Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

1

Monday, 11 May 2020

8:15

It’s been raining non-stop for three days. This morning, when I woke up and, still in bed, looked out of the window, it seemed to me the storm had abated, and that cheered me up a bit. But when I went into the kitchen to make coffee, I saw that it hadn’t really stopped raining: the torrential downpour of the last few days had just turned into a steady silent drizzle. A dense grey curtain of mist covered the slopes of Pení. In theory Xavi was coming to pick me up at half past eight, but last week there were still police controls on the road into Cadaqués. What would he do if they stopped him? What excuse would he give them? Xavi had told me not to worry, that he had a perfect alibi, but he didn’t actually specify what it was. ‘Tomorrow I’m going to come and get you in Cadaqués and we’ll go and see the exhibition,’ he said to me on the phone, sounding confident. He had called from a phone booth, ‘just in case’. ‘One of the last few that still exist here in Sabadell. I’ve been walking around for nearly an hour’. He also told me that the exhibition was about postcards. ‘But not only about postcards,’ he added, without giving more details. When you think about it, I thought, it makes all the sense in the world. Sending a postcard is as anachronistic as calling from a phone booth. Perhaps the only way to escape the stupidity of our time is anachronism, I said to myself, before going to sleep. Perhaps being anachronistic is the most effective way of rebelling. A form of rebellion as silent and compact as the rain that envelops Pení today. Stubborn, fertile, dissident, almost invisible.

2

An anachronism is a kind of transitory insanity, a crack, an interruption of the dominant temporal narrative. The anachronist inhabits a time outside of their time, a condition that is usually greeted with scorn or parody. Take the motorway, for example. Right now, it’s an absolute anachronism. I think we should go by the back roads and avoid the tolls.

3

We’ve reached the bends without a problem. No controls and no police. Very strange sensation as we drove through Cadaqués. Not a soul, everything closed. The supermarkets weren’t open yet. The streets deserted. Today makes it a week since I was last in the town. Xavi showed up early in the morning in his pearl grey Touran. He didn’t want to get out of the car. The truth is that I had trouble recognizing him with the mask on. I asked him if he wanted to come up for coffee. Nothing doing. ‘We only have an hour to go round the exhibition, between twelve and one. We’re tight for time.’ And he was right, because it was almost nine. I settled down in the back seat next to a yellow folder full of papers. ‘What’s this’ I asked. ‘The exhibition. Have a look if you want,’ he replied, without taking off his mask. The folder had a sticker on it: ‘NOTHING NEW (working title)’. As we were coming to the end of the first series of bends, just short of Perafita, I asked if we could stop for a moment. A black cloud was hanging over the horizon. It struck me as an unrepeatable image and I wanted to take a photo of the holiday village. A postcard of desolation. For the tourists of the future.

4

It turns out that Manel, the owner of the Sis gallery in Sabadell, takes his dog for a walk every day between twelve and one. ‘Religiously,’ Xavi stressed. That was the best time to visit the gallery. What’s more, it was the only possible time. ‘Outside of that slot it would look suspicious,’ he explained, as we left one of Empuriabrava’s dreary roundabouts behind us.

5

All of a sudden he turned off in the direction of Castelló d’Empúries. ‘I think this is the wrong way,’ I said, a little anxiously. I’m not usually an insistent co-pilot. Not having a driving license makes me an utter ignoramus in automotive matters. When I’m in someone’s car my maxim is to go unnoticed, try to give the minimum of indications and, if possible, dodge all responsibility. In short: disappear. As a co-pilot I’m a zero on the left. That said, I’m a very efficient zero. A zero that always strives to be something less, to be less than zero. That isn’t a virtue that can be attributed to all zeros. There are plenty of zeros that want to stand out, that want to be more zero than the others. The very idea is absurd and, what’s worse, counterproductive, because the more zero you want to be, the more intrinsically close to zero you become, the more essentially zero you are, whatever the essence of zero may be. Being a zero, in fact, means containing everything in potentiality, which leads us to the following statement: there is no more fortunate driver than the one whose co-pilot who regards himself or herself as a zero on the left. Don’t you understand? A zero-on-the-left co-pilot can transform at any time into a great-co-pilot, or an almost-cool-co-pilot; or even, if you twist my arm, the best-co-pilot-in-history. Meanwhile I’ve already started rummaging around in Xavi’s yellow folder, and I’m less and less concerned about getting to Sabadell. What I mean is that I’m more and more interested in the contents of the folder and less in the exhibition we’re on our way to see. This feeling must be a product of the almost two months of confinement we’ve been in. I’ve grown accustomed to preferring the copy to the original, the shadow to the light, distance to contact. In short: the sketch to the work.

