Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Sarrita Hunn and James McAnally founded MARCH in 2020 as an expansion of their previous publishing project, Temporary Art Review (2011-2019). MARCH is an art and strategy magazine consisting of an active online platform and annually paced print editions.

Mela Dávila Freire – Could you briefly describe how you came together and decided to start a project together?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – We met in 2010, when Sarrita was an artist-in-residence at The Luminary, a non-profit art center co-founded and directed by James in St. Louis, Missouri (US). Prompted by a proposal Sarrita wrote in her residency application to start an art criticism website, we began discussions as a set of escalating approaches to a decentralized approach to art criticism, which led to us launching Temporary Art Review in March 2011.

Temporary Art Review was founded to address two related major issues in cultural criticism we identified at the time: the predominant focus on commercial galleries in large urban centers (i.e. New York, London, Los Angeles) and the lack of a substantial platform for critical discussions around nonprofit and artist-run spaces and cultural activities in smaller communities, especially locally in St. Louis. In this way, Temporary Art Review first aimed to become a connector for artist-run spaces and smaller art communities across the United States. After about three years, however, we felt like we had covered a lot of ground in the US and started including international artists, writers and spaces, and more topically driven content.

In 2017, we started discussing the future of Temporary Art Review, which eventually led us to start a new platform. During the following years, we decided that this new platform would be both more explicitly socio-politically motivated and international in scope from the beginning. We aimed to take many of the experiences and lessons we have learned from running Temporary for almost ten years and try to work in experimental content and forms from the start.

Founded in 2020, MARCH, a journal of art & strategy features print editions alongside an active online platform commissioning essays, interviews, and experimental critical writing with a global perspective. After a set of online dispatches throughout 2020, for our first print journal we “occupied” the first issue of October to consider the ways in which revolutionary practice, theoretical inquiry and artist innovation may be joined in a manner exemplary and unique.

MARCH 01 (cover), October 2020. Edited by Sarrita Hunn and James McAnally, contributors additionally include Taylor Renee Aldridge, Imani Jacqueline Brown, Paloma Checa-Gismero, Tom Clark and Susannah Haslam (adpe), Nora Khan, Warren Neidich, Parsa Sanjana Sajid, Zoé Samudzi, Patrick Scorese, and Andrea Steves.

Mela Dávila Freire – What does “independent” mean for you?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – Increasingly, I [James] have strayed away from the language of the independent space, curator, and so on. I have instead started describing myself as a dependent curator, emphasizing those interconnections that are essential to any work. No project is independent and even though that language formed as an attempt to assert an outside to dominant institutions and models, it feels more and more entrapped in their logics. For MARCH, we intentionally consider our collectivity – the ways in which we are all always multiple. In that, we are connected with numerous other publishers and publications, writers, and institutions both within the various parts of our “collective research group” and through other formal and informal collaborations.

Whether we start to think more about “dependent publications” or some other term, we are especially interested in what it means to take a position – to deny neutrality, or objectivity – and to form community around those positions. The connection of dependence and collectivity, and autonomy as a way to choose communal logics rather than a sense of solitary practice feel like more liberating expressions to start from.

Mela Dávila Freire – You have underlined the importance of artists’ publications and artists’ publishing as references which inspire much of your work. Besides this, did you have any other model or reference that inspired you or influenced the way in which you conceived Temporary Art Review and MARCH?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – Artists’ publications, particularly from the 1960s to the present, offer a conceptual precedent for our work, as they expanded the idea of the publication as a site of exhibition, exchange, criticism and subjective, self-historicizing commentary, with radical potential for flattened distribution, circulation of ideas, and insertion of isolated narratives into a broader cultural sphere. Beyond historical models of artists’ publications, we really look at the present conditions of publishing and the forms of instituting in a self-critical sense. More than any external models, we have focused our attention on how to sustain an ethical and impactful publication that is global in scope. In many ways, there are not existing models for that (or at least none that fully map onto our work), so the impetus for us is to attempt to build one. We ask, What is an urgent, ethical, sustainable form for publishing in the present?” and attempt to see that live in its many modes.

This is conversant with larger concepts of institutional critique’s urgent next phase being to actually form prefigurative institutions. We publish on this idea often as applied to museums, art spaces, biennials, informal or independent spaces, and so on, but also as it applies it to our own form and operations on a daily level. Attention to how money is sourced and distributed, how power is held and shared, whose viewpoints are privileged and made public, and so on: this is enough to go to start to arrive at a “model.” How collectives and cooperatives in and out of the arts operate; how protests form and sustain, and how they coalesce into organizations at times; how mutual aid networks are documented and distributed in print and online. The models are multiple and continuously incorporated for us.

