Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Rabat, June 17, 2022

18 rue d’Oujda, 3rd floor

Les Archives Bouanani

I open boxes, leaf through documents, sift through books and magazines.

I am in the apartment of the Bouanani family in Rabat, where Touda Bouanani keeps (and keeps alive) the archives of her parents and sister. A film family. Her sister Batoul was a costume designer and graphic artist. She accidentally died in 2003, the year she turned 34. Her father Ahmed (1939-2011) was a storyteller, editor, writer and filmmaker. Her mother Naïma Saoudi Bouanani (1947-2012) was a costume designer, decorator and production assistant. When I met her in this apartment, she was trying, with filmmaker Ali Essafi, to organize and save what was left of the archives after the apartment fire and her husband’s death. Touda would soon join them.

A film folder. Hadda by Aboueloukar. “In a multilingual country it is strange not to meet more creators who express themselves in several artistic languages. Mohamed Aboueloukar is one of the few who paints and creates films and offers us his extraordinarily rich imagination.” (A. Bounfour, 1982)

This would be his only feature film.

In recent months, Touda, with the group of thinkers, students, artists and filmmakers of the Bouanani Archive, an association created for the preservation and reactivation of this memory of a history of cinema and culture in Morocco, has made great progress in the organization, inventory and digitization of the documents, books, brochures, photographs, posters and archives stored there. There is also jewelry, drawings, costumes, decorations. Comics and albums rub shoulders with books on cinema theory and the history of Morocco, but also with the personal belongings of the family. Artists and researchers-in-residence are welcome. They participate in this collective work.

A book. Dialogues Algérie – Cinéma, Première histoire du cinéma algérien, by Younès Dadci. Published in 1970, it evokes the life of cinema in Algeria from 1896 to the present day: “To better understand current Algerian cinema, we have to go back.” I imagine that this reading surely inspired Ahmed Bouanani for his History of Moroccan cinema, which remained unpublished until very recently (La Septième Porte, une histoire du cinéma au Maroc de 1907 à 1986, Kulte éditions, Rabat, 2020).

Along with Dadci’s book, a DVD of the legendary Algerian film Tahia Ya Didou by Mohamed Zinet, Editions Tassili. Zinet also directed only one feature film.

The Bouanani collective tries to recompose, fragment by fragment, a history of cinema in Morocco that is barely known. These documents, which time, fire and water have weathered and weakened, must be taken care of and repaired. Touda set up a small book repair shop in a bedroom.

The archive contains scars on its material: damp halos, yellowed or burned leaves, inks diluted in the water that had been used to extinguish the fire when the apartment burned down.

A review. Tricontinental. No. 2. A blue stamp indicates December 28, 1967 on the first page. This is the OSPAAAL newsletter,

Executive Secretariat of the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America.

In each of my experiences with the apartment archives, new items appear. New links are made. Each fragment of this archive allows us to better understand it, capture it, let new constellations appear, to better understand the circulation of the ideas, forms, aesthetics of the time. Today, documents are organized and stored in archive boxes. Colonial Cinema. Moroccan Filmmakers from A to Z. The Structures of Cinema in Morocco. Correspondence. Manuscripts. Magazines. IDHEC.

A letter. 1969. Written to Ahmed Bouanani by the Greek filmmaker Tonia Marketaki. They studied together at IDHEC. “Well, here I am doing in Algeria doing the kind of work that I would have liked to do in Greece after I came back from studying, but which conditions in Greece did not allow me to do.”

What this archive tells us are both the hopes, the dreams, but also the efforts and the work carried out by these filmmakers “for a Moroccan cinema.” In the 1960s (some even earlier and others later), these young filmmakers and technicians, often trained abroad, returned to Morocco determined to create a new cinema for their country. They wanted to decolonize culture and reappropriate a long-confiscated narrative, after so many years of colonization.

Lamalif magazine. Press releases. From 1969 to 1982. Moroccan cinema in search of lost time. Cinema in Morocco yesterday and tomorrow. When filmmakers mature. A thousand and one hands, a new stage in the painful evolution of Moroccan cinema. Moroccan cinema: a problem to be solved. Obstacles to the emergence of a film industry. Something new for filmmakers. Producing movies? And after that?

