Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Some night at the beginning of the lockdown, I dreamt that superwoman came to visit me and told me the energies of the Earth gave her superpowers to her. When I woke up, I thought about Pep Padrós, an architect and teacher in Escola d’Art i Superior de Disseny de Vic (EASD) -Higher Education College of Art and Design of Vic in English-, who took a step away from it at the end of 2019. Pep was very dear to everyone lucky enough to encounter him. I met him at one of the trips to nature the teaching staff of EASD organises every year for artistic and performing arts A levels students.

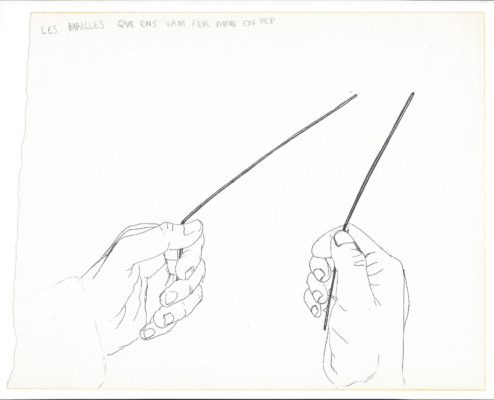

During that trip, Pep brought us around the villa l’Armentera, in the municipality of Cantonigros. Before going out to walk, we followed his instructions to put two sticks and two pieces of wire together, and bent it into an L shape. We carried one in each hand, as if they were a gun we had to hold lightly, without force. We walked restfully. In some places, the tips of the sticks got closer together. In some other places, they moved away from each other. It was magical. We got deeper into the woods and Pep drew his attention to us. When we got into a dismal spot, he made us take notice of the ivy and other climbing plants. The vegetation was dark, the ground was wet. It was the kind of place where we could find cats and snakes. He told us that the flows passing below there are the ones us humans have identified as negatives and that, in popular culture they match with all the imaginary related to evil: witches, darkness, danger. On the contrary, brighter spots is where we would find dogs and other animals considered harmless for humans. Those are the places where energies we consider positive go through: everything that does us good. In fact, aren’t we always told that if we are going to camp in the woods, the safest place to do so is where there is a dog?

Pep also made us take notice of rather less obvious stuff, like the ways in which the vegetation emerges from earth. We stopped in front of a small esplanade and we saw there was some type of herb that had grown in a circle shape. He told us that was due to the energy flows going through below. When we walked on it, the sticks on our hands moved in synchrony with the circular shape of the vegetation. Someone asked him about the energy flows going through below our towns and villages. Pep said that we can modify the circulation of these underground flows through our actions, and that, even though in other times in history, humanity was more sensitive to these flows and built in places where positive energies were found, most western societies have forgotten all of that and started building without taking any of this into account. I imagined the undersoil of our towns and villages as big knots of threads, those we clumsily pull from every side and tighten even more.

The thing is that around a year ago, the artist Marc Badia found a box full of maps and ancient mountain climbing tools in front of a mountain equipment shop in Barcelona. In the box, between all the objects, there was the book Recull d’itineraris excursionistes (Compilation of hiking itineraries), by Octavi Artís. It’s the second edition of a small notebook that briefly describes 25 routes to walk in one day only all-around Catalonia. Marc gave it to me and we thought we had to walk through all of those narrations. We shared our proposal with Jordi Lafon and Eva Marichalar, allied artists and also hikers, and we found out that work by Artís had been published around a hundred years ago, and that the author had died in 1965.

