Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

While the multiple conversations of the assembly members are reconfiguring their own plans for the redevelopment of the marginalized neighbourhoods of the city of Asunción called “los Bañados”, where more than one hundred thousand people live, I absent myself from the meeting by mentally returning to Preciado’s text “Whom does the Greek debt heat up?” I remember that the text contrasts the hostility of the polar climate on the life of the Athenians with the imagined comfort of who would be enjoying the comfort gained by the cursed indebtedness. I remember visualizing the icy emptiness of the halls, rooms and corridors of the houses. Of the intimacy of daily life devastated by the precariousness of desire. I remember the advance of the ruin of the city that comes with the cold that arrives from the sea and the mountains. Of the city petrified by the isolation imposed by the European collapse. I remember moving forward in the story without understanding where exactly it was going because I misunderstood the meaning of the correct title reading, instead, “Who” is heated up by the Greek debt? I remember to keep in mind Zizek, who understands that societies are constituted on the basis of their forms of jouissance. That is, by means of a habit that is installed to repeat some kind of exercise of power.

As the back and forth of the projections for communal reorganization flow with the simultaneous conversations, as if modelling territories, bodies and relationships in clay, I am introduced to the stories that shape the struggle of the groups from Bañada to defend the roots of their territory. Their right to the city. Today the design of a survey to be taken from the inhabitants of the Chacarita area is being discussed. The luminous image of the form projected on that wall with the video projector and the correction of the text in real time design a collective and fleeting graffiti of a very powerful representational force. A true collaborative intervention of the administrative-legal system that historically subjects and excludes them. An exclusion that, according to the person who introduces the assembly, is the state enabling a type of exclusion based on the increase in the value of land in order to favour accumulation by dispossession.