The reports, letters, files, administrative documents, manifestos, notes, drawings, all these elements preserved in the Bouanani Archive testify to the desire to organize collectively, to create associations of filmmakers, to campaign for the existence of a national industry capable of supporting them in the production and distribution of their films, to create festivals, to demand the existence of a fund to help filmmakers, to find pragmatic solutions to realize their dreams in the face of the obstacles they encountered. The hope was great, as was the collective energy.

A magazine. It is not yet inventoried but it is placed on a shelf in a room, between an issue of Jeune Afrique from the Festival des Arts Nègres de Dakar (1966) and an issue of Miroir Fantastique entitled Les superhommes entre nous. Politique Hebdo, Thursday March 11, 1971, number 23. Price 3F. A pink blanket. The last burners of colonial France. Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin: What to do in cinema. “Making a film is, thus, also participating in the struggles to organize in a new way.”

The archive is incomplete. The fire, of course. But also because it contains mostly texts written in French, while many texts on cinema are in Arabic. It doesn’t try to be complete. It was formed based on friendships, collaborations, interests and experiences of the Bouanani family. It is organized above all around the research carried out by Ahmed Bouanani to write his book on the birth of Moroccan cinema, La Septième Porte, une histoire du cinéma au Maroc de 1907 à 1986, published by Editions Kulte in 2021, which required many years of data collection.

A small, decorated notebook. Writing on felt, words in red, others in blue.

Moroccan television presents

LETTER FROM IMILCHIL

a film by Naïma Saoudi

We haven’t found this film yet. We hope it is in the Moroccan television archives and will reappear one day.

Navigating through these documents, opening the catalogs, the newspapers, the production archives, we realize that the history is incomplete. The narrative is fragmented. It is the history of a cinema interrupted by a series of erosions, oblivions, erasures and disappearances. Movies that have been lost, censored, banned, never made, prevented. Aborted careers. Forgotten stories.

A press clipping. An article. “Unfortunately, Moroccan filmmakers live only in projects. Nothing more. This is the common evil of our generation. This year I am finishing a short film entitled Sidi Ahmed or Moussa that allows me to reconnect with the mythical reality of the past. Studying 10th century Hegira (16th century in the Christian era), the time of the Portuguese occupation and of the great poet Sidi Abderrahman El Majdoub, I find strange affinities with the current reality that we are experiencing. To reconsider the past is to understand the present in order to dominate it and to find the weapons needed for our defense and survival. There is no better project for the future than to participate by small means in the radical and systematic transformation of society for the construction of a world that is not traumatic. Ahmed Bouanani in Nourredine Sail, Rabat Maghreb Information, 1973

This film would never be finished due to lack of support from the Moroccan Cinematographic Center. There is no hurry.

The dreams of these young filmmakers seem to be shattered by the official vision of the society, politics and Morocco desired by the State and by the colonial institutions that endure. Despite the immense hope born of independence, and the media that seemed to support the birth of a national cinema, this will be accomplished only by struggles, personal and collective, often difficult and also often forgotten today, just like the formal avant-garde proposals of the time that had emerged. Each of these stories is essential. The history of cinema cannot be limited to films made, and even less so of films screened. It is necessary to bring utopias, dreams, failures, impossibilities, including those that never existed, what was desired and imagined, what was left on the margin.

On a shelf, the four issues of the short-lived CINEMA 3 magazine edited by Nouredine Sail in 1970. A dossier on Brazilian cinema. Cinema according to Ousmane Sembène. An interview with Ferid Boughedir. “ANTI-CANNES”, the title of an editorial in the third issue: “The Impressed Film Monoprix awarded its 1970 grand prize to the film that best meets the artistic criteria of bankers, speculators and fashion merchants.” “Of course, there were oversights. The Land of Youssef Chahine has the flaw of being Egyptian. Elise or Real Life by Michel Drach was considered too long, too slick. And then, whatever we say, Algeria is behind. In spending..” adds Nourredine Saïl. On the last page of the second issue are letters by the readers: “Cinema 3 is the first Moroccan film magazine that deals with the issues and problems that matter.” On page 57 of the first issue of Cinéma 3, in an article entitled “Waiting for Karim,” the shooting of Les enfants du Haouz is discussed, an observation on the life of rural youth and their problems, by Idriss Karim. “We promise our readers an interview with I. Karim as soon as the film is released on Moroccan screens. Very soon, we hope.”

The fifth issue of Cinéma 3 magazine was confiscated and there would be no others. The film Les Enfants du Haouz was re-edited and then banned. Now it’s gone.

