Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

The first emoji were created in 1999 by Japanese artist Shigetaka Kurita and rumour has it that they became popular before the need to maintain the subtleties of Japanese social etiquette such as the small bow in conversations mediated by technology. The 176 original emoji by Kurita now form a part of the permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, but before that, thanks to their popular use on mobile phones, the emoji language had already reached each and every corner of the planet to become a language of global use.

In 2015 the Face with Tears of Joy emoji was chosen word of the year in England. All the newspapers filled with headlines because, for the very first time, a pictograph had been crowned as Word of the Year by the Oxford Dictionaries, no less. Regardless of what the compilers of the Oxford Dictionaries might think or allow, there’s something incredibly gratifying in the use of emoji that transcends the implications of their possibilities as a reaction in terms of the economy of language. Yes, emoji are a system that has given us colourful alternatives to tedious replies such as ha ha ha, yet they owe their success to the fact of making it easier for us to express our emotions and understand those of others in connected environments where we can’t look into each other’s eyes or read the signs of our body language.

In 2015, besides the legitimacy of the English academy, the emoji system also ‘updated diversity’ by adding five new tones of skin and a series of gay and lesbian couples. Emoji have entered our daily experience and are here to stay, while their users continue to ask for more little yellow faces since not everyone feels they are represented by the universal design. The context of their use since Kurita presented his first set of emoji in 1999 has changed radically. Their design is now more sophisticated and their use has multiplied worldwide, so that other practices, needs and cultural idiosyncrasies have gradually been introduced.[1]

All these things are especially interesting in the field of user experience (UX), that non-place where the interaction between three elements – the user, the system and the context – is observed, analysed and theorised. Following this common vision, UX has been defined as a consequence of the internal state of a user, the characteristics of the designed system (in this case, the emoji system) and the context in which the interaction is produced. The social and cultural context of the interaction also plays an important role in the impact of the experience, because the user experience may change when the context changes even if the system itself doesn’t change.

Let’s say, for example, that a girl sends the emoji of the flamenco dancer to a female friend in response to a photo in which a third girl is dancing. The context of the reading of this interaction will be different if the three friends are discussing some snapshots of Seville’s April Fair, or if the picture is that of a drunken girl at a wedding in the United States where the guest is dancing like Rosalía, for instance. Now imagine that the friends are gypsies. You thought these three girls were white, because whiteness is automatically constructed. The experience in each context of use is different.

