Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Robert Heinecken is becoming a badly kept secret – although still relatively unknown, signs of his (re)discovery appeared last winter when Artforum and Kaleidoscope almost simultaneously published texts proposing Heinecken as a forefather of the Pictures Generation.

Along with John Baldessari, Wallace Berman and Ed Ruscha, the Denver-born Robert Heinecken (1931-2006) began working in California during the 1950s, and like his contemporaries shared an interest in using photography in new ways. Unlike the prevailing belief of the time that images were original representations of reality as expressed by their maker, Heinecken used pre-existing images, thereby giving up authorial control, proposing that arrangement could endow images with new meanings. In fact, Heinecken did not only appropriate images but went even further by photographing existing pictures. Working with his own personal collection of photographs and using print transfer techniques, he was mainly concerned with the abundance of images in a society that was becoming both more technological and more consumerist. Heinecken said that images rather than being “pictures of something” were “objects about something”, thereby opening up a reflexion on its materiality and ways of existence.

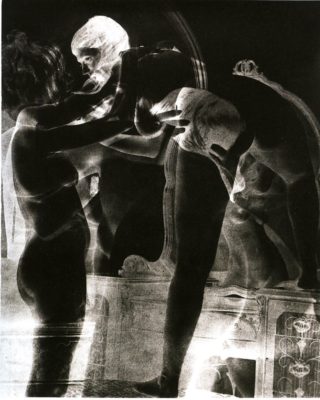

Heinecken’s concern with materiality and modes of circulation of pictures was highlighted at a recent exhibition at Geneva’s Mamco in a rather small yet dense display. Related to Periodical #5 (1972) on view, is typical of Heinecken’s working method that consisted of overprints of images extracted from magazines that could be said to be like the meeting of recto and verso. In this work, an image of a woman from the armed forces smiling while holding decapitated heads in both her hands is printed over an article about birth control and an advertisement for a hair loss tonic. Here, sarcasm is Heinecken’s tool of choice for interrogating the co-existence of these very different types of images and messages. The similarity in their original framing and appearance implies that the way in which they are consumed is also similar, their meanings strangely belonging to the same realm — information and publicity as the same kind of entertainment.

Robert Heinecken talked about commercial images as manufactured experiences. Lessons in Posing Subjects (1982), also on view at Mamco, is a series of Polaroid snapshots of fashion and lingerie models arranged according to the type of pose, accompanied by an instructional text explaining what they suggest, describing every possible variation of the image. Although this series evidently points towards the standardising of behaviour as formalised by advertising, the specific use of Polaroid, the hallmark of personal photography at the time, brings the work into the realm of a more subjective everyday. The images speak about the replacement of personal recollection with preconceived stereotypes but Heinecken’s tone is neither didactic nor pompous lying instead somewhere between fascination and mockery, recalling Richard Prince at his very best.

Heinecken’s double investigation, on the one hand into constructed desire and on the other into the modes of image circulation, make him a likely contender as the foremost influence on the generation of artists born between 1945 and 1955 (Barbara Bloom, Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, amongst others), who continued to work with this approach throughout the late 1970s. Although Heinecken’s role and influence is still subject of speculation, there is no doubt that he will finally be granted his rightful place in art history when the upcoming survey of his work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) opens in March 2014.

François Aubart reads and writes on whatever topic that can triggers him to reinterpret – a state of mind he sometimes use to curate exhibitions and talks about with his friends when editing an issue of journal Δ ⅄ ⚙

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)