Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

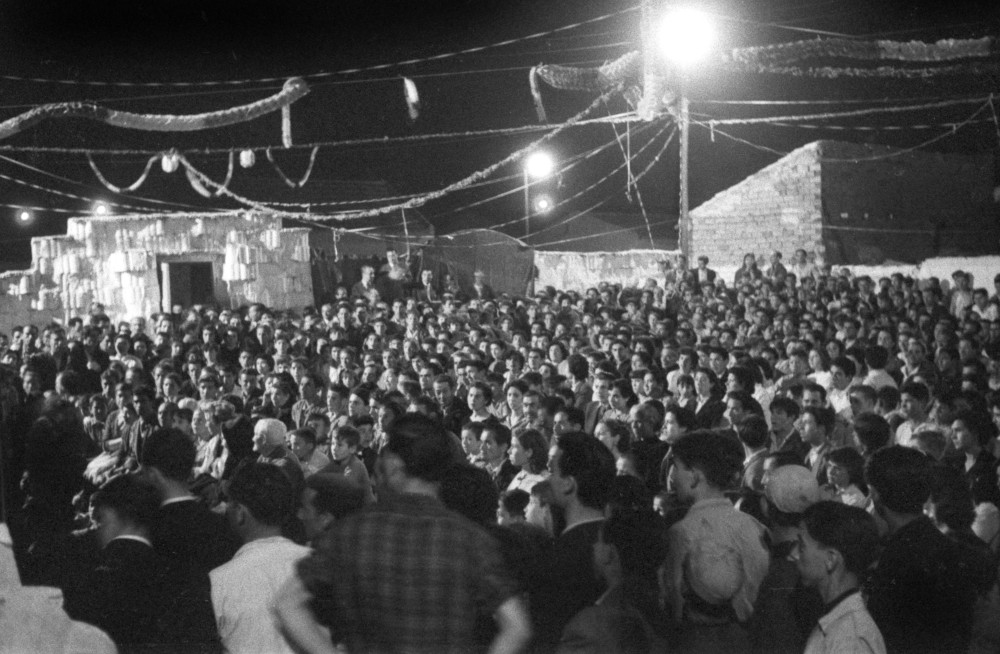

At the end of the seventies, children paint on the cobblestones of the Bairro da Sé, in Oporto; a crowd celebrates the lighting of the Pozo del Tío Raimundo in that Madrid of sacristies, barracks and autarchic misery; a woman at the back of her dew-soaked vegetable garden holds a pair of rusty garbage cans while her children run around under the shelter of an olive tree behind the Roman Gordiani. These are images that question the ways in which architecture and conflict intersect in The City in Dispute, an exhibition curated by María García Ruiz and Moisés Puente at La Virreina Centre de la Imatge in Barcelona.

Martín Santos Yubero, opening of the lighting at Pozo del Tío Raimundo, Madrid, 1957. Archivo Regional de la Comunidad de Madrid. Fondo Cristóbal Portillo

The theme is launched: sustained poverty, from the neo-realist reconstruction of post-war Italy, the avant-garde proposals of the directed settlements in Franco’s Spain, to the housing experiments that gave rise to the Carnation Revolution in Portugal. As Martín Caparrós writes, in the end it is all about the same thing: the south; that poverty here has always been hard; that in it bonds, affections, networks and social fabric have germinated; that it is, however, the misery of inequality and its effects of entrapment and violence that ends up breaking them; that undoes any attempt at shared construction.

The constellation of architectures and gestures proposed by the exhibition is enunciated from Southern Europe in an attempt to invoke the political power of ways of doing that, even in their differences, have certain common traits. Perhaps it should be specified that rather than an anthology of social housing, it is a journey of blood, sweat and tears through the tears and struggles shared between occupants and architects around the social history of housing: their associationism in the face of housing inequality, misery, institutional lack of protection and real estate speculation.

In any case, how can we speak of a Europe of social housing when the differences between its regions are always so abysmal? It is hard to imagine, but if I had to refer to that “southern Europe” referred to in the exhibition catalog, I would say that it is the same Europe, with Greece’s permission, that was hit by the 2008 economic crisis; the one where it becomes more evident -as Ignasi de Solà Morales would say- that violence is inherent to architecture. The task of García Ruiz and Puente has been to recognize the various manifestations of these social processes as a constituent part of the history of architecture in order to restore bodies forgotten by the modern paradigm and its heavy legacies through three case studies and in successive times: the quartieri of INA-Casa in Rome in the 1950s; the directed settlements of Madrid in the 1960s; and, finally, the ilhas of SAAL in Porto in the 1970s.

