Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

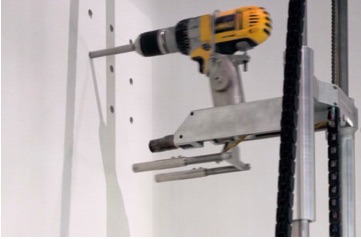

The neighbors of the building started to make holes in the floor and in the walls. The first was the one in the attic, since the man living there said he felt lonely with no one above him. He took the drill and made a hole in the living room’s parquet. The people downstairs were scared at first when they noticed the debris falling from above. They were roommates and at that moment they were about to have dinner. With their screams the drill stopped and a voice explained to them that a real communication channel was needed. It sounded strange, but they understood, and in turn they also took the drill and made a hole in their own wall towards the apartment of an older couple they barely knew. Perhaps it was the deafness, but it took them days to realize it. From then on, the conversations began, shouting or whispering between two people approaching the hole, and a week later the whole building was holed. Some made bigger holes and leaned out of other people’s houses, as if they were leaning out of a patio. Sometimes they passed food with ropes between them or lent each other objects. There were times when the sound of televisions overlapped in a deafening cacophony, so they stopped turning them on. Within a month, the practice had spread throughout the city, and two weeks later other metropolises were joining.

There were neighborhoods that made coordinated holes, making a single hole that went through the building. They went there when they wanted to meet. Others preferred small holes. The strange thing is that, in the end, everyone brought themselves to do it. Other forms of language emerged, specific to each apartment block. There were internal jokes, words related to daily life, to the structure of the building and the views from the windows. The small houses seemed to expand as they merged into one another. When someone got sick, everyone cared of him or her. When someone died, grief was shared. Whoever did not have work to do, helped whoever did. Whoever was paid, shared part of his or her salary. After a while, these practices were condensed into a common box. All rents were paid from there.

The buildings began to have proper names: there were “Crooked stairs”, “Flowerpots”, “Fetid street”, “Old people’s block” or “The Common House”. They also began to compose anthems, most of which superimposed new lyrics to already known music. Those who could, organized themselves to cultivate the rooftops.

At first, the press commented on the phenomenon with sympathy. In fact, many of the journalists lived in holed buildings. After a while, however, the tone changed and the safety of the system was increasingly questioned. It began to be claimed that the holes posed structural problems that could cause the collapse of the buildings. Official inspectors arrived and closed the holes. The neighbors opened them again, in the same place; it happened up to four times. The government was not happy and the landlords were afraid that they would not pay the rent.

Shortly after the arrival of the inspectors, the end of the quarantine was officially declared. On the first day, each building came out as a block. They had sewn suits of a single color and they were singing their own anthems. They looked like some kind of army, walking at a safe distance. Singing, laughing and chatting in what were already dialects, they went to the largest park in the city and, using megaphones, began a huge meeting. It smelled of wet earth and the crowd got comfortable nicely on the grass.

ANTITHESIS: THE RULER

The Ruler lived in a big house with many people. The number of domestic workers far outnumbered his family, but for days he had only seen consultants, advisers, managers, other rulers and usually through the computer screen. Afterwards, he would exercise and go to sleep. However, his nights were filled with strange dreams: he saw old people with drills making holes in the wall haphazardly. He saw children lying down, listening through holes in the floor. He felt greatly attracted to these images, but they also caused him an uncontrollable anguish. He would wake up every day too soon, sweating and with a racing pulse. He never talked about it to anyone, and that is why he could not believe it when one of the consultants told him what was happening in the cities. The Consultant had heard about it from the press: a small report talked about the practice of drilling floors and walls, interpreting it as a measure to bear the quarantine. The Ruler did not understand anything; he was in cold sweat.

Every night his dreams were becoming more vivid, and when he woke up he was in panic. The Ruler no longer wanted to sleep and he spent less and less time in bed. He was tired and found it difficult to follow the schedule of activities that his secretary was dictating throughout the day. With dread, all he could think about was the images he had seen in the darkness.

The Ruler believed it was his dreams that made the neighbors who drilled the buildings. He thought that by prohibiting it, his nightmares would end and he could go back to his usual worries; but it was not working. The inspectors were a failure, and the dreams and drills got stronger the more he tried to suppress them. He decided to end the quarantine. All the experts recommended otherwise, but the Ruler would not listen. Tense from the coffee, he saw with surprise the first exit, coordinated and mysterious, of those neighbors who obsessed him. Of course, there were many policemen following them. He asked his chauffeur to take him to the park as well.

The city smelled of the countryside thanks to a recent rain. The Ruler, exhausted, thought restlessly about the neighbors. It was then when, painfully, he knew that the only way to end the nightmares was to stop fighting them, night and day. Allowing whatever may happen to happen.

His first idea in relation to the park had been to talk to the people, to express his charisma, the power of his gaze, still sharp despite the fact of being now between dark circles. However, when he got out of the car he was speechless. He then walked among the groups, feeling strangely pacified. People recognized him, that was clear, but they did not seem to care about his presence, as if the Ruler and what he represented no longer seemed relevant to them. The assembly began and he sat down next to one of the groups. Cradled by cheerful and determined voices, he finally fell asleep in a peaceful dream.

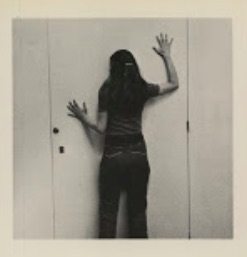

Allan Kaprów, Comfort zones, [(Another private space) A and B, pressing against either side of a closed door / trying to fit the outline of each other / saying, when the fit seems close, only “now” / repeating again and again until certain], 1975

(Highlighted Image: Diller + Scofidio (Elizabeth Diller, Ricardo Scofidio), The MoMA Wall, 2003)

Julia Ramírez-Blanco is an art historian who works at the University of Barcelona where she received a Juan de la Cierva scholarship. Her research focuses on the intersections between art, politics and utopia. She is the author of the book entitled Utopías artísticas de revuelta, in which these issues are examined alongside counterculture and activism. For Ramírez-Blanco, writing is a question of professionalising curiosity and organising enthusiasm.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)