Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

La condición narrativa (The narrative condition) is the suggestive title that the curator Alexandra Laudo (founder and director of the platform Heroínas de la Cultura (Cultural heroines) –an equally great title -) has bestowed on the exhibition that she is presenting in La Capella and that was the winning project in the curator’s category of BCNProducció’12.

Thinking about “La condición narrativa” triggers a whole series of references and notions that are hard to avoid mentioning here. It recalls, and Alexandra herself mentions it, Roland Barthes, who defined it as something intrinsic to the human being, given that we communicate our experience of the world through language. But she also refers to The discourse of history (or Information sur les sciences sociales, in the original version) in which Barthes proposes to deconstruct the traditional types of discourse, underlining the blurring of the frontiers between the fictional and the historical story, to restore to the latter its basically narrative condition.

The narrative condition is also reminiscent of certain narrative models, particularly those stemming from film, characterised by their zeal for liberty, as can be seen in the cases of Chris Marker and Jean-Luc Godard.

Let’s also not forget The Otolith Group, made up of the anthropologist Anjalika Sagar and the author Kodwo Eshum, whose projects aimed to create a perception of facts through texts and images related to the media of communication… Marker and Godard also went there…

And finally let us think of Francis Alÿs, whose proposals can be revisited not just through videos, photographs, drawings or publications but also through stories: a man travels through the streets of Mexico City pushing a block of ice until it completely melts away; in Peru, 500 volunteers manage to move a sand dune a few centimetres using just shovels; a man walks through the streets of Mexico, with a pistol in his hand, until he is finally intercepted by the police…

No doubt all of these references (and others) won’t seem so far fetched to Alexandra Laudo. Her aim is to analyse in what way, in our current world, saturated with images and completely mediated, this narrative condition, intrinsic to the human being, is becoming increasingly visual. Through this modified relationship between text and image, Laudo aims to analyse the mechanisms used in its construction, how it is placed in circulation and how it is consumed. And she does so with the help of eight artists, who exhibit their works in la Capella, but who also (and it couldn´t be any other way) include a series of parallel actions that have to do with the circulation/infiltration of these images in other quite separate circuits (postcards, emails and advertising spaces in printed and online media). .

The eight artists participating in La condición narrativa have in common the use of a language that like their references is hybrid, moving between the visual arts, film, literature and performance. They also share being part of the same generation, born between the end of the seventies and beginning of the eighties, growing up in Argentina, Belgium, Norway, United States or Spain, for whom the television and the computer have from early on formed an integral part of their surroundings.

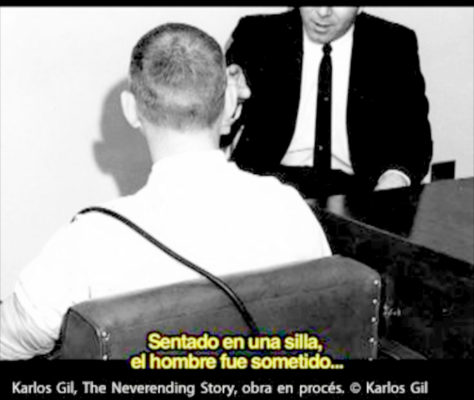

The exploration of the relations between eras, distances and languages is the axis of the investigation by Pedro Torres, who on this occasion proposes a visual and acoustic journey through space and time, through artistic, architectural, scientific and personal references. Julia Mariscal alludes to pre-cinematographic devices in an installation where the narrative focuses on the peculiar universe of the artist and filmmaker, Carlos Pastor. Ryan Rivadeneyra presents a complex visual story configured of fragments and micro-narratives, the articulation of which is revealed in the course of a one off performance. Karlos Gil shows part of his film project in process, that is made up of different films each one made in a different city and with clear winks at science fiction films of the sixties (once again, Chris Marker appears). Tamara Kuselman carried out a narration (or more precisely, a video-narration, given that in this case the existing image is based on colours). The story recounts a plan of action in the event of an emergency, in which the simulacrum becomes confused with reality. The filming (and later manipulation) by Pieter Greenen of two peaks of Mount Ararat hides a complex history that evidences historical, political and biblical tales arising out of the conflicts between Turkey and Armenia throughout history. The echoes of Duchamp’s infra-mince united with the background noise of Georges Perec appear in one of the two proposals by Marla Jacarilla that takes the floor of a patio as a point of departure to become an exploration of cartography. The same artist explores narrative processes in the elaboration of the biography of an imaginary person, through references to writers and literary characters. Closing this circle of stories is Kaia Hugin who has made a false documentary in which she looks at the purportedly Eskimo origins of her great-grandmother.

The need to tell stories is not so far removed from contemporary artists, be it through investigating relations between the real and the fictional, between public and private, to stage personal feelings or to evidence social archetypes. Using voices, subtitles, the still or moving images, the influences of film and literature, or explicit references to them, are very present in all of these pieces.

Leaving aside the irregularity of the proposals, Laudo’s curatorial gamble situates the presentation in the exhibition space on the same level as the circulation of these images in other circuits, this time, without the security net of the exhibition space. The question is, will they be able to generate questions, irritation or just curiosity? Will they be capable of generating other stories? Or will they just be lost amidst the avalanche of images, emails, postcards and advertisements that daily file past our eyes?

Montse Badia has never liked standing still, so she has always thought about travelling, entering into relation with other contexts, distancing herself, to be able to think more clearly about the world. The critique of art and curating have been a way of putting into practice her conviction about the need for critical thought, for idiosyncrasies and individual stances. How, if not, can we question the standardisation to which we are being subjected?

www.montsebadia.net

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)