Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

“Take a look, it’s not just in the museums that there’s shit.” ROBERTO BOLAÑO, ‘Leave it all behind, again’.

An exhibition for a literature-sensitive audience: Bolaño Archive (1977-2003) . After leaving the show curated by Juan Insúa and Valerie Miles at the Barcelona Centre for Contemporary Culture (CCCB), which is on until 30 June, I feel the urge to rearticulate what I’ve just experienced. The Bolaño Effect.

The writing in the margins as opposed to the idea of the centrality of the book is the pivotal axis that is redefined in this exhibition. The layers of text are what matters, perhaps more than the final result; probably because we have the nucleus, i.e. Bolaño’s books, within our reach. But all the prior condensation of information that builds up the long path trodden by him connecting ideas and creating (constructing) stories, resides in a heritage of readings and references that until now have been unknown to readers. The opening up of the archive in this first exhibition resituates the author’s working spaces and shows the veiled dimension of his “quasi detective” side. The one that most captivated me, while walking round this laboratory-turned-exhibition event, is the vitrine with the lists of revolvers, crimes and phobias:

Ergophobia: fear of work

Thalassophobia: aversion to the sea

Panophobia: fear of everything

Peccatophobia: fear of committing sins.

In films there is the script, a storyboard for filming that details each individual scene; in Bolaño’s work there are lists of descriptions, bits of complementary information and personal notes. It is the preparatory chronicle for the setting up of the story. A geography, of locations and characters, constructed on solid foundations but not for this deprived of the freedom of growing during the reading time.

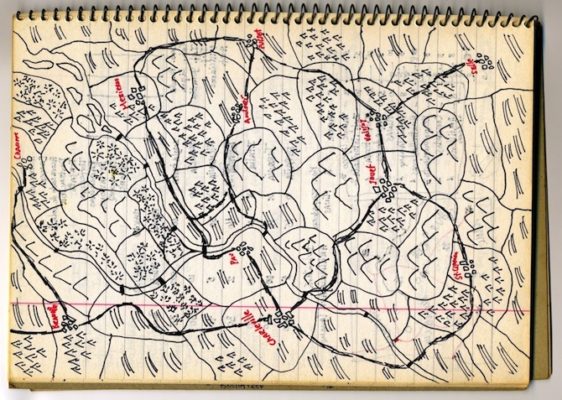

Research highlighted with drawings that the author himself made in his diaries to code the entries; long footnotes to extend the scenes of the writing. The curators take advantage of this resource to suggest to visitors that they play a “detective game”; in other words that they follow a series of clues. The clues themselves are signs that emulate the symbols used by Bolaño to highlight something in his notes: glasses with eyes to indicate the value of the paragraph, a five-point star or a head with long hair held up by a hand. There is a whole series of these icons that the audience, invited to metamorphose into investigator, has at its disposal.

I find the incitement to become clue-followers unnecessary. Although it is not an imposition it really affects the reading. These marks that appear in the manuscripts and notebooks are highlighted in the vitrine. The playful aspect is already present in Bolaño’s writings and it seems to me that with the enormous amount of material in the room, the readers have plenty to be able to immerse themselves in his ways of working. Let’s not forget that irony and humour form part of Bolaño’s literature. That is why I insist that the nod and wink towards the signs is excessive in an exhibition that provides a masterful and yet official look into Bolaño’s life and archive.

The thanks to Caroline López, the writer’s widow, for both protecting and cataloguing his legacy is both public and relevant. But allow me to raise an eyebrow and a suspicion: the fact that she classified and selected what is on display in the exhibition also establishes a multi-layered filter. Today we know what she wanted to show us and how she has systematised and crystallised the archive according to her criteria and wishes. Why deny it? I would like to know what she left hidden or in the wings to be revealed on another occasion. We will have to wait for another outing of the inventory of notes to the museum. And what will happen meanwhile to the archive in the custody of the heirs? How can we gain access to it? In any case, this first step is an important, particularly if we don’t pay too much attention to the fetishistic touch of displaying the typewriters, the glasses, the computer, etc.

I stop here in the knowledge that I could say more, but a bit of self-criticism never goes amiss: the last word is that of the reader and the person who looks at the exhibition, which is certainly a great event. Boloño himself gave a warning in this quotation which also serves as the closing piece: “Don’t believe the critics, read them if you must, but don’t believe a word of it“.

An incurable onlooker, Aymara Arreaza R. uses walking around, reading, the criticism of displacement and questioning as her working tools. She is a hybrid of trades: expressing herself through writing, some of her own images, teaching as well as research projects that she backs up with the construction of more personal geographies. Since 2011 she directs www.rutadeautor.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)