Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

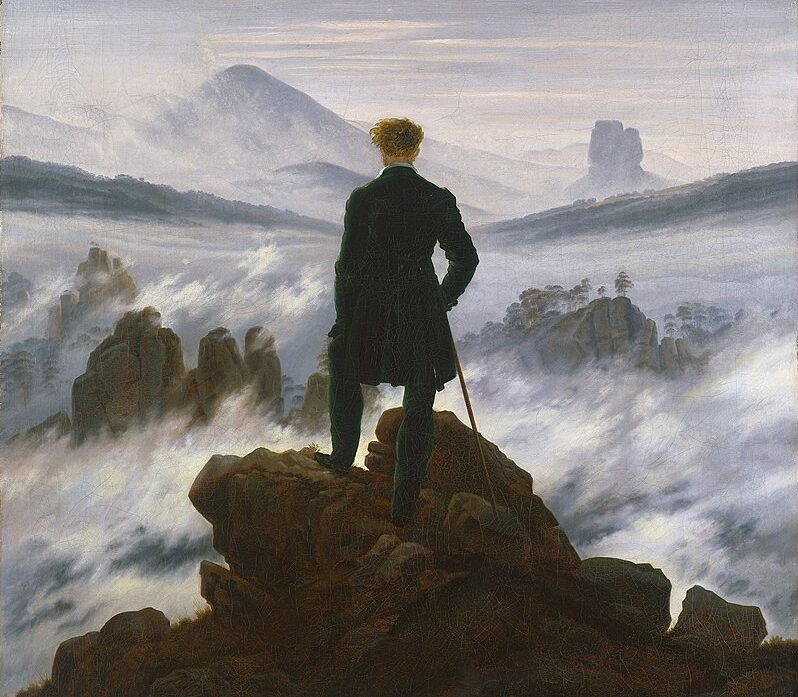

Caspar David Friedrich, in his painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818), offered us one of the most iconic images of the relationship between the individual and nature.

Friedrich’s Wanderer is depicted as a man standing firmly on a mountaintop. This image fits perfectly into the tradition of Western art, in which the individual contemplating nature is typically male, white, and able-bodied. The Romantic hero is defined by his physical ability: he has climbed the mountain, overcome obstacles, and now dominates the landscape as his gaze connects him to the infinite

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

This “able” body fully reveals its tools of domination and becomes the implicit norm through which the relationship with the world is defined.

If we imagined a wanderer with a different body, perhaps with a prosthesis or using a cane, not only as a symbol but as a necessity, or in a position that did not allow for visual dominance over the landscape, the interpretation of the work would change radically.

In an attempt to subvert this interpretation, we can imagine a painting that represents the sublime not as a privilege of those who can “reach the top” but as a universal experience that manifests itself in diverse ways, such as a wanderer who faces the landscape with a non-normative body or someone who experiences the sublime without needing to “climb.”

The sense of silent and contemplative triumph would be transformed into a reflection on bodily presence in space and on the barriers, visible or invisible, that define who can or cannot access such an experience.

What Friedrich clearly conveys to us is that art, as commonly understood, is an intelligible and complex language which, by its nature, is a very elitist space, one in which normative bodies mostly operate, both as a public and as a professional.

It is only with our greatest efforts and productivity that we can attempt to reach the highest peak.

Expectations are very personal, dictated by our origins, sociocultural context, experiences, and bodies.

I arrived in Barcelona seven years ago, and for me, migrating meant giving things a new name. It meant embracing my disability and living in a balance between autonomy and interdependence, concepts that didn’t exist in my vocabulary.

I was born with a genetic disease called osteogenesis imperfecta, commonly known as brittle bone disease. Fractures, orthopedic devices, medical ID photos, waiting rooms, hospitals, and recovery time have been a constant, slowing the pace of my life, far from the competition and frenzy of the normative world.

I know from experience that many professionals or non-disabled people won’t accept this, but my body has taught me many things. I’ve never felt the desire to have another and I’ve never thought: Why me?

The first time I realized my body was a political body was when I took self-portraits standing up, without clothes. I was just over twenty at that time. I vividly remembered several moments from my childhood when I was photographed standing up, naked, with my arms open, gazing directly into the camera, while they played at taxonomy. They photographed, measured, and spoke about me as if I couldn’t understand their language, and then they returned me to my mother’s arms.

Taking portraits of myself wasn’t healing. Art doesn’t heal anything, and to think it does is the most welfare-oriented thing normative people can assume. It was, as Paul B. Preciado would say [1] Paul Preciado (2024) Lorenza Böttner, Réquiem for the norm. Spector Books , “reorganizing the relationships between power and the gaze, appropriating a representation, resisting being the object of representation of disciplinary medicine.”