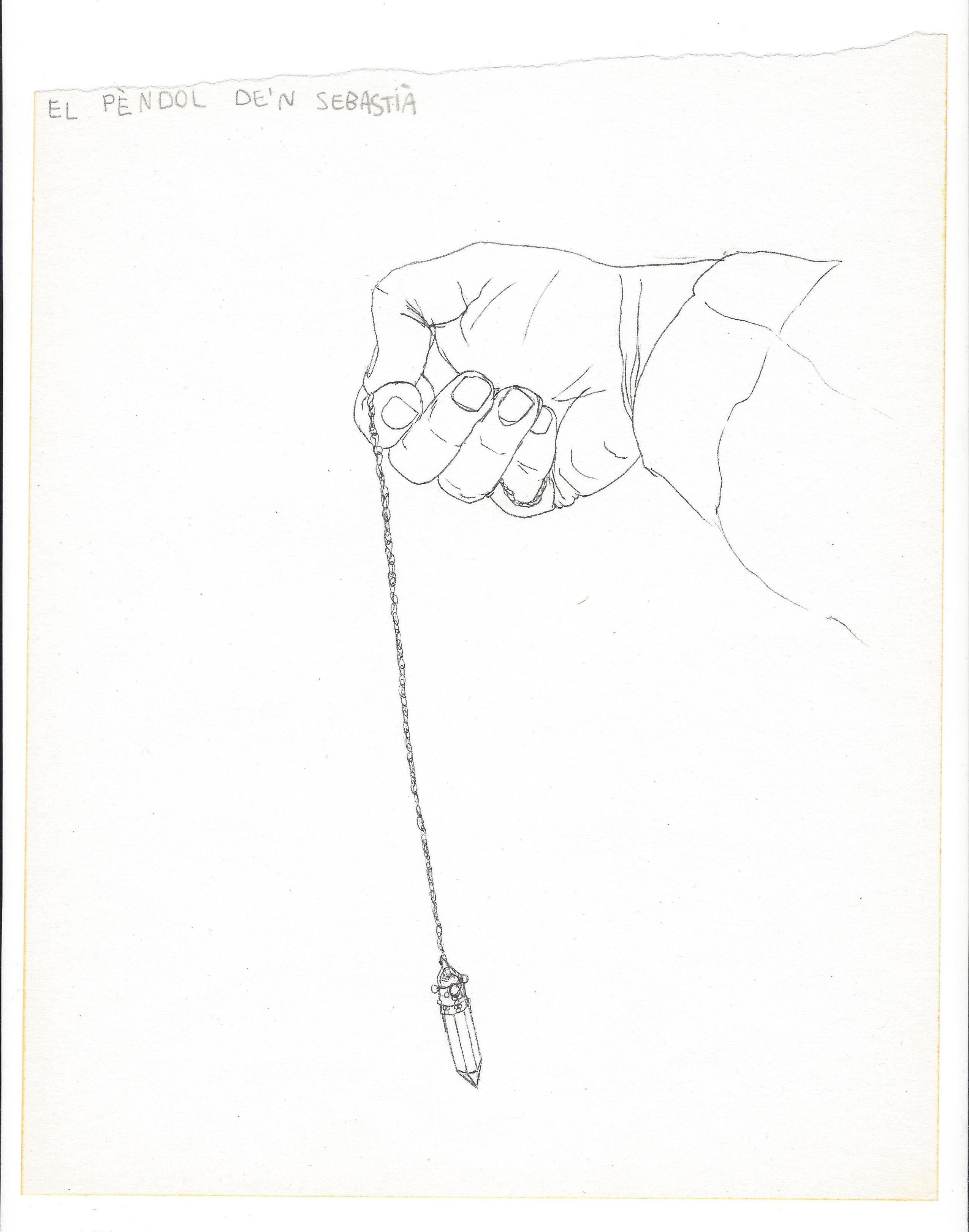

On the 3rd of August, 2019, eight of us tried to rewalk one of those routes that we would name “octavianes”, not because it was eight of us that attended that first hike, but because we wanted to give our guide some recognition. We chose the closest route to home, as the author states “from Balenyà to Taradell, Puiglagulla sanctuary, Vilalleons Castell de Saladeures and Vic”. We followed Octavi’s 400 aligned words, which, between the pages 57 and 59, describe the nearly 25 km this path takes up. Take notice that 400 words is approximately what the two first paragraphs of this text occupy. During that first octavian route it was clear to us that, with his few words, Octavi was sometimes guiding us, and sometimes misguiding us, which made us trust not only him on the routes we made afterwards. The guiding techniques we’ve developed don’t just consist in carrying a GPS and an approximate track of the route he must have followed, sometimes we also trust Sebastià Masramon’s pendulum, and sometimes it is a strange intuition expressed through imagination that we trusted. Where must have Octavi passed through? We look at the landscape and something tells us where to go. I can’t assure it always works for us -we’ve had to go back many times in each octavian route, it’s already part of our hiking- but something comforts me: the feeling that, this strange intuition isn’t too far from that primitive sensibility of feeling the underground flows Pep told us about. A young lad a hundred years ago like Octavi was even closer to that feeling that we are today, right?

