Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

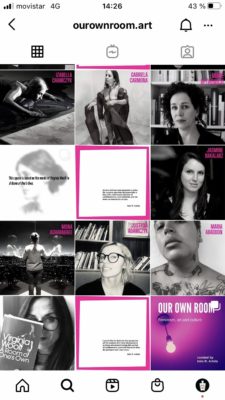

Ourownroom is a curatorial project by art historian Inés Ruíz Artola. The project began in October 2020 and is planned to end on March 8, 2021, coinciding with the celebration of International Women’s Day. A curatorial project in progress, where the twenty participating artists have been publishing their work on the social networks Facebook and Instagram; carried out under the premises determined in a continuous exchange and dialogue of conditions between the artists and the curator. In this way, Ourownroom is articulated over six months, during which each week, the account created with the same name in both networks, serves as its own room for each of the invited artists, who will deploy in that time a project carried out taking full advantage of the characteristics of the format. The idea is to end with the contributions of five writers, Florencia Abbate, Francisco Casas Silva, Belén García Abia, Margo Glantz and Kinga Stanczuk. All of them have wanted to participate by contributing from the literary field, precisely the one that gave rise to the project, thus closing the circle.

We could think that there is a paradox in the approach of this creative exercise proposed by Artola. The title, which refers to the text by the English writer Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, where she claimed for women creators the private space necessary to be able to concentrate on the feminine way of seeing and thus be able to describe the world in their own terms, appealed to a space located rather, in the Victorian context, in an interior. In any case, an intimate room hidden from the social demands and gazes to which women were, and still are, subjected. However, this own room located in the social networks, open to the avid gaze of the world’s Internet users, would seem very far from the idea that resonates in the title, if it were not for the fact that all the participating artists are performers. As historian Maite Garbayo argues, performance “is strongly rooted in the context in which it is presented, in the physical and symbolic connotations of the place where it takes place, in the incalculable intrinsic to the body of the person who appears” (Garbayo 2016, p. 58).

Therefore, what this project presents us with is precisely this appearing in the symbolic space that the social network currently represents in our culture. It adds to, and converts into everyday the strangeness of looking at others on the screen, a situation to which the pandemic of Covid19 and the consequent confinement has diverted us all. In Ourownroom, we are invited to share a space, which at times seems very physical in the face of the performative fact approached from the scrolling gaze of the Facebook or Instagram narratives, assumed with discomfort and suspicion. In this way, we share a deferred time that distances us from pure performance, whose nature is presentiality, the synchrony of actor and spectator in the ritual of the enactment of the unspeakable, of the idea (Ferrando 2009, p.11). We look at all that energy that cannot reach us, that we cannot gather with our own body to share the experience and give something back. Its communication reaches us as a suspended fact and we try to participate with some difficulty due to the distance, to the digital cut that propitiates the solitary practice of the rite. A showing from the distance, floating in the representation in front of the direct action that postulates the performance. Perhaps Facebook and Instagram accompany us in the fiction of the real event that has happened somewhere else, there where the artists performed it. How does that desire reach us?

We call Facebook and Instagram social networks and we tend to imagine them as unreal, transparent, continuous. We read them with the keys and maps of the physical space in which we move and move our bodies to relate to other people. But this transparency and the perceptual continuity of space are a fiction. The reality is that we are shaped by physical and specialized borders of space (Lefebvre). Each thing in its place and each action in its place, just as we dress for the occasion, walk and relate in spaces specific to each social relationship and we also propose ourselves in each case as a visual phenomenon, which must reckon with the legal restrictions of the platform and manage self-censorship. What regime of visuality form and employ Facebook and Instagram? As spectators and inhabitants of social networks, our gaze introduces us to these spaces deployed before our screens on the logic of an intermittent consciousness, of pluridispersed attention, of guilty availability, of procastination that, fleeing from a labor alienation, falls headlong into the more sophisticated and implacable one of compulsive looking.

In Ourownroom, bodies and spaces unfold in actions as diverse as the authors who execute them. We could articulate some categories, just to be able to enter into the artists’ own work, without the intention of enclosing them in criteria that, nevertheless, we will see overflowing in many occasions and crossing these conceptual borders without deciding their pertinent location in one more than in the others. Thus, if we talk about body, transformations, sex-gender-race deconstruction, we find actions that take place, above all, in outdoor spaces; both Agata Zbylut (Poland) and Frau Diamanda (Héctor Acuña, Peru) would be placed here with discourses, however, very distant. The second category would comprise the body, textiles and fluids, in which the place is usually the home and the studio, but not exclusively. The artists we could include in this category, Gabriela Carmona (Chile), Maria Abaddon (Peru), Valeria Ghezzi (Peru), Cristina Savage (Spain), Izabela Chamczyk (Poland), Wynnie Minerva (Peru) and Eliza Proszczuk (Poland), work on situations linked to sexuality, autobiography, social memory and the feminist point of view. In a third category defined by the body, the landscape, the environment, ecology and the archive, we find Mabe Bethônico (Brazil), Magdalena Firglag (Poland/Mexico), Liliana G. Cuellar (Mexico), Natalia Jimenez Gallardo (Spain) and Jazmin Bakalarz (Argentina), with very different approaches that would deserve an in-depth analysis that, for reasons of length, cannot be included in this review.

The performers modify with their work the space of the social network by using it as it was not intended. They propose an exchange of a different kind than what is usual on Instagram or Facebook. They ask us to stop, watch the development of an action in front of the camera, read certain handwritten notes, follow clues, images, ideas, meanings; establish comparisons and interpret. It is an experiment that brings into play a specific mode of relationship between the work and a space that we have been forced to transit in recent times. Undoubtedly, the pieces proposed here lead us to broaden our field of experience by articulating a machine of subjectivation and a narrative visuality that challenges us as spectators and witnesses; that questions our situation as subjects in front of the work from a distance to which we were no longer accustomed.

Isabel Garnelo Díez is Associate Professor at the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising of the Faculty of Communication Sciences at the University of Malaga. Her work focuses on artistic creation and research and theoretical research related to contemporary art and art theory, with a special interest in the discourses that emerged in the avant-garde and neo avant-garde periods of the twentieth century, which have continuity in the practices and theories of art in the twenty-first century. She is a member of the R&D project: Practices of subjectivity in contemporary arts. Critical reception and fictions of identity from a gender perspective (2016-2020).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)