Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

A few days ago Paloma Checa made an assessment of the last IKT congress celebrated in Madrid. She wrote about the subjects that had been considered in the debates, but also of what was talked about in the informal gatherings: the precarious nature of working as an independent curator or, what comes to the same thing, the precariousness of working in art. And one wouldn’t say that it was an unimaginable situation five years ago because it was also unthinkable the world would be governed by the financial markets the way it is now.

In some contexts measures are beginning to be taken: in the United Kingdom they have started the campaign “What Next”, an initiative of those responsible for cultural institutions, from theatres to museums, and also dance schools, to promote public investment in the arts. The objective is that the arts become a sort of manifesto within political life. It’s about making politicians understand the importance and value of culture (and yes, culture can generate economic and political returns) though the debate is ultimately about the type of society that we are constructing and what type of society we want to live in. In Madrid they are preparing sit-ins in the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. The aim is the same, to vindicate the value of culture

Harald Szeemann said that artists were a kind of seismograph for what happened in society, because they detected or reflected (consciously or unconsciously) the changes that were talking place. The statement still remains valid on a more global level. In the globalised world we live in, the distance is increasing, between an extremely rich class and the large number of people who are increasingly close to poverty or subsistence levels. The welfare society is winding backwards at a supersonic speed. The art world also reflects this situation: there is a world of millionaire auctions, art galleries located in the suburbs of large cities to situate them closer to private airports, collectors coming from exotic countries capable of buying everything and more, as well as endless unique works of art with prices involving many zeros. And then there are art professionals (artists, critics, curators, managers, designers, etc.) who work with ideas, contexts and content, juggling numbers and budgets. It seemed that the 19th or early 20th century idea of the artist living a life that was as bohemian as it was impoverished had been overcome, but it seems to be once again more up to date than we’d thought.

Working in art also involves experiencing another series of contradictions: we still talk of trading with unique pieces or limited editions (in totally reproducible formats); buying and selling objects; of limited access; of institutions that have grown too much so that it ends up being hard for them to adapt to the flexibility and dynamics that the times, artistic practices and public demand and of wanting/being able to be an industry. Working in art is not something “nice” or “interesting”, working in art is something necessary and by no means easy. It has to do with being critical, questioning things, a dissatisfaction, with looking for and creating meaning. Of course as an artist, critic or curator meaning can be created anywhere, on a webpage or in the corridor of your house. The problem lies in the value and need being recognised. As the writer Montserrat Roig said long time ago: “Culture in the long term is the most revolutionary political option”. It’s not by chance that it is now being targeted.

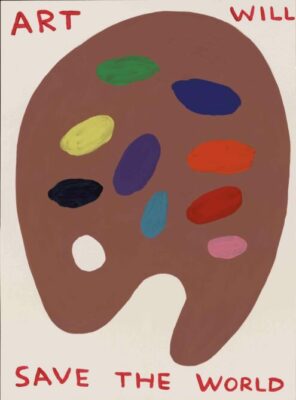

[Highligthed Image: David Shrigley. Art will save the World]

Montse Badia has never liked standing still, so she has always thought about travelling, entering into relation with other contexts, distancing herself, to be able to think more clearly about the world. The critique of art and curating have been a way of putting into practice her conviction about the need for critical thought, for idiosyncrasies and individual stances. How, if not, can we question the standardisation to which we are being subjected?

www.montsebadia.net

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)