As an artist and educator living in Catalonia, I taught art classes in special education centers for three years. Yes, that is what I do, and I do so by allowing myself to be touched by the violence represented by these spaces of exclusion. These are places from which I had accepted their disappearance, having been born in Italy after 1977, the year Law 517 came into force. This legislation, the result of Franco Basaglia’s struggle, set a precedent by establishing the definitive elimination of special schools and special education, thus affirming the right of children with disabilities to grow up in an all-exclusive school.

My first challenge was to dismantle the approach to art education as something technical, institutional, and manual, which limits students to follow precise instructions [2]Suárez Vega, Á. (2021). Educación, arte y enseñanza: ¿Para qué la educación artística? Voces y Realidades Educativas (Education, Art, and Teaching: What is Art Education for? Voices and … Continue reading. As María Acaso argues [3]Acaso, (2016). La educación artística no son manualidades (Art education is not crafts). Catarata, “we must reject crafts” , support bodily and personal expression, and focus on desire, which begins with sexuality but expands to more invisible issues, such as self-knowledge and simply daring to express personal tastes and ideas. These are essential actions to respond to a society that silences bodies outside of established norms.

Claudia Ventola

The second major issue was to draw new lines to create historical references, embrace the self-imposed disciplinary limits of art, and understand how the ableist gaze mimics and always shapes itself in favor of the supremacy of normativity.

Ableism isn’t only manifested in the lack of representation of bodies with functional diversity, in the glorification of the perfect body from Greco-Roman statues to Renaissance sculpture and Social Realism with its pieties, to the fetishization of the disabled body. It is also seen in how we interpret artists whose life trajectories were marked by a particular condition, omitting or emphasizing it as the case may be, but always perpetuating a perspective that dissociates the artistic value from non-normative corporality.

The question is: When will we truly consider the potential of disability to alter the cis-normative and ableist hegemonies that exist? This isn’t just a question of identity, but rather a question of what disability contributes to our understanding of the world and to the violence we experience.

I remember one day when a 13-year-old boy, born with cerebral palsy, made me understand complex things with a single sentence. We were in class analyzing Bruce Nauman’s work Dance or Exercise on the Perimeter of a Square and he said: “I understand this work because it took me a long time to learn how to walk and to be in things.”

From the theoretical perspective and in art spaces, the phrase “putting vulnerability at the center” has been preached for years without knowing specifically how to do it. I bring you this example because it erased from my mind the theories and big words we like to read from the heights of academia, returning to something as simple as finding a bridge between our lives and what we have in front of us, what we call art. He put his vulnerability at the center and found the mediation of that work.

Since 2024, the Barcelona City Council has activated an accessibility plan for museum spaces that aims to achieve “universal accessibility.” Physical accessibility, communicative accessibility, and cognitive accessibility are the central axes of the project, which will be in operation until 2030.

To question this plan a bit, I return to the words of Helena Vinent and Tatiana Antoni Conesa: “It’s not about including disabled people through intermittent accessibility measures in a system that disables and excludes us, but rather about questioning the idea of normality and breaking with the ways of functioning to which we are accustomed.” [4]EGAÑA ROJAS, RACCO, G. (2024) Culture isn’t a highway and museums could be gardens.

That is to say that projects that include functional diversity as a critique are welcome, but they are of little use if we are unable to imagine a structural change in institutions without analyzing the system that oppresses and creates disability.

It’s not just about meeting quotas but about challenging the legitimized knowledge of normativity and being able to imagine new possibilities and discourses together.

[Featured Image: credit Sophia Vargas]

| ↑1 | Paul Preciado (2024) Lorenza Böttner, Réquiem for the norm. Spector Books |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Suárez Vega, Á. (2021). Educación, arte y enseñanza: ¿Para qué la educación artística? Voces y Realidades Educativas (Education, Art, and Teaching: What is Art Education for? Voices and Educational Realities) |

| ↑3 | Acaso, (2016). La educación artística no son manualidades (Art education is not crafts). Catarata |

| ↑4 | EGAÑA ROJAS, RACCO, G. (2024) Culture isn’t a highway and museums could be gardens. |

Claudia Ventola. Crip artist and researcher who develops projects that question the continuous redefinition of the political body in relation to the competitiveness of healthcare, the infantilization of non-normative bodies, and medical violence. She generally investigates the poetics of pain as an interference with the rhetoric of triumph of neoliberal capitalism. She currently collaborates with E:\\ART as an artist-educator within the Dialògiques project for adolescents with functional diversity.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)