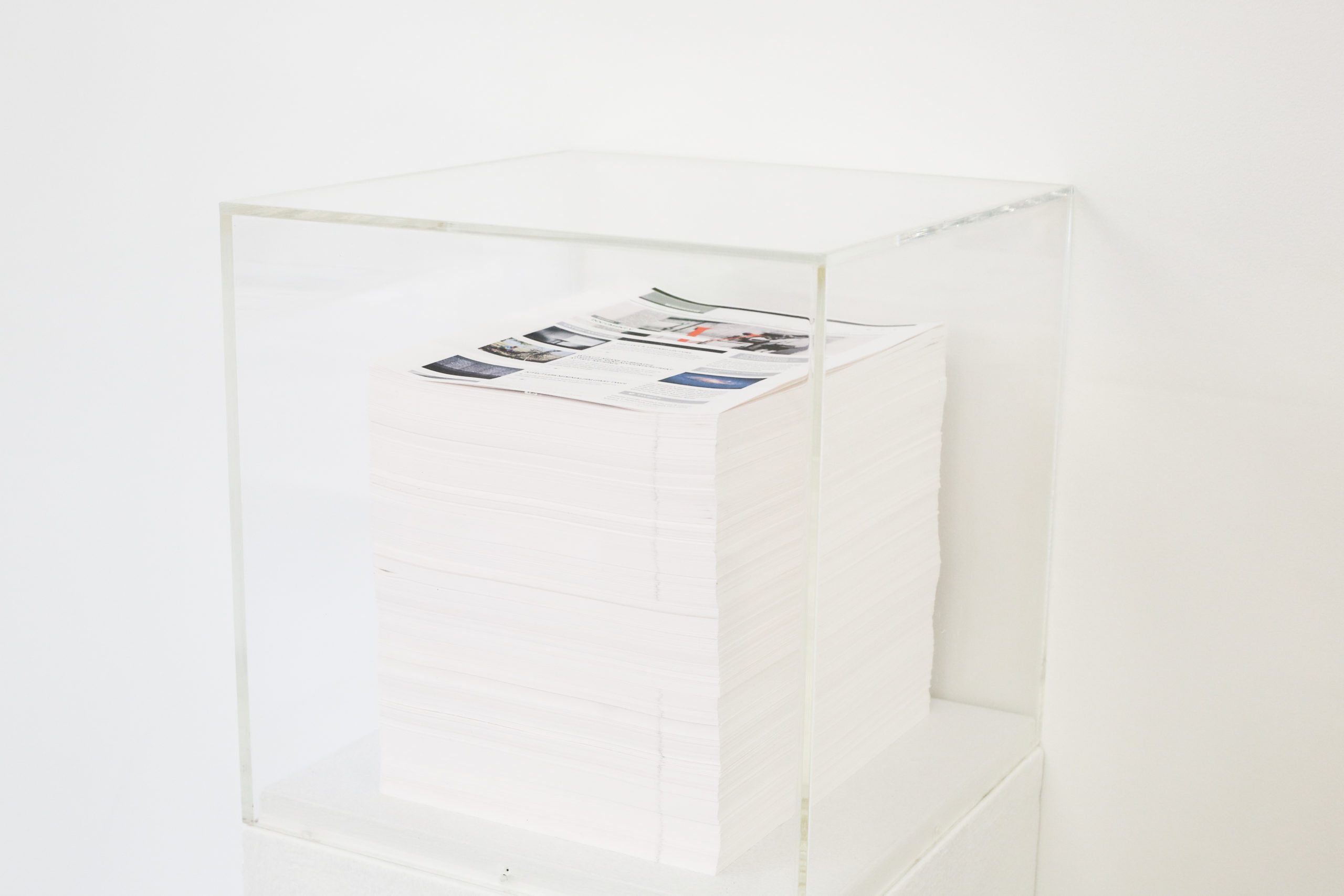

Temporary Art Review’s first five years of online publishing printed out and presented as part of our Document V anthology exhibition at The Luminary.

