Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

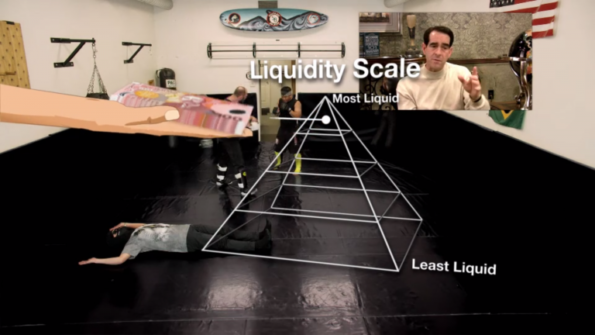

In times of hyper-connection, it is through motion that we calculate the good health of the art world — the more it circulates, the bigger its impact. It travels, it gets de-and installed, sold and bought again, and it is performed and enacted for an international audience dressed in smart-casual attire. As such, it could also be defined by its profitability and efficiency. In this case, counted in amounts of visitors, figures in auctions, or in number of curated biennials. Liquidity seems to be a catchy term that caught up very well in the art world (Hito Steyerl already warned us). Biennials are roaming formats, artists are nomadic, art fairs are transcontinental, blockbuster exhibition are constantly travelling – Art is as fluid as ever. Financialization is pervading social life, trickling down to notions of trust, governance, or legality. As a result, market-value regulates the universal assessment code, and reciprocally, internationalisation has come be an indicator of worth. However, if this kind of transience denotes economic wealth, does endurance unavoidably entail precarity?

Art has a complicated relation to money, often working through elusive concepts such as immaterial value, alternative materialities, or utopias; while art institutions live in loops of (self-) institutional critique and unapologetic complacency. Nonetheless, their symbolic power is undeniable. In the last twenty years, issues of social justice, diversity and equality have moved from the outskirts of their thinking machine to the core. With it, they have taken on the role of agents of progressive social change, and they have come to be respected public forums for encountering and negotiating contested social issues. At the time of writing this article, the Guggenheim and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Tate and London Library in the UK and Louvre in Europe have rejected the prominent donations of the Sackler Family, who manufacture and greatly profit from the painkiller OxyContin, whose usage has unraveled in the current US opioid crisis. These organisations are emblematic paradigms of the above-mentioned flow of wealth-extraction, and yet, they enact their character of protector of social justice, but they do so, in such a fashion that only comes to reinforce the circuit of face value: through money (or, in this case, the rejection thereof). As a result, international press echoes this grand gesture, without wondering why the UK and EU institutions adamantly show (off?) their dismissal when the painkiller is not even sold in their countries; or why they continue receiving money from petrol company, as Tate does from BP; or why the role of the artist Nan Goldin leading the demonstrations under collective P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) is usually forgotten. If the symbolism is only relegated to money, how can we think through art in alternative world-making, new forms of expression, and new utopias? Can an institution with its inherent symbolic power affect value-creation beyond market in the today’s techno-political context?

It is through experimentation and support to the ones who enact it, that the art institutions become valuable for the society they try to call off: offering a space for practice and reflection, fostering collaborations, letting others take over, rehearsing with new forms of organisation to configure new lived spaces. bell hooks asserts, “Speaking is no solely an expression of creative power; it is an act of resistance, a political gesture that challenges politics of domination that would render us nameless and voiceless. As such it is a courageous act — as such, it represents a threat. To talk back is to liberate one’s voice.” I, personally, would like to think that curating can, likewise, be understood as a form of voicing resistance: an ethical endeavour with a social responsibility towards the ones that cannot raise their voices, a way to provide space and empower those who shape the social texture but are relegated to its fringes. Though the making of an institution for everyone is a collective transnational yearning and economically desirable, if I think of commitment to experimentation, radical values, and alternative-world-making, it tends to be born out of generous conversations often served in small doses. To generate social value through those machines in motion seems unattainable, as if we were trading and commodifying its autonomy. Grounded reflection and sincere engagement is a precious mechanism hard to capitalise for the symbolic powers reliant on the global scale of the economic-techno complex, as they tend to happen on small scale formats, working across slow-moving concepts, and in local institutions. They are difficult to make happen, harder to bring up, and even more complicated to work through. Enforcing those tactics might look like a good idea, but when done without a mindful, attentive outlook, in big scale and bombastic production, it feels like artificial sweetening. like the Kabul satellite of Documenta13, which tasted a bit like that Pepsi advertising of Kendall Jenner. Or the ever-growing list of artists boycotting biennales when they are already open. As transnational structures tend to transform radical thought into palatable pills of everyday consumption, collective agency is reduced to money transactions. In this way, converting symbolic power into capital does not entail growing on influence, on the contrary, it is only accumulation in the vacuum of unread international press releases. In this case, internationalisation turns into a currency with inflation.

Perhaps, sometimes, we are looking for grand gestures that could combat all the injustices of the world on a transnational way. But, maybe, the only answer is to respond to micro-geographies of power and control with subtle actions of care, embracing their inherent vulnerability, subverting the discourse of protection and paternalism, to transform them into symbolic power. Maybe, creating an institution for everyone is not the answer, we need to think how to enable new mechanisms to encompass the multiplicity of voices and forms of relations of the congested reality we now inhabit. If internationalisation was the key to neoliberal success, maybe the only way to resist is to become ever more rooted, and from there, to steadily support artists and curators to empower communities through acts of collective imagination. Art practices that catalyse change are not always embedded in global circuits of power, but in mindful rehearsals of freedoms, which grow into micro universes of emancipation and beautiful inefficient artistic productivity. Let’s think of the relevance of these three institutions: Casco, in Utrecht (NL), is working on a long-term programme committed to an exploration of the commons; Aksioma in Ljubljana (SV) concentrates on artistic production based on new technologies exploring social, political, aesthetic and ethical concerns to foster collaborations and exchanges; FLORA ars+natura, in Bogotá (CO) specialises in the relationship between art, nature, and the body. It focuses on an artistic formation that is centred around artistic practice, criticism, and intercultural exchange. Although they are on the edges of the art world, they actively contribute to current discourses that reverberate internationally. Their mission accentuates their social goal through public programming, and the commitment by promoting artistic production and research. In this way, they get to be relevant to their own geographies, as they come to be involved in the production of our individual biographies and collective histories. As such, those experiences are enlightening provocations for the future.

Perhaps symbolic power should also be considered liquid, and as these gestures soak the micro-aggressions with careful empowerment, they permeate bigger textures, becoming impossible to avoid. Through collective voicing, one can subtly impregnate the structures of transnational oppression with fluid, experimental resistances, new collectivity formats, new outlooks for different utopias. Perhaps we just need to appropriate this liquidity, but this time as process, a manoeuvre, as a means to and end, and not as a goal.

(Features images: Hito Steyerl, Liquidity Inc., 2014 (still), HD video file, single channel in architectural environment, 30 minutes. Image courtesy of the Artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York).

Barbara Cueto is a journalist turned into curator turned into researcher and back again. She sees her curatorial practice as research mode, an intersection between artistic practices, science and activism whereby exhibitions become spaces that convey new readings of the convoluted realities we cannot fully grasp and futures that we cannot yet see.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)