‘Sorry, but I feel like taking a turn around Castelló d’Empúries. It’s where my family is from.’ He seemed nostalgic. A mood I had never observed in him before.

‘That’s fine by me. I’m not in any hurry. I just mentioned it because you said earlier that we can only see the exhibition between twelve and one, and it’s almost ten o’clock … But, sure, whatever you want. I love the streets of Castelló, especially on one of the hottest days of the year. The place is so deserted it makes the ideal setting for a mystery novel. Like now. Patricia Highsmith would have loved it. It’s exactly the kind of place where Tom Ripley would live, don’t you think?’

‘Oh shit, you’re right!’ he suddenly yelled, and just as we were entering the town he did a U-turn and raced back to the road we had come from. In principle, on paper, it’s fine to be unpredictable, but when you encounter it head-on it’s not the same. In real life there is nothing more annoying and unpleasant than an unexpected change, than an unforeseen narrative twist. COVID-19 is a tragically current example. If at the start of 2020 someone had told me that in a few weeks driving on the motorway would be anachronistic, not only would I not have believed it, I would have laughed out loud and accused the speaker of being an idiot: ‘Apocalyptic! Maniac!’ That’s life, folks: unpredictable. Xavi is basically a realist artist. Much more of a realist than the realists. A graphomaniac of reality. An artist addicted to copying the narrative twists of reality. Sometimes I get the impression that his pursuit of reality is so persistent that he conjures it into being, and it ends up revealing itself like some kind of hidden treasure. Note that I’m talking not about inventing but about finding a poetic treasure trove, like the Provençal trobadors, who used to encounter reality by weaving verses and songs.

6

One of our mutual friends has a theory that Xavi is the kind of artist who doesn’t know how to produce new things but only how to engage with things that already exist. One of those artists, she says, who is interested in art. This made me think of an observation of Timothy Morton’s: ‘Art is thought from the future.’ It’s curious, because whether it comes from the past or from the future, art always seems to be a pre-existing category, an object distributed among different temporal orders.

7

I’ve persuaded Xavi to stick to minor roads, so as to avoid tolls and police checkpoints. What on earth is contemporary art turning into? It’s becoming increasingly secret, increasingly prohibited. Dodge the police to see an exhibition! And it isn’t fiction: it’s the sad reality. As real as these cows chewing the cud outside Ultramort.

8

In mystery novels and in dreams things always happen like this: suddenly. But this is neither a novel nor a dream. This is a factual account and it’s actually happening. Let’s hope there are no unforeseen events. Bob Dylan is playing on the radio. I’ve never seen Montseny so green, so full of flowers and birds. They even fly right up to the roadside. We’ve passed a couple of trucks and a van or two, but not much else. No sign of the police. ‘Lay, lady, lay, lay across my big brass bed …’ It’s 10:49. If all goes well we should arrive in Sabadell in an hour.

9

10:55

Reality always surpasses fiction.

10

Leafing through the yellow folder, a phrase came into my head: ‘from narrative turn to narrative twist to the final disaster.’

11

‘What I’m really interested in are the ontological turns,’ Xavi suddenly declares, as if he’s been reading my mind. And then, elusive and phantasmal, he adds: ‘things have legs.’