By traces, a story of desire, struggles and dreams, often revolutionary, like the dreams of cinema, appears to us. Faced with these hopes, situations that are repeated, that put the filmmakers to the test, that take away their strength, that annihilate the groups, that divide. As if the State were struggling to extinguish the flame of their creativity, dignity and potential subversion, to achieve their submission. Situations that are repeated.

A CV of Abdellah Drissi (born in Rabat in 1941), who won the “Diploma of the Lodz National Film and Television Theater School, Very Good Mention,” and whose film Lesson 41 received the first prize for best film documentary at the Warsaw Film Festival in 1967. He never became a filmmaker.

These multiple archives are inhabited with lives, voices, complexities, potential stories, singularities, circulations, fragmented and non-linear narratives, exploited narratives. When carrying out research, archiving and restoration projects of cinematographic narratives, it is necessary to appreciate these archive spaces in their complexity and not come looking for a fixed meaning, but rather to allow multiple voices to unfold. I keep reading.

A shooting script. Une breche dans le mur by Jilali Ferhati. Cinematographer: Ahmed el Maanouni. In this document, which is developed in large format, we can read the list of actors, their roles, their shooting days, the sets. Malabata. Café Hafa. Inspector’s Office.

Are Jilali Ferhati’s films really lost as they say? A Breach in the Wall is a film that urgently needs to be restored.

Why attempt to archive what is absent? Because there is, and always has been, and still will be, a rejection of counter-histories, a refusal to let society and history be written in any other way than by the voice of the dominant, a refusal to see and accept the most radical writings in the world that these committed filmmakers proposed, engaged in aesthetic, intellectual and political struggles. We need an archive of these prevented radicalisms. We need to fight so that these counter-narratives can continue to emerge today.

A photo from the shoot. Leila Shenna in Chergui by Moumen Smihi. The Moroccan actress had a career in her country and internationally in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. She has acted in the films of the Algerian Lakhdar Amina and in Bertolucci’s Ramparts of Clay. She also played a “Bond girl” in Moonraker.

Then she disappeared. No one knows where Leila Shenna is today, despite an intense investigation to find her carried out by the filmmaker Ali Essafi.

How can we bring these uncertainties, these tests, and these trials and errors into our cinematic stories?

How can we preserve films that don’t exist, that were prevented or damaged by political histories, lost in the margins of the dominant film industries and geographies?

How can they be summoned by their absence?

Can we use film restoration techniques to preserve the traces of what is absent?

What place can be given to fiction in this work of political and aesthetic recomposition?

How can we guarantee that no future film programmer or historian will write history without taking into account this cinema in all its complexity?

What future can we imagine and propose for these films based on their traces, their scars, and the voices, stories and lives that inhabit them?

Can we restore and reactivate the desire for cinema and the dreams of revolution carried out by young filmmakers in the 1960s and 1970s? Can we invent new spaces for our future?

What if the archives were these spaces of reinvention?

What archives can we invent for our future?

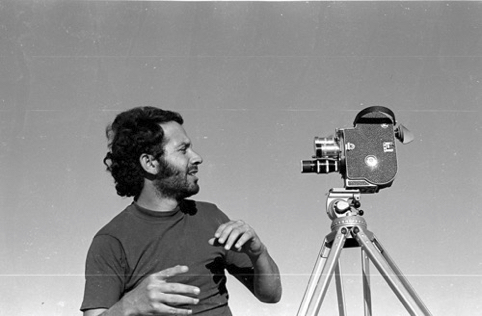

(Featured Image: Mohammed Abbazi in Erfoud, 1970, by Susan Woolf)

Léa Morin is a curator, independent researcher and programmer. She is particularly interested in the circulation of ideas, forms, aesthetics and political and artistic struggles, as well as the challenges of preserving the film archives of weakened, minority cinemas and struggling against authoritarian narratives. She is a member of the Archives Bouanani team: a history of cinema in Morocco (Rabat) and of Talitha (www.talitha3.com), an association committed to the re-circulation of sound and film works through publishing and catering (Rennes). In particular, she worked on the restoration and recirculation of Mostafa Derkaoui’s first film “De quelques événements sans signification” [Some Events Without Meaning] and designed the archive website www.cinima3.com dedicated to the story of the passage of Moroccan filmmakers in Poland in the 1960s and 1970s. She was director of the Cinémathèque de Tanger.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)