Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

A text can weave together bits of contradictory writing and present them as a coherent argument.

Writing about screen fragmentation on (this) fragmented screen is the most direct connection possible to the idea of reading (this) text. What mediates between the writing of the text and the reading of it on this website is precisely a divided screen (the parentheses above act as connected windows). And what is proposed here is a fragmented text, contradictory or coherent, for a divided attention (yours) equally fragmented when reading (this/that) text.

++++

Every screen is a fragmentation. The screen inscribes a fragmentary condition in what it presents. The fragmentation of the screen is nothing more than an incidence in the enunciation system of the moving image, its circumstance or its syntax. This formal and/or discursive characteristic is what gives the screen its intended uniqueness, it is what creates a screen-world and, therefore, a world outside of it. Thus, the screen creates a universe in flux that keeps the idea of representation alive.

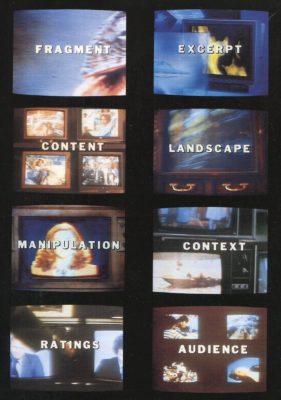

TV Collection (1979’s). Jaime Davidovich

++++

The screen carries the seed of fragmentation, a seed that is reproduced with each new shot as the immediately preceding window breaks apart in our mind. We already drag with us many broken windows, smashed by the incessant activity and derailed development of audiovisual language. Seeds and windows that multiply endemically awaiting the collapse of contemporary audiovisual genetics.

++++

The “Global Screen””[1]Lipovetsky, G. y Serroy, J. (2009). La Pantalla Global. Cultura mediática y cine en la era hipermoderna. Anagrama: Barcelona. is the epitome of this circumstance. “Everything is a screen” because when we look at the world we see only fragments. Audiovisual language has established itself as our vision of the world. It has even taken over the live performance of our nightly dreams. Reality and fiction have been dissolved into non-linear time. The screen remains aloof from our concerns, inhibited by the disruption of the space-time coordinates on which we have built our culture. The screen remains vain and inflexible, admitting everything, merciless before the cracking of the world’s image.

Surveillance cameras

++++

Ask a video game fan about the concept of split-screens and what they tell you won’t be at all the same as a professional who holds videoconferences in his workplace. The division of the screen is a resource that has fragmented itself: as a communicative function, as a category, as a situation, setting or frame of expression. In the divided screen of Fortnite (Epic Games, 2017), corpses of office workers have been found in an advanced state of fragmentation.

++++

What we understand as split-screen belongs to the metabolism of the audiovisual device in its transit towards the general absorption of the representation of the world. The insatiable appetite of its increasingly compact pixel fabric is capable of assimilating all kinds of information. It began by breaking the time and space of action and went on to make possible the coexistence of comedy shows and news tragedies. It assimilated zapping to compose an unprecedented control board of genres and styles, increased their speed and sound and even supplanted background music and street voices. The anxiety of this crystalline, electronic surface is our anxiety, its ability to frame unrest and astonishment is our survival mechanism. Who has not looked at a screen as if it were a mirror?

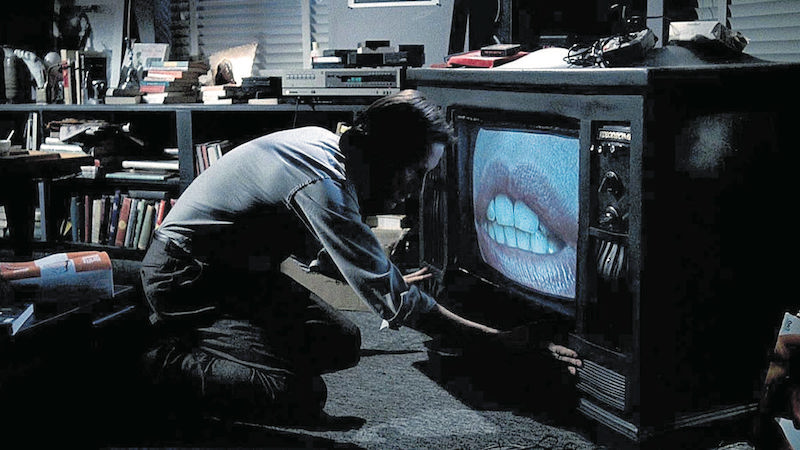

Videodrome (1983), David Cronenberg

++++

The screen is a minefield. We eliminate pop-ups in fps —first-person shooter—, we jump from one topic to another, leaving an erratic trail of drives, emotions, and urgencies. And while the screen multiplies inwards, it engulfs us, just like in the film Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983), taking us to a visual density in which it is impossible to orient ourselves. Our wars and our peace happen inside there. When we wake up, we are walking upon an immense field of broken (split?) screens, the scene after the battle[2]The visual reference for this landscape is found in Hans Haacke’s installation Germania, exhibited in the German pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale, in which he made explicit reference to the … Continue reading.

