Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

MoMA in New York this spring talks about the history of Japan.

On the top floor of the museum it was possible to visit, until 10 February Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde, announced as the blockbuster show of the season and strategically placed, wall to wall, beside another new historicist revision of modern American abstraction. The exhibition tried to trace parallel lines within the development of the avant-garde in the West, including milestones in art and Japanese prints of the 20th century. It wanted to offer the visitor a generous panorama of how the visual arts echoed the rebirth that the Asian country experienced after the blow of Hiroshima. However, it was rather limp in two points. Firstly, it used European and North American developments as the reference with which to measure the evolution in Japanese fine arts, the changes that the country suffered, thereby fomenting an uncensored Eurocentric reading of Japanese modernity, in a manner that at these heights one doesn’t expect from an institution like MoMA. What is more, the excess number of artists, schools and disparate decades in the three rooms that it occupied didn’t even give the intention of the curators a chance. There were pieces by creators as different from each other, as the group Ongaku, the illustrator Awazu Kiyoshi and the architect Isozaki Arata. It didn’t manage to transmit how, after the Second World War Tokyo grew as the cultural capital of the North Pacific, until it became the centre of reference it is today. On the contrary, the works are offered to the public as Japanese versions of Western milestones, of the sort the public are already familiar with.

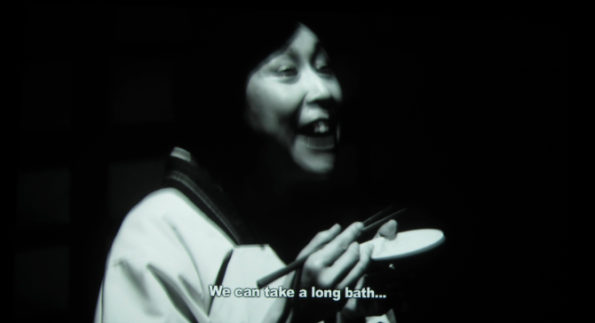

But after leaving the exhibition space, with the bitter dread that MoMA couldn’t present in a better way Japan’s transformation during the 20th century, one headed down to the second floor, to be soothed. Hidden behind the rooms of another exhibition, one finds the space that the institution has reserved for the work of Meiro Koizumi, (Gunma, Japan, 1976), the artist occupying, until the 6 May, the programme of the Project Series in the museum. In the first half of this space, in two confronted screens, one sees the videos Human Opera XXX (2007) and My Voice Would Reach You (2009). The first, filmed in his studio in Amsterdam, shows a man recounting his personal story of loss: seated, miserable, in the darkness, on a bench. The artist, with his face painted, interrupts the story each time a new person is named in the man’s tragedy. The second work, made in Japan, presents a man broken by the loss of his mother. The protagonist talks to telephone operators of customer hotlines, talking to them as if they were his mother, giving rise to dislocated conversations in which neither party can put the phone down. With this work the artist tenses the trait of Japanese cordiality by confronting it with the drama of the solitude of the urbanite. Lastly, crossing the door at the end of this room, one enters into the video installation Defect in Vision (2011), a work about blindness and history. A middle-aged couple discuss the war. The husband, a kamikaze pilot, abandons the dining room to go to work. The wife, who doesn’t want to see what is happening, carries on talking in plural and of the future. The dialogue is repeated several times, with slight variations, with different views of the same situation. The screen hangs in the centre of the room. On the other side there is another screen where one sees the wife re-acting alone parts of the first scene. For both characters, the artist hired blind actors.

The filmmaker Yasuzo Masumura explained the sense of what is sentimental in classic Japanese film as a mixture of contention, harmony, resignation, shame, defeat and escape. He contrasted it with the classic sentimentalism typical of the Hollywood melodrama that is marked by conflicts, struggles, pleasure and the search for victory. With both approaches, the museum recounts the recent history of Japan.

Paloma Checa-Gismero is Assistant Professor at San Diego State University and Candidate to Ph.D. in Art History, Criticism and Theory at the University of California San Diego. A historian of universal and Latin American contemporary art, she studies the encounters between local aesthetics and global standards. Recent academic publications include ‘Realism in the Work of Maria Thereza Alves’, Afterall, autumn/winter 2017, and ‘Global Contemporary Art Tourism: Engaging with Cuban Authenticity Through the Bienal de La Habana’, in Tourism Planning & Development, vol. 15, 3, 2017. Since 2014 Paloma is a member of the editorial collective of FIELD journal.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)