Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

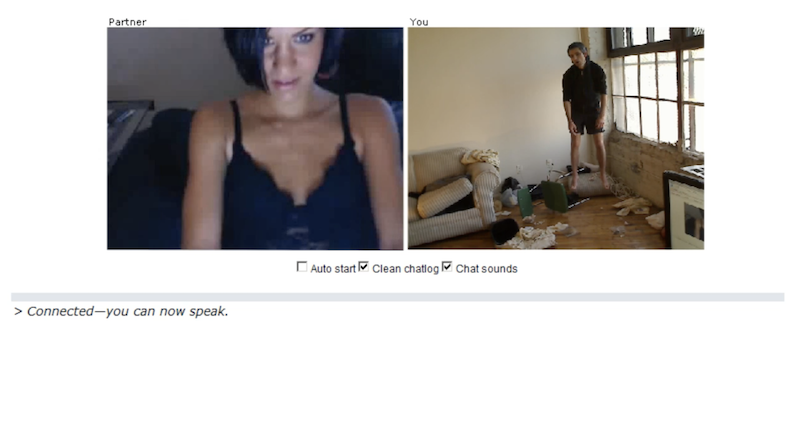

The video shows two screens. On the screen to the left, faces of people looking at the camera in alarm, laughing, checking each other out or remaining speechless. A hanged man appears on the screen to the right. No Fun (2010) is a performance by the artists Eva and Franco Mattes made on Chatroulette[1]Chatroulette was created by Andrej Ternowskij in November 2009 and gained notoriety in 2010 for its users who spread obscene acts. https://chatroulette.com/, a website that randomly matches the webcams of its users. The artists took advantage of this social and entertainment platform to create an unexpected encounter with a tragic event, recording the two images live as arranged by the interface, one next to the other. Without manipulating anything other than the fiction created by an actor hanging from a false noose, they manage to create a split-screen effect similar to that used in film scenes in which narrative tension is created through communication between two characters in different places, usually with one of them unable to reach or save the other from imminent danger[2]It is precisely this situation that is narrated in the silent film Suspense (Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley, 1913), one of the first to use this technique.

Eva and Franco Mattes have worked throughout their careers creating fictions by manipulating media[3]In the late 1990s, they made their name by creating a fake Vatican website and by copying other artists’ sites. Later, they created more elaborate fictions, such as Nikeground (2003) and United We … Continue reading but this time they use a clearly cinematographic language to explore similar resources[4]In Emily’s Video (2012), the artists carry out a collaborative performance in which diverse people record themselves reacting to a supposedly lurid video (perhaps a snuff movie), which viewers … Continue reading. In this work, the Chatroulette interface itself works as a readymade of the classic split screen used often in films and television series to show two people talking on the phone. What originally was meant to remind the viewer that they were watching an elaborate and edited fiction, breaking with the pretense of the reality of the image occupying the entire screen, becomes a truthful record of a form of daily communication. It is precisely the everyday nature of videoconferencing that makes it possible to create the effect that the artists seek, with randomly chosen users (mainly teenagers) engaging in leisure activity. Mattes’ work leads us to consider three aspects of the use of the split screen by artists who work with digital media today: first, the combination of two or more geographically distant spaces in a single space that it is neither of them, but rather, a heterotopia[5]Michel Foucault (1967) “Des especes autres,” Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, nº5 (October 1984), p. 46-49.; second, playing with cinematographic language to elaborate a narrative with found elements that develops without the control of its creators; and, finally, the use of juxtaposition to create tensions between more or less disparate images, which acquire meaning thanks to the comparisons established between them.

Eva y Franco Mattes, No Fun (2010)

The physical distance that separates Chatroulette users from the fake hung man in No Fun is a key element in their reactions, which range from mockery, disbelief, and despair at not being able to do anything. To add realism to the scene, the artists left a computer on that displays the image of the user in the lower right corner, thus introducing the viewer to the image they are viewing. This gesture adds a mise en abîme that reinforces the conception of the computer screen as a space of an infinite number of places. This idea is perfectly illustrated in the work of Joe Hamilton, whose videos combine natural and architectural spaces in dynamic visual compositions that question the separation between the natural and the artificial, reality and fiction. In Hyper Geography (2011), the initial sequence begins with the screen of a smartphone, which becomes the window through which we observe a world made up of fragments of images that are integrated into glaciers and mountain ranges. Raised in the culture of digital collage, Hamilton has been inspired by the possibilities that platforms such as Tumblr8 offer for the creation and dissemination of content on the web, developing his work based on found images. However, in later videos he incorporates techniques from cinematographic language, notably in Merge Nodes (2016), where he explores split screens, change of frames and the transitions between scenes filmed in different places on the planet.