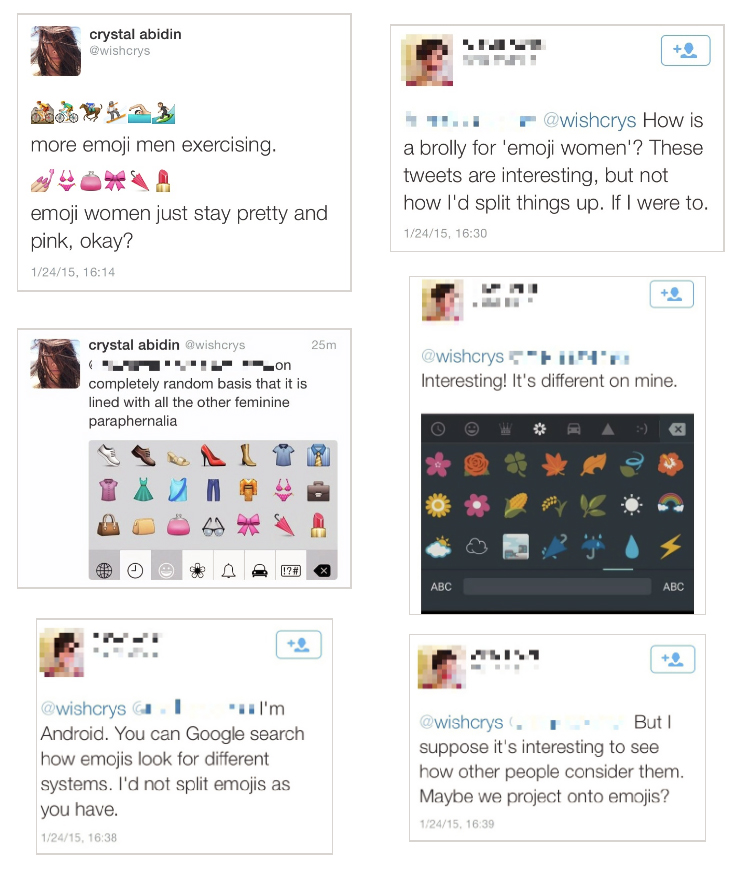

At the end of January of 2015, Crystal Abidin, one of the most leading researchers in social media, compiled a series of observations in her blog on ‘The experience of being “lost in translation” and negotiating on the user experience and the subjective meaning of emoji’. Among her findings were the following remarks, all of which are predetermined constructions of femininity and masculinity:

Emoji men have jobs. Emoji women have expressive hands.

Emoji men grow old gradually. Emoji women grow old overnight.

Emoji men exercise. Emoji women remain pretty and rosy.

Emoji Epistemology

Posted on January 24, 2015 by wishcrys

Crystal Abidin

https://wishcrys.com/2015/01/24/emoji-epistemology/

Later on, in 2018, Crystal co-edited a special issue on the uses and impacts of emoji in the los domains of culture, race, language, art and trade where these initial reflections are packed with theoretical, methodological and analytical solidness in an issue painstakingly published bearing in mind the broader sociocultural implications of emoji and the various forms in which emoji negotiate and mediate the tenuous limit between art and the application. The emoji theme could fill an entire volume, at the very least.

In another article entitled ‘Modifying the Universal’ (2018), Roel Roscam Abbing, Peggy Pierrot and Femke Snelting reflect on the implications of emoji skin tone modifiers. The predetermined universal skin tone marks that which moves towards or away from that which has been legitimated and validated as ‘normal’, classifying everything else as a variation of the normative. Could we possibly imagine a system in which the predetermined skin tone is the darkest black? Could we think of any such example? The female researchers who signed the article on emoji skin tone modifiers wrote that the process of implementation of emoji modifiers presents race, gender and technologies in a way that seems to exemplify how identity policies are becoming a cultural problem, a technical challenge and a commercial asset.

Besides emoji, the debate about how certain technologies foster or express racist attitudes like the digitalblackface isn’t new. It emerged when Snapchat created a Bob Marley filter and when someone decided to use racist codes in their animated GIFS because they found it extremely funny. On such occasions, there’s not much discussion beyond the idea that freedom of speech should also protect racist expressions.

From the point of view of our characteristic whiteness, we find a little harder to understand the fact that some of our colleagues ask us to stop using and overusing black characters in our usual replies with GIFS, because that too is digital blackface. The whiteness that doesn’t see colours sees possibilities of expression and asks ‘What about emoji? Can we use emoji?’ Writing about people who don’t see colours, activist and author Desirée Bela-Lobedde says that there’s nothing wrong in admitting the existence of races (or of people of different colours), and that the problem arises when you discriminate against the people whose colour you prefer not to see. She also says that if you don’t see races, you don’t see racism either. And in that case we do have a problem.

In contrast with the recognition that design isn’t a neutral or unbiased tool and, moreover, it is often a place where racist and sexist standards of normality we have completely internalised easily arise, without too many frictions, the practices of Design Justice appear as a cohesive nucleus of feminist and decolonial design proposals and as a creative and analytical tool to help us tackle structural inequalities we have been suffering for centuries as a society.

Design Justice Network (DJN) is indebted to the Allied Media Conference, an event in which individuals, collectives and organisations working with new media have historically united – the conference has been organised in Detroit for more than two decades – to imagine, create and learn about tools that can be useful for obtaining fairer and holistic solutions. The little seeds of ideas on Design Justice have spread across the world and have become established as a community and a social movement to practice fairer design, assuming a greater degree of responsibility and attention to the context and its implications, over and above intentions.

