Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

On the one hand, we have the MOUTH, one of the bodily holes that acts as a border between our interior and the world, between our body and those of others (whether they be human beings, animals, plants, inorganic elements or objects, or beings belonging to any other intermediate category). A hole that is at once the beginning and an essential part of the digestive apparatus; a masticating cavity where the first phase of the process of ingestion takes place, and therefore the first phase in which our body assimilates one or multiple exogenous bodies. On the other hand, we have the STONE, an element that in its wide variety of shapes, sizes and typologies provides us with unique astrobiological information on the earth and its evolution. We soon learn that stones and mouths shouldn’t be connected, that we don’t eat minerals.

Since 2014, artist alfonso borragán (Santander, 1983) has been working on an art project entitled Litófagos (Lithophagous) that challenges this assumption. This transdisciplinary investigation explores the cultural practice of stone eating, also known as lithophagy, from the fields of anthropology, mythology, history, science and art. In my conversation with borragán – from which this article stems – the artist tells me that over the course of time, and even nowadays, the ingestion of clay, silt and other mineral forms has been a constant presence in many cultures. As early as the days of the pharaohs, the inhabitants of the Nile Valley regularly ate sheets of silt deposited in the riverbed or on the riverbanks, while in classical Greece the pharmacological compound terra sigilata prepared with white clay from the island of Lemnos was used to treat a number of complaints, as well as being an antidote to poison. Apparently discovered on the Greek island by Galen, the Greek physician took it to Rome where the widespread fear of being poisoned to death made it hugely successful. The artist also tells me that different types of stones are regularly ingested in several African communities, and Haitians prepare traditional galettes de boue. borragán believes that these customs are related to beliefs rooted in ancestral ritual practices. ‘There is the belief’ – says borragán – ‘that clay is a regenerative element, capable of making grow what you are lacking, be it a finger, a thought or an energy. And that stones give us the memory of bygone days that cannot be reached by human biology.’ Geophagy, which is the name given to the practice of ingesting earth or earthy substances like clay, silt or chalk, was in fact a frequent nutritional behaviour in rural and pre-industrial societies. With the onset of modernity, and with colonialism lurking darkly in the background, all these practices became stigmatised. Yet it may not be necessary to look to other cultures to discover the presence of practices connected to the ingestion of minerals: almost all small children are attracted to eating earth and sand. Those who continue to feel the need to eat earth and similar elements after their childhood days are diagnosed with Pica Syndrome, also known as allotriophagy, a disorder characterised by the irrepressible desire to eat or lick certain inedible substances, including earth, bicarbonate, paper or wood. Over and above the psychological causes that make this a pathology, such behaviour could also be motivated by our nutritional needs, as some minerals, like phosphorus, calcium, zinc or iron are present in our organisms and are essential for its proper functioning.

Archivo Litofagos: low cost endoscope. USA army, 1961.

As an artistic research project, Litófagos is theoretically nourished by information, images and documents related to all these practices and to their evolution over time; it even includes references to other creators who have explored similar themes starting from artistic practices, such as Lindsay Seers or Jennifer Teets. Yet far from remaining in the theoretical framework, Litófagos is articulated, above all, by a series of community stone-eating practices, artistic-cum-ritual lithophagous acts in which stones are processed and served to those participants who feel like ingesting them.

The first of these actions took place at the Banff Centre, located in the national park of the same name in the Rocky Mountains of Canada. The stones in that park are national heritage and cannot be gathered (and even less eaten). Yet borragán and the other artists with whom he performed the action – the Postcommodity collective and Dustin Wilson – found a way of obtaining and eating stones that were like those in the park but were private property. They discovered that the floors of the basement rooms in the Banff Centre, built atop the mountain, were made of the soil of the mountain itself that had infiltrated the building. The collective ingestion of a stone from this mountain was one of the five actions that borragán and his colleagues carried out in these rocky rooms in a sort of process designed to reactivate and re-signify them. During the waiting time before the ingestion, the participants heard a sound work that explained, in a meta-referential and semi-fictional way, certain facts concerning the history of the building and the communities that inhabited these mountains, and concerning certain individuals who would have identified rocks beneath the building and would have eaten them. In the story, past, present and future were entwined and the action that hadn’t yet taken place was described as a previous fact: ‘It doesn’t matter if it was 20, 100 or 200 years ago because the future is not a place. … I think that what they wanted to do was to swallow the mountain, to literally have the stone inside their stomachs and break any kind of immunity they had to its influence. I think they ate it.’ After converting the stone into sand and dust, participants drank the mixture down with firewater.

The second – aerolitic –stone-eating session in which Blanca Pujals, Karlos Gil, Belén Zahera and José V. Casado also took part, was held in 2014 in what had been Barcelona’s main food market, El Born, now a stone mausoleum since an important set of ruins was discovered under its floor. On this occasion, as a way of re-signifying our relationship with stones, borragán organised the ingestion of a meteorite, a rocky chondrite older than the Earth itself. José Vicente Casado, a self-taught palaeontologist internationally renowned for his knowledge of fossils, meteorites and minerals, provided them with the specimen they would consume. At that time, Casado was only aware of there having been two documented ingestions of meteorites over the course of history, one in Russia in 1886 and one in Uganda in 1992, so they thought that that one would be the third.