++++

The search for a comprehensive, complete, enveloping vision is a constant in the visual arts. Leon Battista Alberti led the painters of his time to consider the painting’s frame as an open window. But the windows multiplied, with triptychs, polyptychs, and baroque paintings overwhelming the gaze, “our eyes have always wanted more” and art has sought a way to satisfy them. From Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927) to Tarantino’s Jackie Brown (1997), the use of a divided, expanded or fragmented screen provided narrative possibilities or space-time simultaneities that allowed the story to expand within the mind. But the split screen also allowed us to break down the lines of action of the diegesis to address the perceptual and sociopolitical functions of the cinematographic apparatus. “The division of the senses[3]Rancière, J.(2002), La división de lo sensible. Estética y política. Consorcio Salamanca”, the political dimension of aesthetics, take place within the audiovisual screen in a literal way.

++++

The monitor, taken from the television and coupled to the computer, has been gaining prominence over time[4]For more information on this topic, see “La colonización de las pantallas. Sobre la exposición Pantalla Global”, de Jorge Luis Marzo. Published … Continue reading. Information ceased to be a language to become an image and the world became a watched screen and a screen that watches. Its triumph as manager of the environment, both technical and social, made possible the psycho-technical and biopolitical imaginary that today we have internalized under the name of Global Screen. In this way, the way to power exercised by the image industry was paved by normalizing our servitude, although there are still dissident screens that end up dividing themselves within the dominant screen.

Today, multiple windows coexist and overlap on our computer screens, jeopardizing the perspective on which our visual perception of the world (and also of the arts) has been based. Our window, now open to virtuality, proposes a new logic of visuality, a new architecture not only of space but of time.

Video is tv? (1989), Antoni Muntadas

++++

We watch the projection Video is television? (05’34, 1989) from Muntadas and the first thing that strikes us is the apparent exhibition error that shows a single-channel video piece designed to be seen on television, but immediately afterwards we understand it as curatorial license. We pay attention to the images of Poltergeist or Videodrome and to the concepts that appear, such as fragment and context. We think about what it would be like if it had been projected onto a flat screen or a television like the ones that appear in the video itself. The matter is further complicated when Glenn Branca’s soundtrack accelerates as the television screens multiply towards the end of the piece, a montage device made before the ‘mosaic’ effect of digital editing existed. In one fell swoop we see in the projection the summary of the image’s dissolution in the “flow of life[5]Kracauer, S (1996), Teoría del cine. La redención de la realidad física. Paidós: Barcelona.”, of its conceptual liquefaction in the formal, or its deformation in the conceptual.

Asyl 31/75 (1975), Kurt Kren

++++

In Asyl 31/75, (08’, 1975), Kurt Kren shows on a single screen transformations of a single landscape during twenty-one non-consecutive days spread over a year. A photographic experiment of multiple exposures and segmented images in which time and space overlap and coexist thanks, among other techniques, sticking tape on the lens with holes in it that at times creates the magical illusion of a puzzle to be assembled on the screen itself. With each new shot, the screens add up until we discover a landscape in which the seasons of the year and their different qualities of light coexist, snow, sun, and autumn, and in which the cinematographic form surrenders to the contemplation of time. In this piece, the process is the opposite: the screen is constructed from fragments. The screen becomes itself again, although the image has had to go through countless movements.

++++

Suppose that each of these fragments is opened in a pop-up window and that, by means of our imagination, we can see its reverse side. There are red threads that seem to connect ideas from one fragment to another, woven together with citations and footnotes. But we see that the largest number of these threads are left hanging, suspended, waiting for a link to other ideas and to other references. Clearly, the responsibility for connecting these threads to other windows or screens becomes our responsibility.

(Front Image: Video is tv? (1989), Antoni Muntadas).

| ↑1 | Lipovetsky, G. y Serroy, J. (2009). La Pantalla Global. Cultura mediática y cine en la era hipermoderna. Anagrama: Barcelona. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The visual reference for this landscape is found in Hans Haacke’s installation Germania, exhibited in the German pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale, in which he made explicit reference to the pavilion’s roots in Nazi Germany politics. |

| ↑3 | Rancière, J.(2002), La división de lo sensible. Estética y política. Consorcio Salamanca |

| ↑4 | For more information on this topic, see “La colonización de las pantallas. Sobre la exposición Pantalla Global”, de Jorge Luis Marzo. Published in https://www.soymenos.net/colonizacion_pantallas.pdf |

| ↑5 | Kracauer, S (1996), Teoría del cine. La redención de la realidad física. Paidós: Barcelona. |

Arturo / Fito Rodríguez Bornaetxea is an artist and lecturer in the Faculty of Fine Arts at the UPV / EHU. Collective work, experimental audiovisual, de-commissioning proposals, independent initiatives, untimely actions… (SEAC, RDZ Foundation, Amarika Assembly, Zas Kultur, Tobogán…). Beats against the Institution, slips in the Academy, disagreements and generalised blunders as a trajectory. For years he has understood disorientation as his natural working context. Now, in a flight forward, he has decided to publish stories with the intention of recognising this context from other perspectives.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)