One of the places where DJN has taken root is Barcelona, emerging in two events held in the setting of the biennials dedicated to philosophy and science staged in the city in 2018 and 2019, leading to the Acción Política + Design Justice fanzine published by Liquen Data Lab. Female colleagues from Madrid attended the events, combining their efforts to shape a project of continuity and launch a proposal from the Mediterranean context. During the summer of 2019, the idea of organising an encounter of Design Justice Mediterránea was conceived and promoted in order to arrange a physical meeting with members of the network in North America, that was finally held in October in the framework of the Internet Festival in Pisa. Thanks to the support and attention of the network, the group was warmly invited by the beautiful Villa Lazzarino to build collectively and caringly the foundations of a new node of activists for critical design in the Mediterranean region.

The Mediterranean perspective, proposed collaboratively, intended and still intends to claim an identity around this geography through a series of assertions. In our present political climate (particularly as regards migration), we intend to dissent from narratives of development and from the global north/south. We intend to generate critical and creative practices to design processes starting from what is already working locally throughout the region. As a part of our process, we intend to be vocally critical of the concept of Europe as a fortress and a monolithic entity. We recognise different routes towards innovation, challenging the dynamics of power that establishes neighbouring Mediterranean regions as a backward, slow and powerless cultural environment, especially after the financial crises of the past decade. We believe that even though in many Mediterranean contexts culture is considered monolithic, culture is inevitably an intense and poignant concept.

After the Pisa meeting, in the month of November a Design Justice Lab was organised in the heart of Barcelona’s Smart City Expo under an initiative of the Sharing Cities space. In a critical exercise, the principles of Design Justice were applied to several booths on the premises using the flyers heaped up on the tables of each one as objects of analysis.

During the session, participants noticed problematical smart city technologies such as cute robots for lonely elderly people, CCTV surveillance designed to improve public transport and ‘housing solutions for migrants’ that I dare say will soon be advertised on Twitter by means of the 🧕🏽👦🏽👳🏽 emoji.

Researcher Terri Senft, one of the most expert voices on the role of the affections in digital ecosystems, has reflected on the links between our emotions and digital lives, advising us that if we understand the combination of individual vision and the social touch as a personalised feeling and as a result of social, technological and biological forces, we are moving from phenomenological space to the realm of ethics, moving away from the question of what things represent towards that of what they are doing with us and for us, and how we are responding.

References

Roel Roscam Abbing, Peggy Pierrot and Femke Snelting, ‘Modifying the Universal,’ Executing Practices, 33, 2017.

Crystal Abidin and Joel Gn, ‘Between Art and Application: Special Issue on Emoji Epistemology,’ First Monday, vol. 23, no. 9, 3 September 2018.

Sasha Costanza-Chock, ‘Design Justice, A.I., and Escape from the Matrix of Domination,’ Journal of Design and Science, 27 July 2018.

‘Design Justice: Towards an Intersectional Feminist Framework for Design Theory and Practice,’ Proceedings of the Design Research Society, 14 August 2018.

Marta Delatte, Alba Medrano, Alejandra Núñez and Sílvia Valle, ‘Acción Política + Design Justice,’ Biennal Ciutat i Ciència and Liquen Data Lab, Barcelona, 2019.

Carine Lallemand, ‘Towards Consolidated Methods for the Design and Evaluation of User Experience,’ Thesis, University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2015.

Effie Lai-Chong Law, et al., ‘Towards a UX Manifesto,’ Proceedings of the 21st British HCI Group Annual Conference on People and Computers: HCI… but not as we know it, vol. 2, BCS Learning & Development Ltd., University of Lancaster, 3-7 September 2007.

Virpi Roto et al., ‘User Experience White Paper: Bringing Clarity to the Concept of User Experience,’ University of Leicester, 11 February 2011.

Terri Senft, ‘From Clickbait to Triggers: Theorizing the Grab,’ Affect Theory Conference, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, October 2015.

[1] An interesting reflection on the differences between packs of emoji is made by Ter in her video La piedra rosetta de emojis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ltAz331p4Nk

(Highlighted image:Original emoji set designed by Shigetaka Kurita in 1999)

Barcelona (1982) Journalist, researcher and consultant at UX with a gender perspective. Co-founder of Liquen Data Lab (www.liquendatalab.com) and of the Mediterranean node of Design Justice (https://designjustice.org).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)