Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Review of La caja de Pandora. Aspectos cambiantes de un símbolo mítico

Dora y Erwin Panofsky

Sans Soleil

A box. A vase. An apple. A tree. A forbidden room. A key. A forest. Pushed by curiosity, a young woman opens a box or a door that should remain closed. Another one, will stray from the right track, taking the wrong trail across the forest. Much longer ago, back in time, another one allowed herself to be persuaded by an amphibian to bite a forbidden fruit. Before her, another woman, created as a revenge by the gods, was sent to common mortals to open a box or to topple the contexts of a vase. It won’t be necessary to retell these stories’ endings because they are known by us all. We know how they will end because the punishment to curiosity, as a symptom of free will and the independence of female thought, has been infused to Western culture since the very beginning of the West’s most successful mythologies, Greco-Roman in the first place, and later, Christian mythology.

Glorified by Calderón, Voltaire, and Goethe, that exemplary intent is familiar to us all, which is why “Pandora’s box” is a familiar symbol. Pandora at the foot of Phidias’s Parthenon, being granted the gifts of all gods. Pandora being surrendered to Epimetheus. Pandora prying into that box, the same way Pre-Raphaelite painters immortalised her, obsessed with the power of her image. Pandora, created at the anvil of Hephaestus, kindled into life with the same flame that Prometheus had stolen from the gods, and had been sent by Hermes to common mortals. Pandora was the “heathen Eve” and she’s one of the rare mythological figures to preserve her vitality into this day. What other idiom is more suitable than “opening up Pandora’s box” to describe the uncertainty before the future and after the havoc caused by the pandemic and in the face of populisms and nationalisms growing rampantly throughout Europe and the world?

However, it wouldn’t have been possible to measure that symbolic might without paradigmatic studies such as this one, which contributed to spreading the reach of myth in Western art history. Originally published in 1956 by Pantheon Books, this was the first work signed by Dora and Erwin Panofsky. It wouldn’t be the last one, but the collaboration wouldn’t continue after 1956 when Dora died.

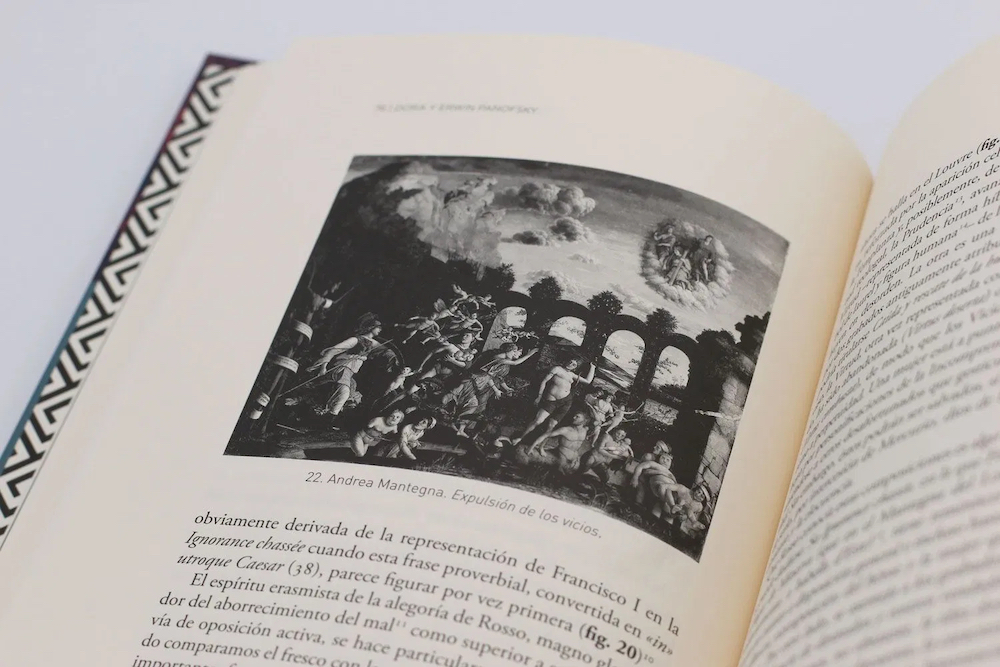

In this classical study, Dora and Erwin Panofsky outline the history of Pandora’s myth in European literature and art since Roman times to the Renaissance, keeping with the focus of interest of one of the founders of their discipline, Aby Warburg. Besides the arduous genealogic operation which covers the transmission of myth in classical literature from Hesiod, through medieval tradition, when the Church Fathers confirmed it as a predecessor of the myth of Eve and the original sin, to the rereadings by Erasmus of Rotterdam, the first author to speculate about the origins of the box or vase, glass jar. The continuity and variation of this iconographic type in painting and heraldry were also subject to incorrect ascriptions and confusion with other, similar myths, such as Psyche’s, or to the representation of Hope, the last thing left in the box when all evils were released.

Beyond the fact that, from the present, this demonstration of erudition and scholarship might be seen from the same condescending distance, from new theoretical paradigms, with which we observe this founding methodology of contemporary art history, this book is a key work in the discipline’s evolution, as well as displaying the not only material conditions of production in 1920s Hamburg. An obvious sign is that this book was treated with condescension by Erwin Panofsky, as a lesser work he wouldn’t discuss in his lectures. As pointed out in Pandora: Gender and chronology, the suitable preface by Luis Vives-Ferrándiz Sanches of the University of Valencia, “PanDora” also symbolised the contraction of the married couple’s names into one. The same name they used to sign some personal letters. Which adds a side note to bear in mind in the exhibition of erudition and thorough knowledge of the sources advanced by this study in iconology. And, also, a clue of the disregard for domestic life and care work carried through by Dora Panofsky, Mary Herz Warburg and Toni Cassirer to support their husbands’ brilliant careers. A work that wasn’t unconnected to the condition of possibility of intellectual work. Read from today’s context, rather than closing the box, this study encourages us to look beyond Hope and see what we have left.

Ana is fascinated to dive into books and movies, to approach with caution those tentacles that lie in the depths and to return to count what she has seen. She has published “Este es el momento exacto en que el tiempo empieza a correr” (Premio Antonio Colinas de Poesía Joven), the novels “La puerta del cielo” and “Hemoderivadas”, “Constelaciones familiares” (short stories, Premio Celsius Semana Negra de Gijón) and “Érase otra vez. Contemporary fairy tales” (essays). She currently lives and works between Berlin and El Paso, Texas, where she is a Bilingual MFA Fellow in Creative Writing at UTEP. Some of her texts have been translated into Portuguese, Italian, Polish, Lithuanian, German and English.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)