Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

I’m a biologist, an activist in a Chilean sexual dissidence collective, and have worked for over eight years at a medical school associated with a hospital in the public sector and with research laboratories. In this place I devoted myself to studying the cellular and molecular mechanisms through which cancerous cells migrate from their original niche, delicately dispersing me towards other spaces where they proliferate and promote growth. Studying step by step what can kill you in the space of a month or ten years, what situations are altered or which mechanisms lose control from the point of view of cellular and molecular biology in different types of cancer. In this laboratory I must needs discuss the biomedical experiments I carry out with heterosexual men, many of them from Europe or the United States, those who occupy important positions in the field of science in Chile. In the form of a situated narrative, I would like to share some of my experiences through excerpts I’ve compiled in this text. Writing, as feminists have said, has enabled me to survive in these spaces where visibility and power are in the hands of white heterosexual males. These words of mine are a way of creating my sexual exile in a predominantly androcentric context.

***

HospitalEs UNDERGROUND staTiOn

A man is asleep on a dirty, smelly mattress. When he wakes up he reads classical literature out in the open; he makes no movement at all throughout the day. He dozes, reads and dozes off again. Occasionally, someone else brings him a crate of wine and both men drink together on the mattress. I don’t know how he manages in the cold seasons. Opposite the man on the mattress, a woman is blessing those who leave the hospital without having been attended to. Faced with their ailments, all that was left for them to do was let this evangelical woman place her hands on their organs and pray for them in a strange tongue. She asks Jehova to cure those of his sons who are plagued by misfortune. In my opinion, her god is unfair, ruthless even. At street level, at the entrance to the underground station that links to the college, delicious Colombian and Peruvian bread rolls and sweets, along with arepas, sushi and chocolates are sold. The pavement is swarming with women selling medicinal plants, although they the construction of a mega-building that menaces to remove all peddlers is leaving them with less and less space. Small stalls sell clothes for premature babies, combs, underwear, English eau-de-Cologne and pyjamas in all colours and sizes for those who were forced to remain admitted. The families leave the hospital with sad faces, pushing their loved ones along the narrow street in improvised wheelchairs. The authorities, teachers and a few students from the medical school close to the hospital speed past in their cars in search of a place to park inside the college facilities, and therefore have little experience of street life. They were unable to change the name of the underground station, Hospitales, to that of the first female doctor in Chile, Eloísa Díaz, who studied at the same college and who in these feminist days is rightly considered an idol. On the other hand, they decided to build a tiny square that showed the face of the woman forced to study behind a screen in the classroom. I shall never forget that the day Costanera Center, the largest shopping centre in South America, was officially opened someone froze to death outside the hospital. Perhaps it was someone like the mattress man, on the same street called Profesor Zañartu, located at the northern exit of the Medical School campus of the University of Chile.