12

Essentially, the yellow folder contains two kinds of document: postcards and papers. Flimsy sheets of fine paper in shades of ochre, violet and grey. I’ve been looking over them very carefully, afraid I might tear them. Most are covered with very rudimentary sketches of flowers, leaves, and human bodies. Or, more specifically, of details of the human body: a head, a neck, a knee. And though they are simple drawings, or precisely because of their simplicity, they seem to me to be of great beauty. That form of beauty that wants not to be disturbed, that feels more comfortable at the bottom of a drawer than in a display case, that has no desire to be exhibited. A beauty that would rather go unnoticed. I’ve just remembered a phrase by Witold Gombrowicz that says something like (I quote from memory) ‘beauty is always an accidental result of some other intention’. In other words, beauty, deep down, is a misunderstanding, an obstacle that the artist, or whoever, finds along the way. The way to where? So now I’m imagining an artist who only moves for the pleasure of moving, for the pure pleasure of movement. Maybe the very fact of wanting to find beauty does away with any possibility of finding it. It’s kind of a superstitious idea, I know. Sometimes there are things that can’t be explained. If you ask me, it’s best to try never to think about beauty. Not to look for it, not even to want it. So that when it appears, if it appears (and it seems that today it has wanted to appear), it will be something luminous and truly necessary. As I was thinking about all this I had a great urge to share my reflections with Xavi. ‘They’re very pretty, these drawings,’ I said, to set the ball rolling. ‘I didn’t do them,’ was all the reply I got.

13

I’ve decided to concentrate on the documents in the folder. From now on I’ll keep my mouth shut. I’ll make myself an exemplary zero, an archetypal zero, a zero worthy of study. In view of the constant evasions of my companion, the best thing is to avoid him, to pretend he isn’t there, as if he were a taxi driver. Exactly! From now on, Xavi will be my taxi driver.

14

The postcards are something else entirely. They are arranged according to a system of classification I don’t really understand, but which no doubt responds to some kind of hierarchy. In fact, it’s thanks to the postcards that the folder seems so bulky. In reality there isn’t very much material, or not as much as I thought. The postcards have been sorted into little bundles held together with rubber bands. As I slipped the rubber band off one of the bundles I was tempted to snap the back of his neck with it, but I didn’t because he might have got a fright and crashed the car. What concentration! What determination! He’s like a sculpture, he’s so still. The taxi driver-statue. I’ve decided to concentrate on minutely inspecting the first bundle. All the postcards have views of the Costa Brava, some in colour, others in black and white. There was even one that featured a comic strip – pretty kitsch, I have to say – in the style of Mort & Phil. A hideous thing, an absolute anachronism. While I was browsing, a series of words and ideas that hadn’t occurred to me for years began to accost me. Stuff I’d completely forgotten that it ever existed. Words like transition, uncover, Pajares and Esteso, Alfredo Landa, picnic, SEAT 600, the node, our first summer holidays … People were living in a dictatorship, but they wanted to be happy. Those postcards conveyed a joie de vivre so Spanish, so calamares and paella, that I almost started to cry. The emergence of the Spanish and Catalan middle classes: one big family gathered together under the Costa Brava sun. A Martian happiness. I look out the window and see it’s still raining, but not much. We’re driving on city streets now. ‘We’re in Granollers’, Ristol says, without turning around, practically without moving. One of those rare instances of a discreet taxi driver who doesn’t ask impertinent questions or nose into other people’s affairs. The perfect taxi driver.

15

It’s 11:35. I found a handwritten note in one of the bundles of postcards. ‘Poets establish that which endures.’ Nobody now remembers that Hölderlin was neglected for almost a hundred years, that his elegies were dismissed as a sick poet’s declaration of love to the universe. Hölderlin crossed the Alps on foot. He spent the last thirty-six years of his life locked in a room in a state of ‘peaceful madness,’ having declared the inseparable union of being with Nature. For Hölderlin, all things bore the trace of God. In other words, there is nothing that does not potentially contain the possibility of a miracle. At the same time, it’s easier to believe in miracles than not. It’s a statistical fact, they say. We live in the midst of wonders. ‘Things have legs.’

16

I reckon Xavi must have written the note. But to tell the truth, I’m not very familiar with his handwriting. You have to be quite close to a person to recognise their handwriting. I’ve always been fascinated by people who study people’s handwriting. To some extent, graphologists and writers can be regarded as cousins, even first cousins. Both spend a lot of time analysing and cataloguing words,turning them this way and that. Both call for a high level of precision. A level of precision so high, at times, as to be borderline psychopathic. In fact, this obsession with postcards makes me think a bit about the way graphologists, writers and philologists work.