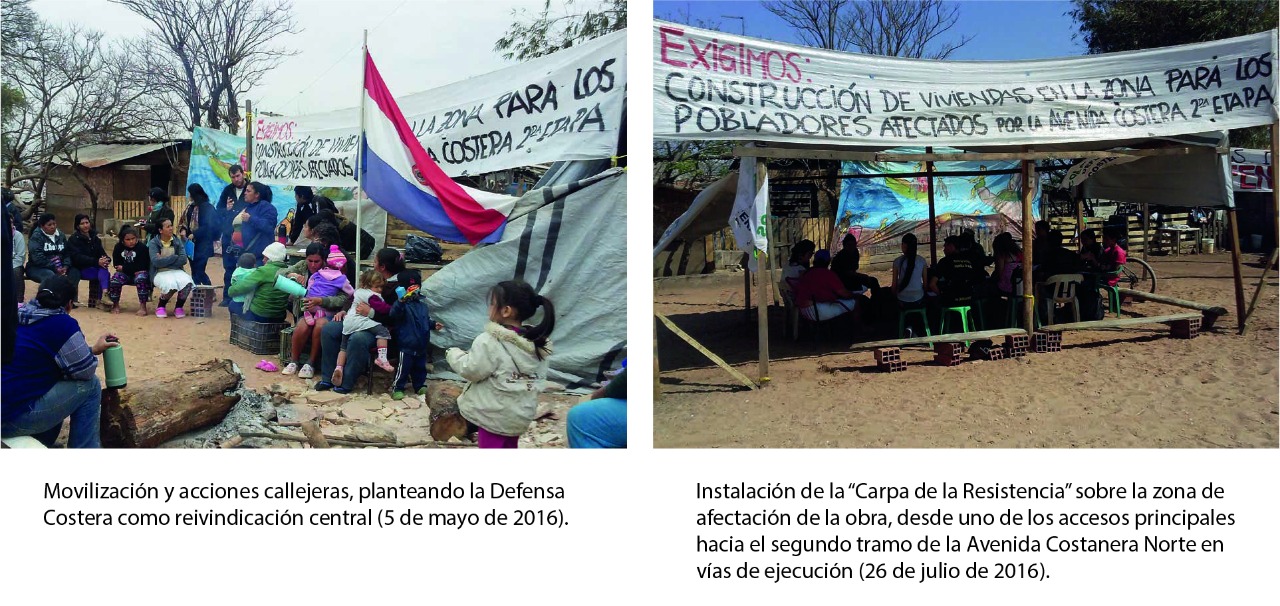

The conversations that follow are very practical, but behind them there are other scenes. Underneath each word, each category, each verbalized proposal for correction, there are life stories that I cannot fully grasp. They float in the air like formless phenomena. I try to give them a title in order to remember something of them while I apply to them a deadly and treacherous cut that, interrupting the connections with the complexity of which they participate, leaves on the other side all that I will not be able to return to. The Bañados remain as the territory of the Payaguaes Indians, and of agricultural and horticultural production in colonial times, the current history of the destruction of forests and peasant and indigenous habitats by the irruption of the agro-export model, the decomposition of rural societies and their expulsion to the urban peripheries, the expansion of the urban labour market since the seventies -especially the construction industry- which in the last decades absorbed the labour force left vacant by family agriculture, the floods and the state responses that worsened the situation by giving a glimpse of its intentions, such as the construction of the Avenida Costanera on the banks of the Paraguay River, without the channelling of the watercourses, which acted as a stopper instead of a drainage channel.

The story that captures all my attention is the one that occurs in the present time of the production of alternative knowledge to that of the State that strengthens the searches of the social groups, at the same time that it produces its own communitarian urban fabric. Public services, schools, health centres, streets, squares, clubs, cultural centres and social networks. Everything. Even the enmity and the lack of public empathy for the claim of Bañada and its coastal defence. As if their mere presence would stage an inconceivable fear, associated to “all social diseases”. An unfair relationship that turns them into an object of urban relegation. Auyero says that although its name suggests otherwise, Villa Paraíso -in Buenos Aires- is a marginalized territory. It occurs to me that something similar could happen with the Bañados.

I look at the assembly members’ faces, which reflect the heaviness of the unbearable heat. I look at their clothes, which are like mine. Wrinkled by daily use and work. I look around the room in all its dimensions. The ceiling fan that spins making metal friction noise. The yellow lighting mixes with the blue light coming from outside through the window panes and the brown curtains. Restless, I settle on the bench, creaking the old wood and rocking the two women sitting with me, as if we were in a small canoe of Mariano Roque Alonso’s artisanal fishermen. If they were, they would be two of the nine women leaders in their community. They have no name, no state recognition for their cultural contribution, and no decentralized policies in accordance with their daily reality. Abandonment that reduces their capacity to negotiate with national strategic actors and condemns them to the unsatisfaction of their basic needs and poverty.

Beyond the particularities of each abandonment, and with the version of the title you want to choose, it is very clear to me that it is about the same subject. That no one cares about the Bañados, and which sectors of society as a whole enjoy them while they are covered by a blanket of deadly water. The idea strikes me like a bolt of lightning. I superimpose the Greek scene with the Assuncena scene, making a leap of time and meanings. I reformulate my reading mistake, which is not a mistake, far from it. No one is warmed by the flooded homes of Chacarita, nor by the fact that their redevelopment, contradicting all the promises of the master plans, ends as we already know, inexorably: pushing the residents beyond their neighbourhood, where glass towers will be built overlooking the river so that the international financial sector can continue inflating its bubbles of irresponsibility. For techno-scientific capitalism to design its fantasies of banal immortality, which infantilizes us in order to continue reproducing itself. Re-expelling its inhabitants, the other migrants, those we do not count and do not see because they do not appear in the media. Those who will join the mass of segregated people who are thrown out of the nuclei of large contemporary cities that, according to Bauman, divide us into tourists and vagabonds. Another form of today’s global apartheid. That of global citizens against whom we cannot move from our tyrannizing locality, except when we are displaced so that the borders of the new castles are updated, as by the action of a digital application. Despite the assembly of multiple scenes for its concealment and justification, which seek to leave no room for any kind of appeal, regardless of the psychosocial effects of that polarized and excluding stratification.

© Images: SERPAJ (2019) El Bañado: Vida y arraigo en disputa. Territorio, desigualdades sociales y derechos humanos. Asunción

_

As if I were imprisoned by a monstrous body of water, a strong current of pessimistic emotion sweeps over me, pushing me into the sandy depths of my subjectivity. A great wave turns me into one of the tiny fishermen in Hokusai’s print, who falls out of his canoe and struggles against the onslaught of the great body of water to get back into it. Another work that, reproduced ad nauseam, shows how much one needs to feel, think and do to be able to face such proposals. From my wooden bench, next to the two fisherwomen sitting next to me, whom I honour intimately through their avatars, equally admirable for what they do here, I voluntarily count myself among those who in the Asunción area make up 9.90% of the country’s fishing population. I put on their clothes and fear that in the Bañados that great wave will also end up splashing the future skyscrapers that will be built on them. It is not necessary, in order to stop and think about what has been happening in the Bañados for decades, to wait for the cultural industries to serve as an instrument of legitimization of another of the many promising urban-real estate developments of our radiant cities, more valid than ever in the era of neoliberal intensification.

