Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

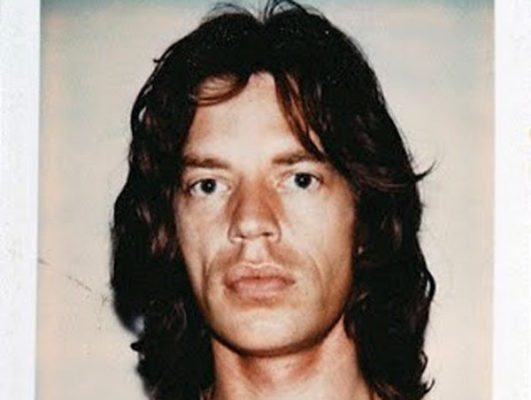

The Polaroids by Warhol, as a system for maintaining emotion and memory, have currently taken on a new life. Their diffusion in various art centres and museums across the world responds to the desire of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the artist to remain one of the definers of an era that is still our own. In Madrid, Warhol now has a multiple presence.

Within the programme of Photoespaña 2012 it has been decided to take yet another look at Warhol. Held not in vain as one of the most important artists of the 20th century, the time still hasn´t come when turning to look once again at his work isn’t pertinent. A double programme, with an exhibition in the Teatro Fernán Gómez and a cycle of projections in the much loved Cine Doré. In the latter (curated by Douglas Crimp) it is possible to see some of the films produced by the artist when resident in New York. In the first (at the hands Catherine Zuromskis) a survey of what the Factory was, that artists’ studio that has left us, above all else, the valuable relic that is the action of manifesting, with pride, the importance of the affective as what sustains the defining universes of art.

The show “From the Factory to the world. Photography and the community of Warhol” honours the amplified personality that this space generated, that transcended the leadership of its founder. As well as his work it presents the work of artists who participated in the Factory phenomenon, such as Billy Nawe, Chirstopher Makos, Brigid Berlin, Cecil Beaton, Jonas Mekas, Richard Avedon and Stephen Shore.

However, in thinking about this multitudinous personality, not exclusively to this specific place, but almost collaterally in all those other spaces defined and managed by artists, a correspondence forms in the mind between this mode of making photographs, precisely that of the Polaroids of Warhol. What have they ended up being, if not an index of the material upon which the Factory was sustained, the human affinities between more or less recognisable signs of a certain universal culture?

Each time I see the Polaroids by Warhol I’m surprised by how recent a past they seem to come from. And it still makes sense to ask today how these portraits taken thirty years ago age. These images are still not thought of in historical terms, not because one doesn´t want to, but because the historical is just not part of their makeup.

Andy Warhol took more than 30.000 Polaroids between 1970 and 1987, the year of his death. Some of the photographs are familiar to all of us, but the majority have yet to be exhibited to the public. We think they are familiar for a variety of reasons. The first, undoubtedly, is the frequency with which we have been exposed to them. Since 2007, in celebration of the 20th anniversary of the artist’s death, the Warhol Foundation decided to make massive donations of the archive to educational and contemporary art institutions; which have since been exhibited and paraded ad nauseam. In accord with the artist’s policy of self-promotion, the foundation that bears the name of Warhol, managed in this way to disseminate his work, leading an infinite number of indexes to the main archives.

The Polaroids by Warhol are also familiar because what they show is familiar to us. The familiarity of their content lies in the fact in that those portrayed, many of them recognisable faces, are made up and disguised and as such, converted into anybody. Simplified and universalised, their particular peculiarity, means they can’t be anything else but ours. Flattened and bleached out in order to be used later in silkscreens, they all participate in the shared essence of the frame in which they are located. How potent and real is the superfluity of these photographs. But, above all, the reality and superfluity of the experience they presuppose: that of going out partying, cross dressing, getting all made up and posing in front of a camera with as little solemnity as a Polaroid. Their levity is the inventory of the volatile phenomena they register.

The Polaroids by Warhol, any of them, lots of them together, the more the better, show as such the need to work together. They are always in a present that begins in the seventies and that continues even today, in its own particular way. And in part, one small proof that this present still continues today is because somehow or other we recognise our own imprint in these images. They are the way they are, we know they are, just as we know they could be different. But they aren’t. It is the image itself and the flash does it justice. It fixes in an instant this outburst of energy that each disguise brings with it. These images function as a register of professional dynamics constructed upon the vectors of friendship.

And maybe, just maybe, Barthes was right in defending the strength the emotive has for creating a bond with images. Naturalness, however critical we might be, sometimes still moves us. Because when we go, like now, to look at the repertoire of things that happened in a midtown New York space, we see something more than images.

It may be, that actually, in a time like today, the very volatility of our emotions is the only thing that can establish links with some of the images that saturate our universe. And maybe the naturalness of how it is inscribed in a work unleashes an emotional bond, even if within the framework of the contemporary it becomes something classical.

Paloma Checa-Gismero is Assistant Professor at San Diego State University and Candidate to Ph.D. in Art History, Criticism and Theory at the University of California San Diego. A historian of universal and Latin American contemporary art, she studies the encounters between local aesthetics and global standards. Recent academic publications include ‘Realism in the Work of Maria Thereza Alves’, Afterall, autumn/winter 2017, and ‘Global Contemporary Art Tourism: Engaging with Cuban Authenticity Through the Bienal de La Habana’, in Tourism Planning & Development, vol. 15, 3, 2017. Since 2014 Paloma is a member of the editorial collective of FIELD journal.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)