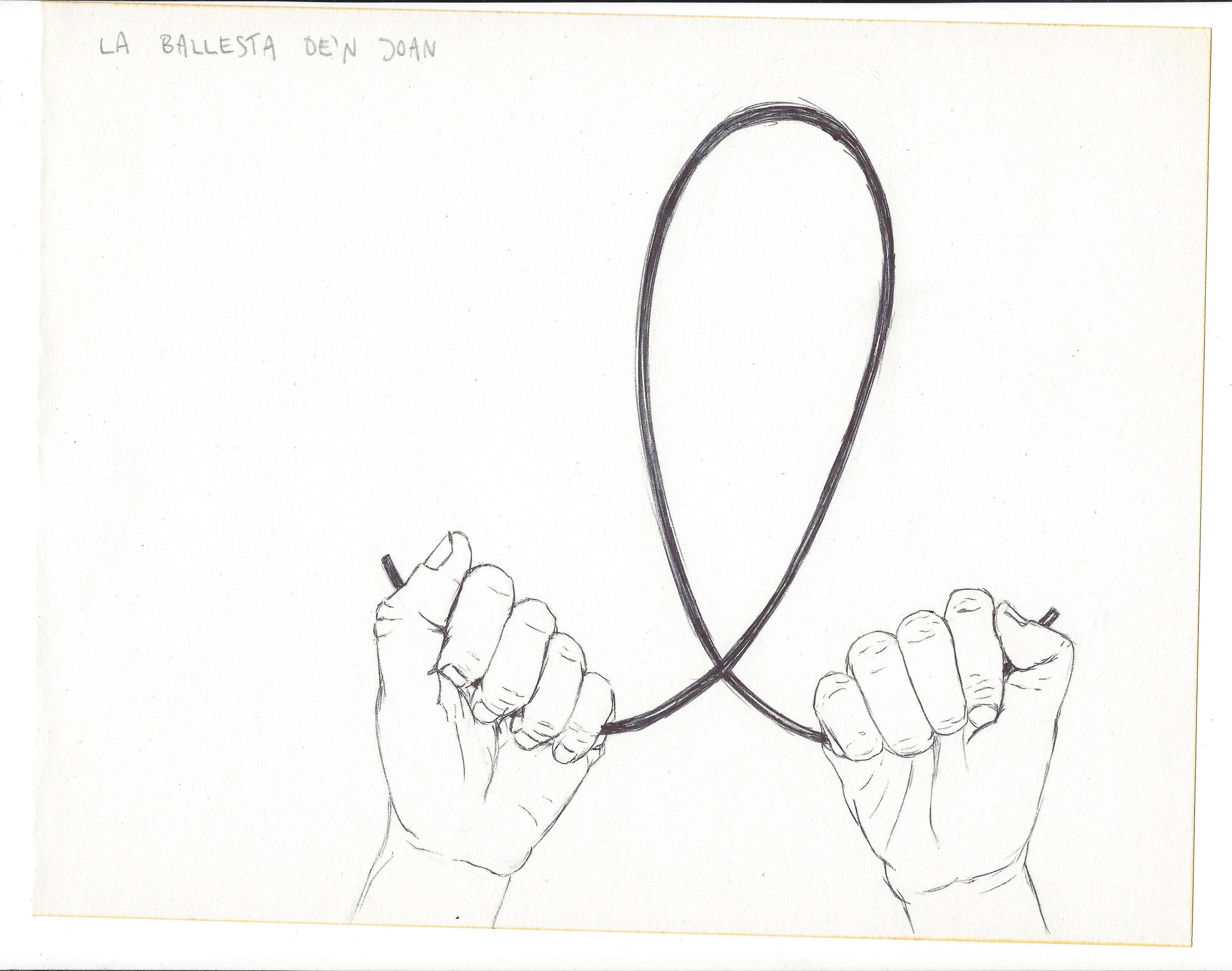

It seems quite logical to me to think those paths us humans have opened up, pass through, mostly, positive energy zones; in places the sun kisses, away from snakes and any kind of lush vegetation that would constantly eat the routes away. Away, also, from excessive dampness that would make the paths too muddy. During one of Octavi’s routes I learnt that a rhabdomancer is the person who knows how to read these underground flows. Someone who feels them and identifies them. And I recently met one, Joan Burgaya from Torrelló. He can detect the flows of underground waters, and also those of other materials, such as minerals using a pendulum sometimes or a brass crossbow in some other cases. Seeing him in action, reading a piece of land while walking on it, letting the pendulum wind at full speed, or receiving the intense blows of the crossbow, that raises up to his chest, the relationship between his body and that which flows below his feet and ours is obvious. The difference between him and the majority of us is the ability of perceiving it. Where have we left it? When did we first consider we didn’t need it?

I’m writing this text in the midst of the lockdown and the resignation to the fact that the octavian route we had planned for this March, and probably April’s too, will have to be cancelled. I think of all of those things and I think about the paths that we went through up until now, more or less frequently. Possibly for a few weeks, no human being will walk on those paths, and I imagine the vegetation, at its full spring flowering, happily spreading through the trails that we had engraved by stepping on them. Our steps were presses; our walk was the screw press. How will the paths be after all of this? Maybe it will actually be a good excuse to go deep into in them again with a fresh look, putting the memory of that primitive sensibility into practice.

Anna Dot was born on a Sunday in April. She is from Torelló and works between two worlds, worlds that she cannot perceive as being in any way separate: one of artistic production and one of reflection, writing about contexts of art.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)