In this triad, architecture is always, or at least cyclically, based on a tremor, that of the agitation of communities in search of a place, a future and forms to come. Giuseppe De Santis, Carlo Lizzani, Florestano Vancini and Ettore Scola went to the Roman quartieri of the National Insurance Institute (INA) in search of those fireflies that Pier Paolo Pasolini considered lost. Pasolini himself peeked through its streets as soon as he fled Rome. The streets of the quartieri could be read as a clear reaction to the spatial homogeneity of the borgate, the proposal of Mussolini’s fascism to solve the problems of social housing to accommodate the communities -working and left-wing- expelled from the city center in the hygienist processes of sventramento (gutting) that destroyed entire neighborhoods of Rome. However, none of these quarteris surrendered to the unitary nationalism and functionalism of Italian fascism, but rather consolidated themselves as its reprobation made architecture and, with it, the fireflies appeared again in the windows of the Tuscolano (Adalberto Libera, 1954), the San Basilio (Mario Fiorentino, 1954) and the Tributino (Mario Ridolfi, 1956) buildings.

The exhibition progresses through successive beginnings: the idea of creating a city is probably one of the most exciting aspects of what is exhibited here. From the Poblados Dirigidos de Entrevías (Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza, Manuel Sierra and Jaime de Alvear, 1960) to the heterogeneous tangle of blocks, courtyard houses, pedestrian and landscaped streets of Orcasitas (Rafael Leoz and Joaquín Ruiz Hervás, 1966). There, modernity looked for different ways to be introduced in the bosom of Francoism: few examples are more representative, according to Carlos Romero Rey, to make explicit that the neighborhoods are the greatest exponent of the fact that in the face of scarcity, the best remedy is the collective practice of collaborative and consensual dignity.

Orcasitas was built on mud and fear by thousands of emigrants from La Mancha, Extremadura and Andalusia who left the peasantry in the fifties in search of work in the capital. It is a pioneering experience in the development of responsible and socially sustainable urban planning, the result of an exemplary associative movement with young architects and students willing to learn from the hand of the inhabitants themselves. The so-called Meseta de Orcasitas was made up of shantytowns and substandard housing built by its tenants, often at night to prevent construction work from being halted. In the seventies, the Orcasitas Neighborhood Association managed to involve the Ministry of Housing to initiate an expropriation operation to provide urbanization and services to the area. To this end, a partial plan was drawn up which came to be considered the first self-managed urban development experience in Spain: the neighbors, through the Asociación de Vecinos de Orcasitas, managed to get the Ministry of Housing to initiate an expropriation operation to provide urbanization and services to the area.

Given the title of the exhibition, the curators challenge us with a final question: How does architecture behave in a context where conflict has broken out; where bodies, in their discrepant agitation, have taken over the city?

In August 1974, a few months after the beginning of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, the provisional government created the SAAL (Local Ambulant Support Service), headed by architect Nuno Portas, an organization formed by technical brigades that offered support to associations of residents, conceived in the heat of the revolution and in the context of a pressing need for housing throughout the country. It was then that architecture moved to the rhythm of the revolt: it became a body, it organized itself, it acted with and for the people of the most disadvantaged popular classes. From this experience, and from the hand of Álvaro Siza, Pedro Ramalho and Sergio Fernández, the Ilhas proletárias were born, small houses supported even on a womb of ruins; built in the interiors of the houses of the small commercial bourgeoisie of Oporto.

However, the future does not exist in the future: it exists – or rather, insists – in the past, which is why this exhibition is so relevant. Here the photographs, plans, models and visuals presented do not act semiologically as an icon but as an index, a continuity between the meaning and the signifier exhibited, since the city is still in dispute and those roads that seemed to go one way are now shown back, threatening. Now more than ever it is necessary to populate that space we once invented to put somewhere our desires, our aspirations. That place has a name, it is called city and we must learn to conjugate and dispute it.

[Highlighted Image: Italo Insolera, borgata Gordiani, Roma, 1959 © Anna Maria Bozzola Insolera]

Pau Olmo Ciges (Valencia, 1996). Architect by the Polytechnic University of Valencia and Master in Advanced Architectural Design by the Graduate School of Engineering. Hokkaido University, Japan. His work was part of the Spanish Pavilion of the Mostra Internazionale di Architettura of the Biennale di Venezia, 2018 He also writes and researches on architecture, technology and contemporary art.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)