Mela Dávila Freire – At the time you started, how did you imagine that the project would be financially sustainable, and to what extent did this work out as expected or evolved in a different way?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – For the first three years, Temporary Art Review was an entirely volunteer project. In 2014, Temporary Art Review relaunched with an experimental “anti-profit” economic model for online publishing, driven by a bartering system which uses ad credit as a common currency to distribute value cooperatively amongst its many active contributors and partners. With this model, the momentum of the site was not relegated to a few funders, or sold to the highest bidder, but circulated amongst its authors, blurring the line between reader and writer, contributor and supporter. Shortly after this, Temporary was able to secure a small amount of annual funding via The Luminary (who was Temporary’s non-profit organization umbrella) to pay writer fees and some content management, but we were never paid as editors. We also added to the writer’s fund through selling a small number of online ads and continued to offer our writers the option to get compensated through direct payment or in exchange for ad credit. With MARCH, we felt that making sure everyone involved in the project (writers, editors, designers, etc.) should all get some payment for their work and the project should keep pace/scale with the financial support it was able to offer.

Mela Dávila Freire – Do you notice a difference in the way institutional financing works, in relation to one decade ago? Others have pointed out a dramatical regression of financial support since the crisis of 2008, accelerating due to the covid-19 health crisis, as well as the multiplication of the bureaucratic processes, and the increasing evaluation of results according only to mathematically quantifiable indicators. Is this also your experience?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – Our experience, from the founding of Temporary Art Review in 2011 to the present, has always been that publishing exists in an “unfinanced” context unless explicitly integrated with current market conditions or connected with legacy funding (such with as state grants in Europe and foundation grants in the United States). Forming from within a freefall of the publishing industry more broadly has meant that our assumptions around financial support have always been to scale with what is at hand. In that sense, we haven’t experienced decreased financial support, but operate in relation to this structural disinvestment in general and within arts publishing more acutely.

Critical writing and publishing, and the essential contexts and communities they create, are persistently underfunded in relation to other primary spheres of production, presentation and circulation of contemporary art. Art publishing almost exclusively exists using commercial models that have historically ignored those already not capitalized in some fashion, leading to a deepening of these disconnects. In the United States, there has been an incremental increase in funding for individual writers over the last decade, although still only nominal overall, and a continuing absence of structural support for publications and critical writing platforms. This only exacerbates freelancing in the field and atomization of how writing is supported and shared. As state support elsewhere follows similar trends, it seems like the publishing industry as a whole will continue to be individualized through platforms like Substack and Patreon, in which everyone is funding their own thinking.

Mela Dávila Freire – Which method for financial support is the one that you find yourselves most comfortable with, or the one you would prefer over other forms of funding?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – To date, we remain unincorporated with fiscal sponsors in both the United States (through our publisher The Luminary) and in Germany (in partnership with Liebe Chaos Verein e.V.). This allows us to pursue complementary funding across two very distinct structures. With MARCH, we are strongly supported by memberships, subscriptions, and sales of our print publication, alongside grants. We have found that a mixed model that is less contingent on one specific form of support allows us to be the most nimble, but also avoid any one model’s biases or problems. If we were wholly dependent on a commercial ad-based model, or state or foundation funding, for example, we think that would affect our content over time. We hope in the future that memberships and subscriptions can occupy a larger share of our funding in part because it builds a community around what we are doing and demonstrates attention and intention to what we publish and how it is supported, read, and received.

Mela Dávila Freire – And finally: seen from a distance, one of the reasons for your sustainability over a long period of time is the stability of your “team”. Have you ever made plans regarding the possibility of new people entering the core team?

Sarrita Hunn – James McAnally – We are both natural collaborators and platform-thinkers: there is a reason for our ongoing interest in institution-building and instituent practices! We have very complementary approaches to the work and this unique collaboration that has remained remarkably stable over a decade. This shared purpose has grounded us quite a lot over the years. With MARCH, we are intentionally inviting many more people in through advisory and editorial roles, and just recently added a long-term collaborator and co-thinker, Gelare Khoshgozaran, as a new editor.

After the recent first edition of our print journal we edited together, each following edition will feature a new guest editor. The next issue of MARCH will be edited by Imani Jacqueline Brown, an artist, activist, and researcher from New Orleans, and currently based in London. Building from her MARCH 01 contribution, “Black Ecologies: an opening, an offering,” this second edition will be a defining document toward the concept of Black Ecologies as a “resistance to extractive ecologies across the colonial-capitalist world.” Additionally, we have partnered with Dark Matter University to co-publish a series of online articles circulating around the issue to be released this fall and this issue will be designed in collaboration with Untitled (a curatorial and design team) based in Morocco. We will also be publishing numerous other print and digital projects in the coming years with a global cohort of collaborators that will continue expanding who and what MARCH is. Again, this accumulation is the publication: a set of collective research oriented towards an altered art world.