***

RESIDUAL IMAGES

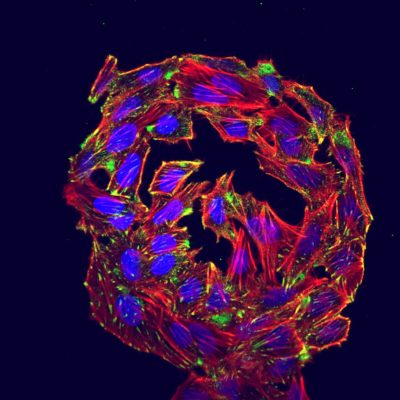

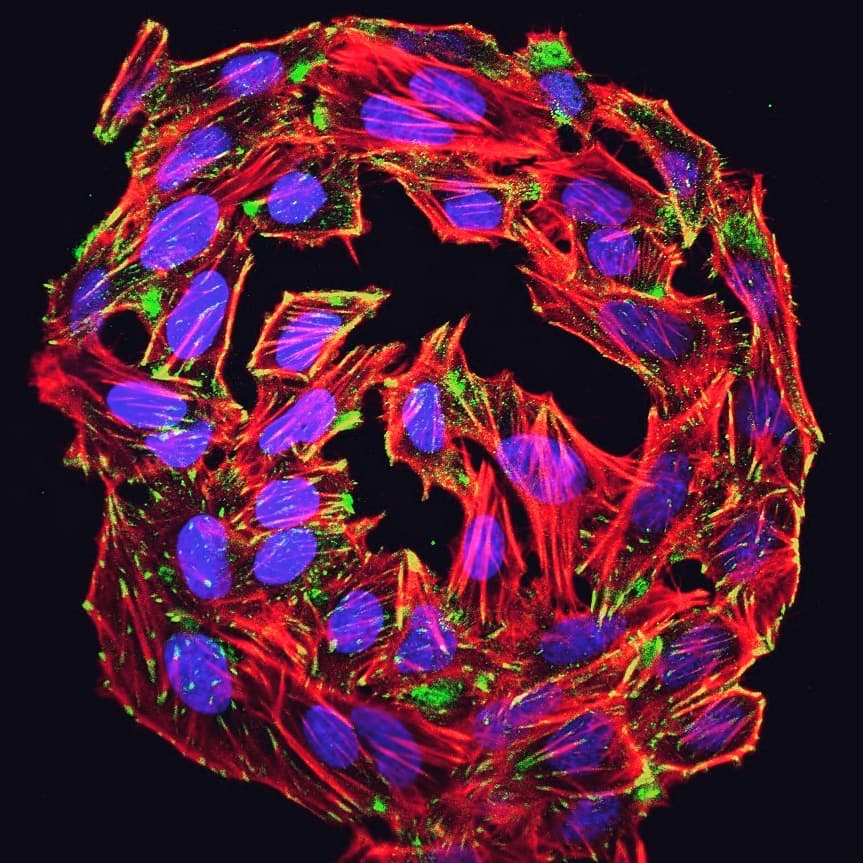

Whenever I look at these cells on the mornings I use the microscope, I wonder what these images can tell me about the social world, about those who disobey, about those who have no place. I know I’m slightly mad because what I should be thinking is whether proteins are activated where they should be activated, that inflammatory stimuli should promote a greater amount of focal adhesions that are the structures through which cells are linked together and with the extracellular matrices surrounding them. I can’t stop wondering what else they could tell me, what other information is contained in these biological aesthetics besides a co-localisation of two proteins and a sign of a greater migratory capacity. I believe these networks of cells with specific tinctions are something more than that. I also believe that we must learn to read this microscopic, molecular universe differently, so that it is isn’t just a number or a graph in an article published in English that will only be read by a couple of scientists in Europe or the United States. That many of these images are discarded because they don’t correspond to the hypotheses posed by our research, that some cells overgrew or adopted an anarchic pattern and were concealed from the dominant regime of visuality, as if they had never existed.

Scientific writing is based on success, on the experiments that turned out well. When I look at these images, I also think of the discarded bodies removed from visibility on account of not corresponding to the ‘normality’ of the hypothesis of compulsory heterosexuality. I think we’ve managed to live on failure, that we must document faults and that feminist science should make room for all these residual images to create another way of producing knowledge.

Figure 1: This is one of several images from various biological tests captured with the C2/C2si PLUS confocal microscope at the Medical School at the University of Chile. This instrument uses high-precision mirrors that allow a high contrast confocal image in high quality. This image cannot be used in the publication of a scientific article; it’s a residual image that was excluded because the cells have overgrown and what is needed to demonstrate a phenomenon are spaced cells, fewer in number. The cytoskeleton is shown in red, the focal adhesions in green and the nucleus of the cells in blue.

***

THE COLONISATION OF BACTERIA

Bacteria cause infections but they hardly ever cause cancer because this illness is produced by other factors, such as genetic charge or environmental effects. Cancer as we knew it so far wasn’t a contagious disease. But this idea has gradually changed. We now know that a certain bacterium, helicobacter pylori, found in the stomach of many people, if infected, could cause cancer. This bacterium can be acquired by ingestion, but can also be activated in the stomach, because sometimes bacteria lay dormant for long periods until something wakes them and they begin to grow non-stop. They’re like the political memory of a country: they can be latent and startling. Gastric cancer is a disease that is spreading very quickly in Chile and for this reason it is the subject of increasing studies. Several people in my laboratory are investigating the effects of this bacterium on cultures of gastric cells, to which they devote much time and enthusiasm. One of the most affected peoples are Indians, particularly the Mapuche, a population in which the bacterium is so aggressive that it rapidly and painfully destroys the lives of many people. The other day at a seminar on biomedicine I asked why this was the case and was told that the reason was that the Mapuche people who had also suffered from this bacteria in another variant had managed to ‘co-evolve’ with it, living peacefully after having incorporated it, whereas a bacterium of Caucasian origin (as they called it) was much more aggressive in the stomachs of the Mapuche because it had reached a previously unknown place and was thus able to cause much more profound and harmful effects. ‘The colonisation continues!’ I told the researcher, who laughed although I don’t think he understood me because the word ‘colonisation’ isn’t often used in scientific writing. The effects of colonisation in science aren’t considered because most of the scientists who occupy privileged positions in Chile are foreigners though not migrants, i.e., they come from the First World. Caucasian bacteria continue silently and painfully killing all indigenous communities. Chilean customs guards are also killing Mapuche people with bullets fired with impunity. Camilo Catrillanca, a young Mapuche ruler who travelled through the southern land of the country, was killed when a colonising bullet went through his head. He had been shot by a Chilean policeman, a cop. They had accused Camilo of being a thief although the law proved that the accusation was false, just another farce of those racist governments that rule us. Caucasian bacteria and the Chilean police continue to kill Mapuche communities. Colonisation never ends. Colonisation isn’t over.