Litofagos: ærolito. Barcelona 2014.

A hundred-odd people gathered by night at the market, and in a semi-dark room listened to a beautiful long science-fiction story by artists Gil and borragán, which described a palace, stones, craters and creatures who discover that they live embedded in rock. The text is filled with poetic and suggestive images: ‘Then the world burnt. The fire began in the sky while the animals ran inside; after the fire had passed, a crater; an abandoned body that preserves the graphic symbol of the place where the rituals were held, a fossil of experience that demands its proportion, a fabric of stones fallen from the Tree of Knowledge. … We had become rocks in time, ultraviolet pieces of fruit that tried to adapt to a medium in which the ritual resembled the form. Where the rock was eaten as a way of connecting with the future learnt or inherited from ancient times.

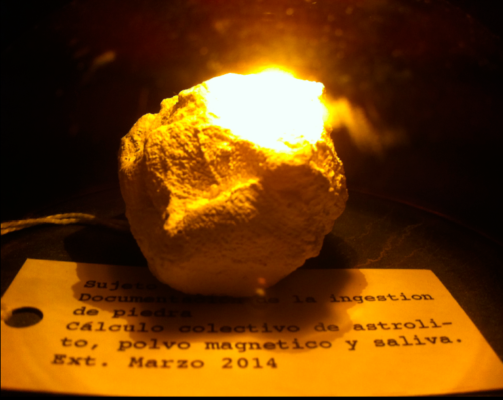

Exhibited in a display case in the same room was a collection of approximately a hundred and fifty bodily stones, both human (like kidney stones) and gastroliths from animals’ bodies. At a given moment, the participants moved to the other side of the room that had until then been concealed by a curtain, where they discovered a few people around a table who proceeded to transform the lunar meteorite into dust using tools and a range of utensils (bowls, hammers, mortars). The active audience also took part in the process, and helped grind the stone. Then the participants were served the meteorite sand mixed with carbonated water, and they ingested it. Besides conventional ways of documenting the event, such as photographs and videos, in this case there was an absolutely unique documentary object, the ADN stone, made out of remains of stone and saliva of the participants, centrifuged with a binding agent.

Exhibited in a display case in the same room was a collection of approximately a hundred and fifty bodily stones, both human (like kidney stones) and gastroliths from animals’ bodies. At a given moment, the participants moved to the other side of the room that had until then been concealed by a curtain, where they discovered a few people around a table who proceeded to transform the lunar meteorite into dust using tools and a range of utensils (bowls, hammers, mortars). The active audience also took part in the process, and helped grind the stone. Then the participants were served the meteorite sand mixed with carbonated water, and they ingested it. Besides conventional ways of documenting the event, such as photographs and videos, in this case there was an absolutely unique documentary object, the ADN stone, made out of remains of stone and saliva of the participants, centrifuged with a binding agent.

Perhaps of the three actions carried out so far, this is the one in which the connection between these acts of ingestions and photography, the artistic discipline in which borragán trained, becomes more obvious. ‘I know it sounds strange – he says – but I still consider my art work as a photographic practice. When we eat exogenous bodies, our tissues are permeated by strange information that modifies them in a process that resembles that of photography.

Litófagos is also, in itself, an exogenous work that is set within the limits of artistic practice in order to radicalise it, surpass it from its marginality and provide an experience that transcends form and concept to enter the mystical and the magical. Like many radical proposals, it brushes ethical and legal limits. The artist is aware of these frictions and, in connection with this work, defends the concept of desecration in the sense given it by Agamben, as an act of restitution that restores to men’s everyday use something that had previously been taken away from them. His work also invites us to think of geophagy as a form of knowledge that emerges before something that cannot be understood from a rational perspective, something that escapes our ‘civilised’ self and demands an extreme approximation. From this point of view, the work of alfonso borragán invites us to think of the buccal-digestive system as a device for learning about the world, and to understand digestion as a form of comprehension that transcends reasoning and eliminates the distance between the subject and the object of knowledge, between the human and the mineral, the mouth and the stone.

Note by the author: throughout this article, the name of the artist appears in lower case by his express wish.

Cover image: Litofagos: Daguerrolito. Collective ingestion of silver. Zagreb, 2017.

Alexandra Laudo is an independent curator. In her projects she has explored, among others, issues related to narrative, text and the spaces of insertion between the visual arts and literature; the cultural history of the gaze; practices of resistance to the image in response to hypervisuality and oculocentrism developed from the visual arts and curatorship; and the 24/7 paradigm in relation to sleep, new technologies and the consumption of esimulants. Laudo has explored the possibility of introducing orality, peformativity and narration in the curatorial practice itself, through hybrid curatorial projects, such as performative lectures or curatorial proposals located between literary essay, criticism and curatorship.

Photo: Foto: © Ernest Gual

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)