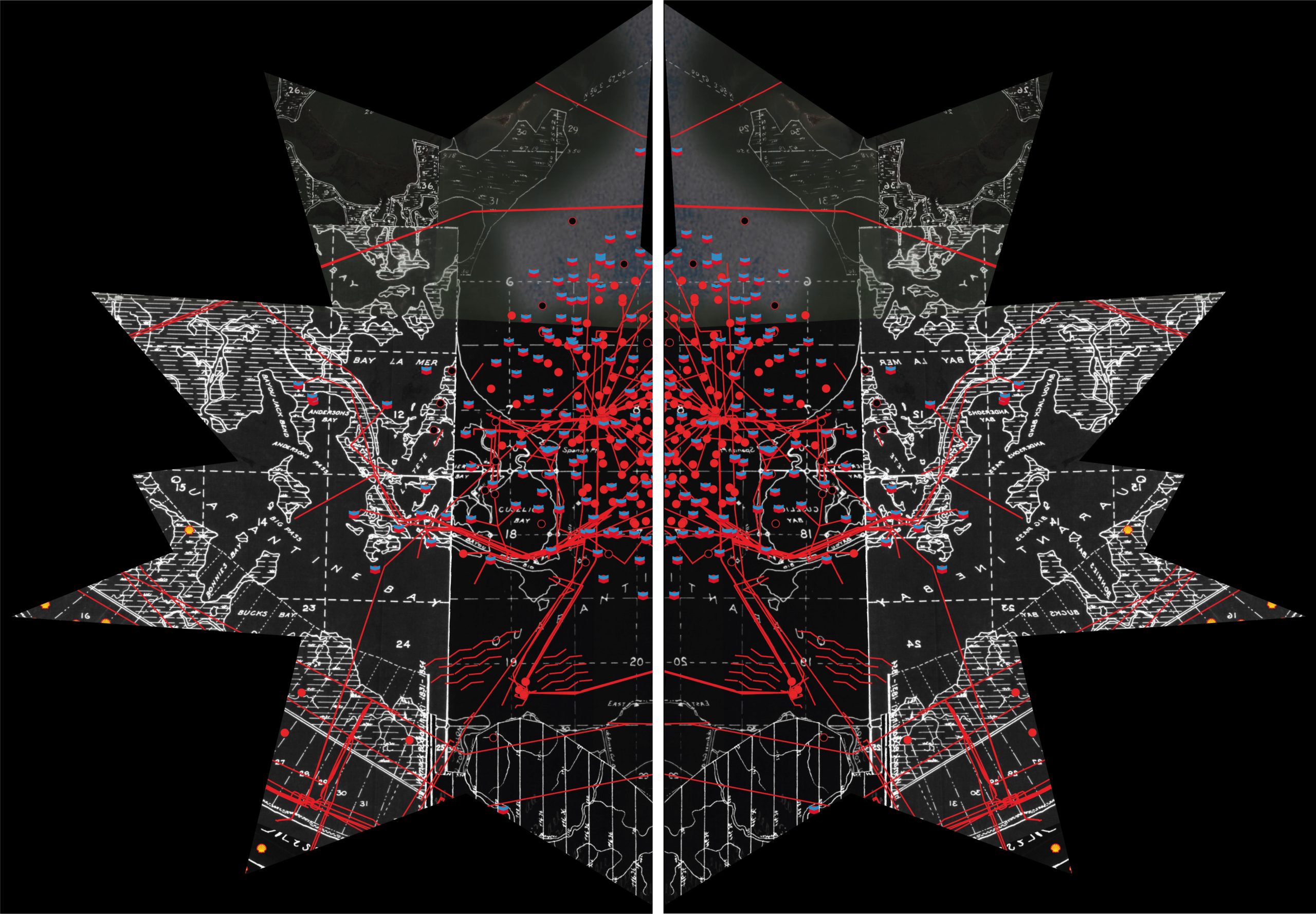

Imani Jacqueline Brown, Old Gods, 2021. Framed and reflected chart of permits for coastal development, including oil and gas wells, pipelines, and access canals in Quarantine Bay, Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana (1920-2020), mapped against antebellum Public Land Survey System (PLSS) charts (1820s-1860s). The PLSS was the first US system to plat, or divide, territory into parcels of private property.

(Featured image: Temporary Art Review’s anthology publication, To Make a Public, published by INCA Press.)

Mela Dávila Freire. Recently, a poster announced her lecture at an art school with this title: “Mela Dávila is not a graphic designer, she is not an editor, and she is not an artist, either.” Combining periods in which she has worked in art institutions with other when she worked as a freelancer, Mela traces a path that at first involved translating, coordinating and editing, then later focused on archives, and recently encompasses research, writing, and curating. Although she still has not found a name for her profession, she increasingly likes the lack of a straight line in her career.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)