Mr. Morínigo, who is leading the assembly, makes a joke and everyone laughs at the same time as I mentally ask myself: who the fuck is heating up the Bañados? I laugh desperately, tuning in to everyone’s laughter. A little out of reflex and a little so as not to attract attention and go unnoticed. I don’t want them to imagine what I think, nor to infect them with my emotionality. I am overcome with unbearable disappointment. Morínigo thinks I’m laughing at his joke enunciated half in Spanish and half in Guaraní. Did you understand? he asks me, pointing at me with his index finger, incredulous and exultant with joy, thinking that I did. Los Bañados, the level of preparation of the assembly and the collective intelligence of the chacariteños and chacariteñas deployed in this school to defend their right to the city make me want to learn the profound creativity and strength of the Guaraní language. I feel it as a debt I owe not only to my Paraguayan-Argentinean family. So I nod my head and let myself be infected by their joy and confidence in their community capabilities. This community is the material and immaterial builder of my neighbourhood, Villa 21-24 in Buenos Aires, where we went through a similar redevelopment process, and practically the first to arrive on this riverbank. Its migrants built the architecture of my ancestry. So I believe it capable of any heroism and much more. It happened in Athens and all over Greece. It has to happen in Asunción and in Paraguay, beyond any extreme material, social and cultural deprivation. In the Bañados it has been happening for many years. From the edges of urbanity, its inhabitants are questioning – like Zizek – about which metaphor will be the most suitable to think about the city and the production of identity, says the Peace and Justice Service (SERPAJ) in its reports on the popular neighbourhoods of Asuncion. In this search, their assemblies formulate the questions and answers that our rickety democracies do not want to give and show the way with a clarity and lucidity that makes me want to cry with emotion and to live here. Their assemblies bear witness to two opposing ways of understanding the reproduction and care of life: that of the machine systems represented by state institutions and that of the “plastic-social” bodies of the relegated communities.

Asunción, October 2019

(Featured Image: © Images: SERPAJ (2019) El Bañado: Vida y arraigo en disputa. Territorio, desigualdades sociales y derechos humanos. Asunción).

___

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albiol, A. (2008) Población dedicada a la pesca en Paraguay: el caso de Mariano Roque Alonso. Revista Población y desarrollo, Year 2008, Number 38.

Auyero, J. (2001) La política de los pobres. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Manantial.

Bauman (2008) La globalización: consecuencias humanas. Buenos Aires: Fondo De Cultura Económica.

Pereira, H (2018) Urbanismo excluyente versus resistencia en el espacio popular construido en Asunción. Asunción: Quid 16, June-November, Year 2018 (pp. 91-120)

Preciado, P. B. (2019) Un apartamento en Urano. Crónicas del cruce. Barcelona: Anagrama

SERPAJ (2019) El Bañado: Vida y arraigo en disputa. Territorio, desigualdades sociales y derechos humanos. Asunción: SV Impresiones.

Zizek, S. (2002) “Formal democracy and its discontents” in Zizek (1992) Looking Awry: An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture (October Books)

WEBPAGES

Diario Página 12 (2020) Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi: Asistiremos al colapso final del orden económico global. Available at: https://www.pagina12.com.ar/287069-franco-bifo-berardi-asistiremos-al-colapso-final-del-orden-e

Radio Ñandutí (2019) Pescadores se oponen a la construcción de un complejo y exigen indemnización. Available at: http://www.nanduti.com.py/2019/09/10/pescadores-se-oponen-la-construccion-complejo-exigen-indemnizacion/

Ezequiel Filgueira Risso is specialist in Cultural Policy and Management (FLACSO Argentina and Universidad Nacional de Córdoba). Responsible for the Fundación Red ECCCO: para la Educación, la Ciencia, las Culturas comunitarias y la Cooperación; whose programme La Voz Ciudadana and its community art and culture days have been declared of cultural interest by the Legislature of Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires y the UNESCO Chair of Education for Peace and International Understanding. Mail: ezequielfr@gmail.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)