Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

2020, global crisis in a continuum of specific crises. Right now, in the form of viral pandemic. A pause in the system, a part of the machinery has stopped and the other one going at full speed. And in this out of sync context, the moments and situations for the exchange of ideas and for sharing art and culture become something out of place; an uncertain future is presupposed. In the face of confusion, it is even more important to talk about how a system is defined, what the situation is regarding institutional critique and where we currently are or where we can be. Recognising ourselves in the moment, the assumption of a previous process and the desire to rethink forms is what will make visualising as an option actually possible, a potential reality, a myriad of situations to compose a multiplicity of possibilities.

The ecosystem of art has in balance one of its best tools for survival. Agents and structures need to recognise each other from all positions in a symbiotic truss that calls for solidarity. But the reigning economic system defines itself through struggle and competitivity and it has seen how its speed of action increased considerably: global liberalism defined many ways of acting, also regarding art. It is probably now when it’s more important to rethink the institutional framework again, thinking of it from the public responsibility with regards to the ecosystem itself and society itself. And public responsibility isn’t necessarily synonymous with public organisation, but rather with the definition of contexts and arenas where being a critical society, that option that seemed to have stopped existing, is possible. Mark Fisher commented —before the pandemic— that in the face of the neoliberal collapse, new forms of solidarity would be needed, however, solidarity wouldn’t appear automatically and —for that— new types of institution would have to be invented.

And in the proposition of arenas for new forms, the artistic institution plays an important role. The critical rapprochement to institutions has gone through different phases. We saw how some conceptual artists understood the work of art like a field of critique to the institution. Hans Haacke opened up the range through surveys and documents to make the framework behind after institutions visible, as well as their economy and decision-making. Marcel Broodthaers personified institutions after making museum language his own work. Guattari —together with the Cerfi investigation group— received commissions from the French State to rethink the idea of institution in order to find a relationship of trust with the population. On the artistic institution specifically, Brian O’Doherty discerned around the ideology of the white cube so that it would finally stop being assumed as something neutral. Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger would find spaces of artistic work outside and in parallel to the institutional framework. The writing of art history would then go through many hands (and latitudes) that only those in the big museum in New York and the languages and rhythms would escape from the frameworks. A journey in which from artistic practise and thought, the idea of institution was in question, but in which the institutional structure was strong —and opaque— enough for it to survive critique without a problem.

So, the viral mode. Andrea Fraser would speak from the seduction of power that institutions represent to reach a physical (and psychotic) relationship with institutional architecture and its characters. Under the direction of Manuel Borja-Villel, Fundació Tàpies in Barcelona presented the exhibition “The End(s) of the Museum” (with John G. Hanhardt and Thomas Keenan as curators), raising questions about the future and the definition of the institution through artistic approach. Relational art would turn museums into places to (artistically) eat with Rirkrit Tiravanija and Palais de Tokyo in Paris would —temporarily— become a key point to observe in order to check whether the experiment would be able to change the status quo. The institution incorporated critique as part of its program, and it felt more flattered than attacked, and understanding that the people working within it were not the enemy, but rather part of a truss. With different positions, but inside a shared context. As Andrea Fraser said then: “We are the institution”. She also commented —afterwards— the leap from institutional critique to institutional analysis, something that implies a desire to enter it in order to modify it, an almost psychoanalytical approach to work with the “problem”.

On a parallel story, feminism was aware of the onset of plurality to become different options with different levels of openness and struggle, voices were multiplied and constellations covered different layers. The thought based on queer theories would dismantle many principles that were taken for granted to offer then, through Judith Butler, a kind of porosity and performativity that involves the active reformulation of the concept of identity. The multiplication of worlds would imply, in this case as well, the rethinking from the writings of history (beyond the postcolonial critique, at the hands of Elisabeth Freeman), to the physical construction of worlds with Karen Barad. On another parallel story, performativity in politics brought the investigation of participation as a tool of definition, trying to generate new political forms outside the traditional framework of parties and unions.

Everything in a relatively short period of time. That speed also turned to historical gestures and institutional analysis offered a wide vocabulary from which it was possible to raise new starting points. A textual vocabulary like the one Nina Möntmann contributes with when she speaks —for example— about opacity and desire, or a vocabulary through institutional experiences like Maria Lind proposes through her expanded program in Kunstverein in Münich, or the institutional experiments Charles Esche made in the no longer existing Rooseum in Malmö. The art ecosystem moved from the most local outlook to the most international one in small periods of time and phases. Phases that were almost understood as individual experiments used to add up in professional careers. At the same time, political evolution places us in front of involution with the clear privatisation of the public sphere, control through fear, the support for populism, the simplification of language and a process of absolute invisibilisation of ideas.