Joe Hamilton, Hyper Geography (2011)

Heterotopia also takes shape, albeit in a more subtle way, in Nicolas Maigret’s installation The Pirate Cinema (2012-2014). Composed of three screens on which files obtained in real time on P2P networks are projected, the piece translates into a cinematographic collage of short fragments of pirated films that users share privately. It is of particular interest the fact that the artist decides to show this rapid succession of images not on one but rather three screens, thus building a triptych that can also be conceived as a split-screen narration. The physical distance in this case is between the users who share the files, represented by the IP addresses of their computers and the country in which they are located. In this case, communication takes place between machines and not people, the spectators witnessing multiple exchanges that take place simultaneously on a global level. Maigret’s work also lends itself to being interpreted in montage form, since the random juxtaposition of images leads us to construct a narrative, however implausible it may be.

Nicolas Maigret, The Pirate Cinema (2012-2014)

As Gene Youngblood announced in 1970[6]Gene Youngblood (1970). Expanded Cinema. Nueva York: P. Dutton & Co., Inc., p.191., the computer is not a simple tool but rather an active participant in the creative process, opening up new possibilities for audiovisual creation. Maigret’s work introduces the automation of montage and the random selection of content. Grégory Chatonsky has explored over several decades the possibilities of this “expanded cinema” to which Youngblood referred with work that uses well-known feature films as raw material. In 1+1 (2004), the film Nouvelle Vague (Jean-Luc Godard, 1990) is presented on split screen. Different scenes are reproduced randomly on both sides, generating a juxtaposition of spaces, situations and dialogues. In 1-1 (2004), the famous shower scene in the film Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) is subjected to a random montage, while 1=1 (2004) shows on a horizontal split screen fragments of the film Lost Highway (David Lynch, 1997), chosen based on the appearance of a character and his double, offering the viewer the possibility of reproducing different scenes. All these narrative experiments are based on the possibility of generating an infinite montage, by means of the random combination of sequences and the multiplication of images that, especially in the case of Chatonsky’s work, lead to another common use of the split screen, which is the combination of different points of view of the same scene.

Grégory Chatonsky, 1=1 (2004)

These works offer us a sample of the creative possibilities of the split screen in the context of the rapid proliferation of images on a global scale, allowing us to imagine all spaces as potential heterotopias. Our personal space is always capable of connecting with other spaces (remote or fictitious) through the screens of our digital devices, and also of being observed from multiple perspectives. In the same way that the split screen ends what Peter Greenaway calls “the tyranny of the frame[7]Peter Greenaway (2003) Toward a re-invention of cinema. Variety, 1 octubre. https://variety.com/2003/voices/columns/toward-a-re-invention-of-cinema-1117893306/,” the inexhaustible plurality, together with the generative potential provided by computers, means that narratives can never be unique or complete. They will always be a fragment of a longer and more complex story, just one of an infinite number of ways to tell it.

(Cover image: Nicolas Maigret, The Pirate Cinema (2012-2014))

| ↑1 | Chatroulette was created by Andrej Ternowskij in November 2009 and gained notoriety in 2010 for its users who spread obscene acts. https://chatroulette.com/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It is precisely this situation that is narrated in the silent film Suspense (Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley, 1913), one of the first to use this technique |

| ↑3 | In the late 1990s, they made their name by creating a fake Vatican website and by copying other artists’ sites. Later, they created more elaborate fictions, such as Nikeground (2003) and United We Stand (2005). |

| ↑4 | In Emily’s Video (2012), the artists carry out a collaborative performance in which diverse people record themselves reacting to a supposedly lurid video (perhaps a snuff movie), which viewers cannot see and must imagine from the facial expressions of those who participate in the piece |

| ↑5 | Michel Foucault (1967) “Des especes autres,” Architecture/Mouvement/Continuité, nº5 (October 1984), p. 46-49. |

| ↑6 | Gene Youngblood (1970). Expanded Cinema. Nueva York: P. Dutton & Co., Inc., p.191. |

| ↑7 | Peter Greenaway (2003) Toward a re-invention of cinema. Variety, 1 octubre. https://variety.com/2003/voices/columns/toward-a-re-invention-of-cinema-1117893306/ |

Pau Waelder is senior curator at Niio. Writer and researcher specialized in art and digital media. PhD in Information and Knowledge Society from the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC). Adjunct lecturer at the UOC, as well as in postgraduate courses. Editor and advisor at DAM Digital Art Museum. His work explores the different aspects of the interaction between art, technology and society, as well as the relationship between digital art and the art market. He is the author of the book on contemporary and digital art collecting You Can Be A Wealthy/ Cash-Strapped Art Collector In The Digital Age (Printer Fault Press, 2020).

www.pauwaelder.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)