17

One of the bundles of postcards – just one – has a light blue post-it note with the word ‘mistakes’. It took me a while to figure out what kind of mistakes these postcards contained. I didn’t cotton on until I turned the postcards over and read the photo captions. There are two Calellas on the Catalan coast: Calella de Mar, in the Maresme, and Calella de Palafrugell, in the Baix Empordà. It seems that in the Franco years Calella de Mar was also known as Calella de la Costa. At least this is the sobriquet with which they wanted to sell the place to tourists. The existence of two Calellas was a bit of a problem for the postcard manufacturers, who occasionally confused the two and mixed up the photos of one and the other. And though they’re only a short distance apart, Calella de Palafrugell and Calella de Mar – or ‘de la Costa’ – could hardly be more different. The picture of the former is an image of a typical Costa Brava fishing village: the bell tower, the little whitewashed houses, a rocky shore with boats and coloured buoys in the foreground. Calella de Mar, on the other hand, is more like Benidorm, with its long beach of fine sand and row of apartment blocks along the seafront. In fact, the two Calellas represent antithetical models of sun, sand and sea tourism.

But the muddles are not only of this kind. The postcards display not only traces of God – that’s how Hölderlin would have seen it, at least – but also other slips which we might call philological. In some cases I’ve found the typical confusion between towns and beaches. For example, you look at a picture of L’Estartit and then when you turn the postcard over you read: ‘Beautiful panoramic view of the bay of Calella de Palafrugell’.

18

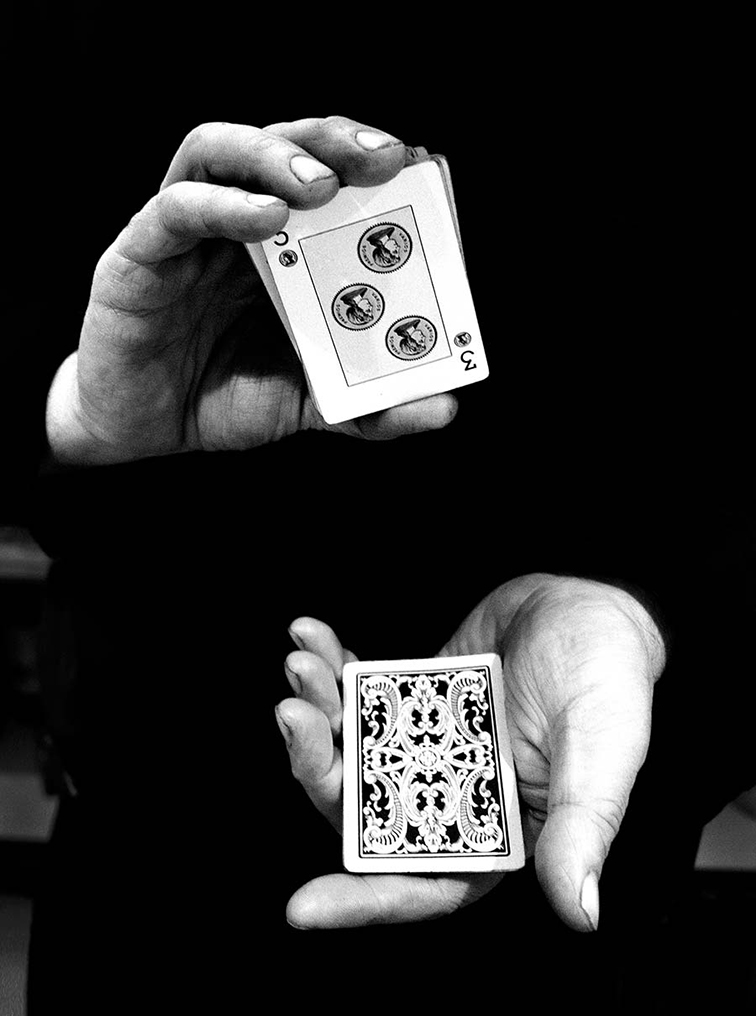

All it takes to make the errors visible is a smooth rotational movement. It strikes me as curious that such a banal gesture, the simple act of going from front to back, should give rise to so many misunderstandings. It’s like turning a steering wheel. Or it’s like a magic trick: one side of the card always gives the lie to the other.

Triumph by Dai Vernon

19

I’ve also found this paper, which I take to be the rough draught of the gallery guide. It seems there have been some last-minute changes.

