Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

At the end of the 19th century, as wax tubes opened the way to a future of new waves, Welsh singer and inventor Margaret Watts Hughes became one of the first women to present an invention at the Royal Society in London.

Mrs. Watts Hughes was also there. She is the lady who sings flower forms on to flat surfaces arranged for the purpose, by emitting notes through a sort of pipe, a performance at which I assisted one-day last season, and which may very possibly lead to considerable developments.

(This quotation, taken from Notes from a diary, 1889–1891, by M. E. Grant Duff.)

Chladni had already made known his work on vibrations, as well as the calculation of the speed of sound for different gases. Ernst Chladni was the pioneer of what was later called acoustics, and Margaret was certainly the first poetic and philosophical attempt to bring this scientific event closer to the world of the transcendent.

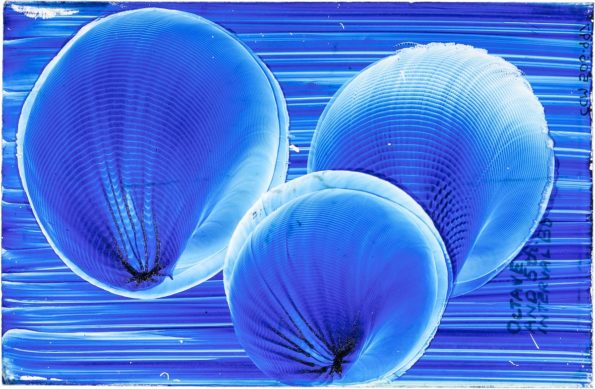

A so-called Impression Figure by Margaret Watts Hughes, pigment on glass, date unknown. Courtesy of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

Hughes’ Ediophone consisted of a kind of funnel covered by a membrane and connected to a pipe through which, by means of the vibrations emitted by her throat, magical shapes were drawn, which she herself called the Shape of the Human Voice.The ink together with other fluids, seeds and small stones vibrated on the surface outlining an unpredictable and organic possibility.

An act charged with equal parts symbolism and simplicity, it served to lay the foundations of visual music. Hughes crafted the most beautiful of cosmogonies, not without science. We are the product of a greater tremor, which shapes and defines us. A sometimes inaudible agitation that constructs us in small, rhythmic sighs. We are vibration.

It is at this point that it tickles in my head, not only a specific name but a way of inhabiting the musical and the creative. A major chord that embraces new sonorities with the naturalness that trees establish, through the phenomenon of empathy, their own space in a grove of trees. I threw two questions at Maria Arnal. I threw two hatching questions at her. But I did it with the certainty that her answer would outline in itself the vibratos of a future.

Es en este punto en el que tintinea en mi cabeza, no sólo un nombre en concreto sino una manera de habitar lo musical y lo creativo. Un acorde mayor que abraza las sonoridades nuevas con la naturalidad que los árboles establecen, por el fenómeno de la empatía, su espacio propio en una arbolada.

Le lancé dos preguntas a Maria Arnal.

Le arrojé dos interrogantes eclosionantes.

Pero lo hice con la seguridad de que su respuesta esbozaría en sí misma los vibratos de un porvenir.

Fito Conesa:The flowers of the voice get their name from their sometimes kaleidoscopic, sometimes centripetal form. If we could see the vibrations beyond the waves drawn by equalizers or audio editing programs (far from the decibel parameters), how do you think they would be, how do they relate to us, colour, density…?

Fito Conesa: When talking about. Vibrations that surround us through the air we are already leaving between seeing concepts such as sound as architecture, that is to say reverberation as a constructive element for example? As an artist / musician who lives in constant LAB, trial and error… How do you embrace reverberation in your work? Would you be able to make an analogy between a musical composition (all its layers and voices / elements that build it) and a garden or a forest?

(Featured Image: Three pitches in an Impression Figure by Margaret Watts Hughes, pigment on glass, date unknown. Note the writing: “Octave and 5th interval Bb”. Courtesy of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum and Art Gallery).

Fito Conesa is an artist and programmer. With a degree in Fine Arts from the UB, he teaches and develops workshops, conceptualizes and produces visual and sound works and curates exhibitions. He was director of the project Habitació 1418 at MACBA and CCCB and was part of the tutorial team of the Sala d’Art Jove in Barcelona. www.fitoconesa.org

Maria Arnal is one of the most admired voices of the recent panorama of Catalonia. Trained in the fields of translation, performing arts, anthropology and singing, she develops her musical work from passionate experimentation with archives and digitized sound libraries of field recordings. She shares her main artistic project with the musician Marcel Bagés.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)