Then the public sphere. The artistic institution becomes —probably by omission— one of the few places where belonging to the public sphere without following exclusively the liberal economy judgement is possible. Languages are not closed, rules are not clear, the public is not necessarily composed by consumers nor clients, success cannot be quantified and the possibility of stopping time to work in different ways exists. Exhibition halls and other places in the institution aren’t the mall, nor the public square with police control and publicity. Exhibitions are situations where one can propose ideas and ideologies, emotion and thought, language and reformulation. We are talking about an almost secretive institutional context, if it were mainstream or if it had a strong economic structure, if it were massive —therefore, a market— it would hardly behave with such criteria of freedom and constant possibility of error. “Art is for everyone, but only an elite knows it”, as Dora García stated in one of her golden sentences. The door is always open, but knowing where it is or if you need an invitation to go in isn’t easy. The institutional network is like a series of cells of a parallel system, probably situated in a time somehow different to the norm.

Like in every ecosystem, the possibilities of experimentation are found more easily in institutional contexts that have less visibility, so it’s logical that they’re not as evident in big museums but rather in art centres. Contemporary art museums tend to also function as an art centre to link themselves to present times and define and frame their future work with history. That way, (at least in some parts) museums can be places in which they can open up to the generosity that experimenting implies. Generosity that is found in learning processes, generosity that means to lose control, generosity that is not knowing what is going to happen. Solidarity that is to listen and to be institutionally receptive, solidarity that is to recognise the ecosystem and the responsibility it entails.

The many decades of critique and institutional analysis have allowed to name and detect options, but we seem to be now in the face of a likely next step: that change can affect the structure and that institutional critique isn’t made from an existent reality, but rather generates it. Institutional critique was able to add up a vocabulary, a desire, a map for a rethinking. But most institutions still have the same DNA with the same rhythms and formats, they share the idea of what is public, but understanding public function as something unitary and democratic in itself. If identity is variable, if history cannot be written with the same words, if the relationship with the world is different, if politics are also calling for a reformulation, isn’t it time to do so from the artistic institution? Isn’t it time to reformulate structures? The new left-wing politics have doubted contemporary art, probably because art goes for a complex multiplicity of identities. Multiplicity implies the impossibility of a closed and unique discourse, which implies imbalances. Imbalances that define art, with the impossibility of easily answering questions like who we are, what we are and what we do. Imbalances that are conflicting with a liberal system of winners, but also in imbalance with the politics of struggle. At the same time, it also isn’t surprising that one of the places the new global extreme right decides to attack is contemporary art and identity politics: it is here where complexity appears, it is here where simple discourses are dismantled in the face of a complex reality.

In this context, in this crisis, we see in institutional options the proposals to change the idea of institution in itself to be able to rethink their role in the ecosystem. Manuel Segade shared the process of architectonic acupuncture in the CA2M as an example that architecture responds to art and not the other way around, generating that way a continuous dialogue to open possibilities up. Also in the CA2M, the educational program is a living organism that can be used to work with ideas that define the identity of the art centre in the present and in the future. From Bonniers Konsthall, Theodor Ringborg wondered whether it is necessary to follow a museum tradition in the presentation of art in an institutional context or if, au contraire, we should question what we understand as “knowledge”. Stefanie Hessler took a chance on longevity without stagnation and for institutional porosity, assuming that whatever happens outside an institution like Kunsthall Trondheim is also a constitutive part of what’s institutional and viceversa. In Index Foundation, different rhythms and ways of doing things coexist: some exhibitions are born as experimentation from learning, some artists aren’t invited to make exhibitions or to produce, but rather to simply maintain a dialogue. Roles and functions are constantly interchanged. Chus Martínez presented her work in the Art Institute in the FHNW Academy as a tangled truss in which everything is interconnected and emanates from specific ideological values. Those values will define the institution, which is something we can never forget. Again, a new institutionality now in times for solidarity, in times in which emergency is calling for public context in order to rethink actions, identities, creation and artistic work.

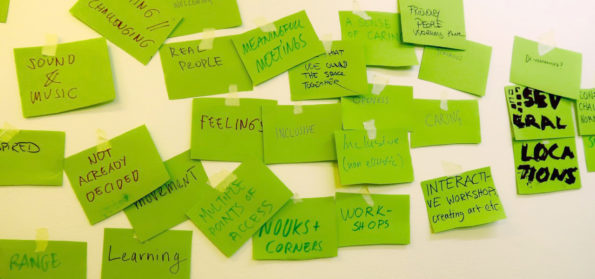

(Featured Image: Index Teen Advisory Board workshop on the ideal institution, 2020)

Director of Index Foundation, Stockholm, exhibition curator and art critic. Yes, after Judith Butler it is possible to be several things at once. He thinks that questions are important and that, sometimes, to ask means to point out.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)