***

THE LABORATORY COAT

I’m a molecular biologist who refuses to use the laboratory coat as I hate its look, its hospital white, its ascetic presence, its standardising purpose, its preventive capacity, its scientific status and compulsory use. Sexual difference in a pleat, a tuck, a given number of buttons. I find such a seriality stifling, for it implies a hygiene that I reject and an average size that doesn’t fit our bodies. Clothes are semiotic technologies that are designed to shape relations, forms of speech and thought. The white coat isn’t naïve; it’s a garment charged with ideology. I remember when as a child I would wear a waistcoat over a beige cotton T-shirt and feel as if I were wearing a dress. I’m writing in memory of all those weird little boys like me whose first hints of transvestism date back to their early school days, minimally altering the dynamics of sexual and class difference found in school uniforms. I’m writing for all those working-class kids who wore our navy blue waistcoats over our beige cotton T-shirts, flaunting our first dresses in society as this was the only way that the other dresses we wore secretly at home could come out into the open. Small transvestite subversions of the effeminate little boy I was. At least I could avoid the obligation of having to wear them or reinventing their use. I need to think of a laboratory coat that fits me, because its use is becoming increasingly compulsory for the rules of science.

***

LIVING A FEMINIST SCIENTIST LIFE

Sara Ahmed speaks of living a feminist life and I think of what it means to live a scientific life as a feminist. It means worrying about the black clams in gel, putting up with a female colleague who shouts when someone left the micro-centrifuge open for a second, not speaking in metaphors, tolerating the competition and silence of people who could help you but choose not to, pushing the limit until the rope seems to snap with your comments, questions and writings on today’s feminist and androcentric thinking. Beware of what you say. Whenever everything is very organised, it borders on conservatism. Adding bibliographies to documents using new software that takes just a second to find references and yet finding no Latin American names, finishing some figures, adding an inflammatory molecule to cells in the nervous system and waiting forty-eight hours until the moment you break the tissues and its molecules are able to swim and float in the alkaline medium in which the experiment will take place. Knowing that you’re surrounded by homophobes who may perhaps never confess the fact, as it is a word that shouldn’t be pronounced. And carrying on quantifying, quoting statistics, assembling other figures, wedging lines — time goes on. Reading an interview with Donna Haraway, American feminist biologist, and feeling the weight of the privilege of compiling a history of science in a city with beaches where lesbian women marry homosexuals and together make their homes into places for experimenting with metaphors. The heterosexual privilege of local science means the success of heterosexual couples whose laboratories are extensions of their homes. Scientific research is made for curious minds yet indifferent hearts. I love challenges, thinking up experiments, seeking new solutions to molecular problems, improving the control of experiments in order to understand the changes caused by the use of certain drugs. Collaborating, working with others, looking at the microscope, which is like my eyes contemplating galaxies in bright baroque colours and dreaming for a moment that I’m in a cellular transvestite club where molecules are the singers and their locomotion structures are the accessories that any drag queen could possibly need. Assembling molecular structures resembling puzzles that explain the molecular routes I’m studying. Seeking the best way of presenting my results and remembering the Russian dolls that always surprised me as the smaller they were, the more fascinating they seemed. Scales and their questioning are important in biology. The beauty of Russian dolls doesn’t lie in their arrangement but in the process of assembling and disassembling them. Feeling privileged for being an enlightened member of the working class in a country where education is a business that doesn’t embrace contingent workers.

I decide to wear two hoop earrings but choose not to make up my eyes to go to the laboratory.

Jorge Díaz. Biologist, writer and sexual dissidence activist (CUDS). D. in Biochemistry from the University of Chile, he is currently developing post-doctoral research in the area of neuroscience at the University of Chile’s School of Medicine. He recently published a trans-disciplinary research with photographer Paz Errázuriz called “Ojos que no ven”. He works on collaborative projects and workshops in art, feminism and writing trying to cross genres and disciplines.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)