Gallery guide

20

We’ve just passed Mollet del Vallès. We’re almost there. No idea, yet, of what we’ll find in the exhibition. Xavi doesn’t speak much, but every time he does, he adds more confusion to the matter. A moment ago he said (and I quote): ‘In the end we decided to open on April 15, at the height of the outbreak. It was risky, but we had no alternative. We’d been working on the thing for a long time, and we couldn’t turn back. The exhibition ends on June 12. By the way, I haven’t mentioned it, but there’s also another exhibition in the gallery at the moment: a show by Samuel Labadie, curated by David Armengol. They were supposed to open on March 16, but it was impossible. The pandemic caught them full force. ‘But weren’t we going to see your exhibition?’ I yelled, outraged. This time I had to raise my voice. I couldn’t take it anymore. The situation is becoming intolerable. There’s an air of tension in the car, at least in the back. Where Xavi is, everything seems to be in order. A philologist’s order: neat, static, celestial. The rain is getting heavier. Through the glass I glimpse a glistening grey mass. Indescribable. It must be the face of disaster.

21

‘I think I’m suffocating, Xavi.’ Silence. ‘I’d like to go out and get some fresh air, I really would.’ Even longer silence. ‘Xavi, please, can you stop?’ In desperation. ‘I’m asthmatic.’ ‘So am I. I’ve got an air purifier in the boot. We can turn it on if you want.’

22

This is much better than Ventolin! The air and my ideas have been renewed. It’s also true that the few minutes we’ve spent out of the car have been an immersion in reality. Literally: we got soaked. We have to be careful with the words we invoke. Reality is a lonely hunter, always on the prowl, likely to turn up where you least expect it and create the craziest associations.

23

You could make a portrait of a person from the contents of their car boot. Has that never crossed your mind? Yes, I know this is a diary, or a chronicle, or … a series of notes that don’t aspire to anything more than recording this peculiar trip with Xavi, but it’s always good to imagine that there’s someone there on the other side of the mirror (or the page, or the window, or the purifier: you know what I mean). Please excuse the repeated and much overworked use of the word ‘always’. It’s a tic that I can’t shake off. A manifestation of my petulance as a scribbler, always looking beyond the present, into the abyss of eternity. I have a theory about the abyss, too, but I don’t think now is the time to get into it. The abyss can always wait. Let’s leave it for lovers of the deep. I prefer surfaces. The trunk as metaphor, we were saying. There’s nothing new about that. Tarantino invented it. And before him, Alfred Hitchcock. Even our beloved Patricia Highsmith glanced at it in her novels. In any case, Xavi’s trunk reveals his passion for objects. A supremely orderly passion, of course. Another reflection of his philological drive, no doubt. I’ve made a list of all the stuff in the trunk.

2 IKEA Odger chairs (disassembled into eight pieces)

3 boxes full of postcards

1 six-pack of Carlsberg lager

1 air purifier

4 books: the Anagrama edition of the complete poems of Raymond Carver; El libro de arena, by Jorge Luis Borges; Obra completa, by Sebastià Juan Arbó; El grado zero de la escritura, by Roland Barthes.

5 packs of toilet paper

3 bottles of antiseptic hand gel

1 pack of latex gloves

2 FFP2 masks

1 box of organic oranges from L’Armentera

10 copies of the gallery guide from Samuel Labadie’s exhibition at the Sis gallery in Sabadell, with a text by David Armengol

24

Xavi’s trunk is a 21st-century cabinet of curiosities. A collection of objects that would enable us to trace a secret minimal history of our time.

25

Collecting reveals an interest in the diversity of the world and, at the same time, a fear of losing interest in the world, a terrible fear of boredom.

26

It seems to me that it’s fallen to us to live in one of the most anachronistic times in history. What do I mean by that? I’m really not sure, but I know it makes sense. A paradoxical, distant, incongruous sense, like Xavi’s collection of objects.

27

A circular age, condemned to start again, over and over, eternally. A zero age, overflowing with possibilities.

28

Purifiers are used in enclosed spaces to improve oxygen quality. In an airliner, for example, they serve to purify the air that the passengers breathe. The air is renewed in a circular cycle. On a plane you can go for hours breathing exactly the same air, over and over again.

