 (whole no. 34), New York, December 1946, p. 370.

[3] Silvia Federici, Wages against Housework, Falling Wall Press, Bristol, 1975. Reprinted in Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle, PM Press, Oakland, California, 2012, p. 17.

[4] Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1982.

[5] Carmen Espegel Alonso and Gustavo Rojas Pérez, ‘La estela de las ingenieras domésticas americanas en la vivienda social europea,’ Revista Proyecto Progreso Arquitectura, no. 18 (Mayo 2018), pp. 54-73.

Available at https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/ppa/article/view/3966/4504

[6] Siegfried Gideon, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History, Oxford University Press, New York, 1948, pp. 512-519.

[7] Diana Strazdes, ‘Catharine Beecher and the American Woman’s Puritan Home’, The New England Quarterly, vol. 82, no. 3 (September 2009), pp. 452-489. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/25652030?read-now=1&seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents

[8] Alexandra Lange, ‘The Woman Who Invented the Kitchen,’ Slate, 25 October 2012. Available at https://slate.com/human-interest/2012/10/lillian-gilbreths-kitchen-practical-how-it-reinvented-the-modern-kitchen.html

[9] Susan Henderson, ‘Revolution in the Woman’s Sphere: Grete Lihotzky and the Frankfurt Kitchen,’ in Debra Coleman, Elizabeth Danze and Carol Henderson (eds.), Architecture and Feminism, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1996, pp. 221-247.

[10] María Carreiro-Otero and Cándido López-González, ‘La cocina moderna en la vivienda colectiva española a través de los concursos de arquitectura del período 1929-1956,’ ACE: Arquitectura, Ciudad y Entorno 39, 2019, p. 189. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.5821/ace.13.39.5979

[11] Silvia Federici, Counterplanning from the Kitchen, Falling Wall Press, Bristol, 1975. Reprinted

[12] Silvia Federici, ‘The Reproduction of Labor Power in the Global Economy and the Unfinished Feminist Revolution,’ paper presented at the UC Santa Cruz Seminar ‘The Crisis of Social Reproduction and Feminist Struggle,’ 27 January, 2009. Reprinted in Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle, op. cit., p. 111.

Paula García-Masedo is an artist. She also has published book with Caniche Editorial.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)