29

A circular cycle: a zero.

30

It’s funny that both Xavi and I are asthmatic. It is as if the zero is chasing us, as if reality wants to turn everything into an absurd big zero.

31

The experts recommend that asthmatics who spend a lot of time in enclosed spaces use air purifiers. Another of the groups to which the use of purifiers is recommended are smokers. Xavi and I have been stuck in the car for almost two hours, not counting the immersion in reality. We are entering Sabadell. It’s 12:07. Eureka! Just in time.

32

David Armengol’s text for Samuel Labadie’s exhibition starts with a quote from Marcello Mastroianni, an unrepentant smoker who smoked ‘around 50 cigarettes a day for 50 years … almost one million cigarettes. It’s enough to cover the sky over Rome.’ It turns out that Samuel Labadie’s exhibition, entitled Smoke the World, includes a series of abstract drawings made with ash, small objects created from cigarette ends and other pieces produced in the artist’s studio amid tobacco smoke. Clearly, Marcello Mastroianni and Samuel Labadie, like Xavi and me, would be ideal users of an air purifier. Perhaps this whole thing is basically a strategy of Xavi’s to bring together the contrary and counterproductive passions of asthmatics and smokers.

33

I’d say that what’s happening to me is the same as what happened to those inventors of Costa Brava postcards who confused the images of one town with another, but instead of confusing towns, I confuse exhibitions.

34

The Odger chair is made of a mixture of recycled plastic – polypropylene, to be precise – and wood chips, in a ratio of 70-30, respectively, using an injection moulding process to obtain a chair in four parts. Unlike most IKEA furniture, no screws or tools are needed to assemble the Odger chair. The seat and the legs are fitted together with two pegs made of the same material as the chair, which seems to offer the possibility, in time, of producing furniture without using screws of any kind. The Odger chair is fully inscribed in the logic of the circular economy.

35

This reminds me of a story that Xavi told me the last time we saw each other, at a meal after the opening of the new Centre d’Art Contemporani in the old Fabra i Coats factory. It was just a month before the outbreak of the pandemic. A friend of his works in some kind of technology research centre and it seems that this friend and her team had succeeded in making a prototype chair from bits of plastic recovered from the bottom of the sea, among other places. These materials were very difficult to work with, on account of wear and tear and their multiple previous lives, but they did it. And then they realized they were faced with a scientific paradox: they had generated an object out of plastic, whose various degrees of recycling made it an ecological totem, but it could no longer be given a new form without breaking the cycle of reuse. They had arrived at the last ecological ceiling. ‘The only way to avoid breaking the circle’, Xavi had concluded, on that distant, almost ancestral noon, back in February, ‘is to turn the chair into an energy source.’

36

The Sis gallery is closed. Manel hasn’t turned up and Xavi doesn’t have the key. We wait in the car, in silence. It’s raining outside. It’s raining inside. The whole universe is a storm.

37

Xavi took the Ventolin out of his pocket, inhaled a couple of times, opened the car boot and started to assemble the two chairs in the rain. Then he takes out the beers and taps on the window: ‘Want one?’

38

– Now what do we do?– Close the circle.– I don’t understand.

– We have to go back to the starting point. We have to go back to Cadaqués.

– And your exhibition?

Silence. I look at Xavi through a vibrant curtain of rain.

– Did you know that Carlsberg has launched a new packaging system? It uses glue to cut down on the consumption of plastics and cardboard.

It’s true. The beer cans stick to each other, with no plastic.

– I’m hungry.

– There are oranges in the trunk.

– And cold.

– Yes, it’s starting to get cold …

– Shall we go back?

39

Exhibitions don’t disappear, they transform.

40

16:33

We’ve arrived at Cadaqués. Nothing new.

Gabriel Ventura (1988) is a poet. In previous lives he was a character in a Kafka story, a Dutch redheaded cat and a mirror in a Wyoming saloon. Poetry leads him to translate, teach, work with artists and scientists, with publishers, bookstores, galleries and museums, to research and act. In his latest book, W, the critics have seen a “fascinating labyrinth”, an “indomitable story” and “a multiformic and explosive proposal”. I thought I wanted to be a poet, but deep down I wanted to be a poem…

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)