Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

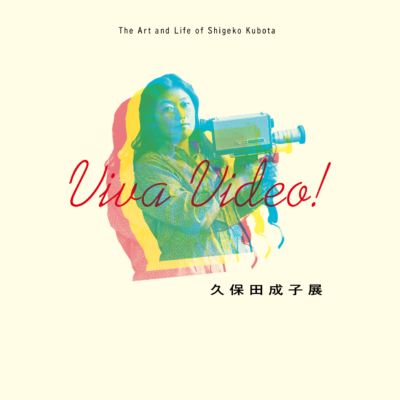

“She was always there, but very humbly, almost invisible, very much in the back. There was always Nam June Paik and George [Maciunas]. She was a mother. She was a sister and a nurse to both of them. Except when she would take her video camera, recording everything. Then she was an artist, one of the best.”[1]Mekas, Jonas, “Forward for the exhibition catalogue Shigeko Kubota: My Life with Nam June Paik,” in Viva Video! The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota, cat. exp., The Niigata Prefectural … Continue reading. With these words Jonas Mekas remembered his dear friend, Shigeko Kubota (1937-2015). Words that give a sincere sample of the humility of this artist who, despite always being in the shadows, and despite the late recognition granted in her native country, starred in some of the crucial episodes of the birth of video art. This is evidenced by Viva Video!: The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota, the first retrospective exhibition dedicated to the artist in Japan [2]The exhibition has been held at The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art (March 20, 2020 – June 6, 2021), The National Museum of Art in Osaka (June 29 – September 23, 2021) and The … Continue reading. An exhibition for which some essential passages, forgotten by the history of art, which reveal a key figure in the development of the international artistic avant-garde, have been reviewed.

Among them, and well known, the famous Perpetual Flux Fest of 1965 for which he made the famous Vagina Painting, a work for which if Kubota is somewhat known today is due, in large part, to her. But what is not so well known, and which the show brings to light, is the fact that such a performance was not her idea, but that of her partner, and future husband, Nam June Paik and her admired friend, Fluxus head, George Maciunas, who a year earlier had helped her move to New York. “I didn’t want to do it. They insisted and I couldn’t refuse.”[3] Shigeko Kubota interviewed by Tezuka Miwako, October 11, 2009: http://www.oralarthistory.org/archives/kubota_shigeko/interview_01.php (Accessed 10/02/2022). . This is how the artist recalled this episode in 2009, in an interview in which she openly acknowledges that the authorship of the piece does not belong to her. A piece that, if we look at the poster of such event, in which you can read the phrase “SEE VAGINA PAINTING!”, seems to have been used as a claim shamelessly. Since, with the exception of this one, the program only included the names of the artists and not the works they presented.

To debate here the reasons why Kubota allowed it would be too extensive, although I suspect that something has to do with a mixture between that historical Japanese feeling of gratitude for the people who help you, and that she was a young artist without possibilities, in a country where “everything was oriented to men.”[4] Kubota, Shigeko, in Greer, Judith, “Interview with Shigeko Kubota,” Op. cit. 2021, p. 174. , that thanks to her personal effort and involvement with Fluxus, she had managed to get to New York and be in that place that, professionally, seemed hopeful. Perhaps it is because of that same cultural feeling, or perhaps out of pure artistic commitment, that during those years Kubota tirelessly dedicated herself to acting as a mediator between the United States and Japan.

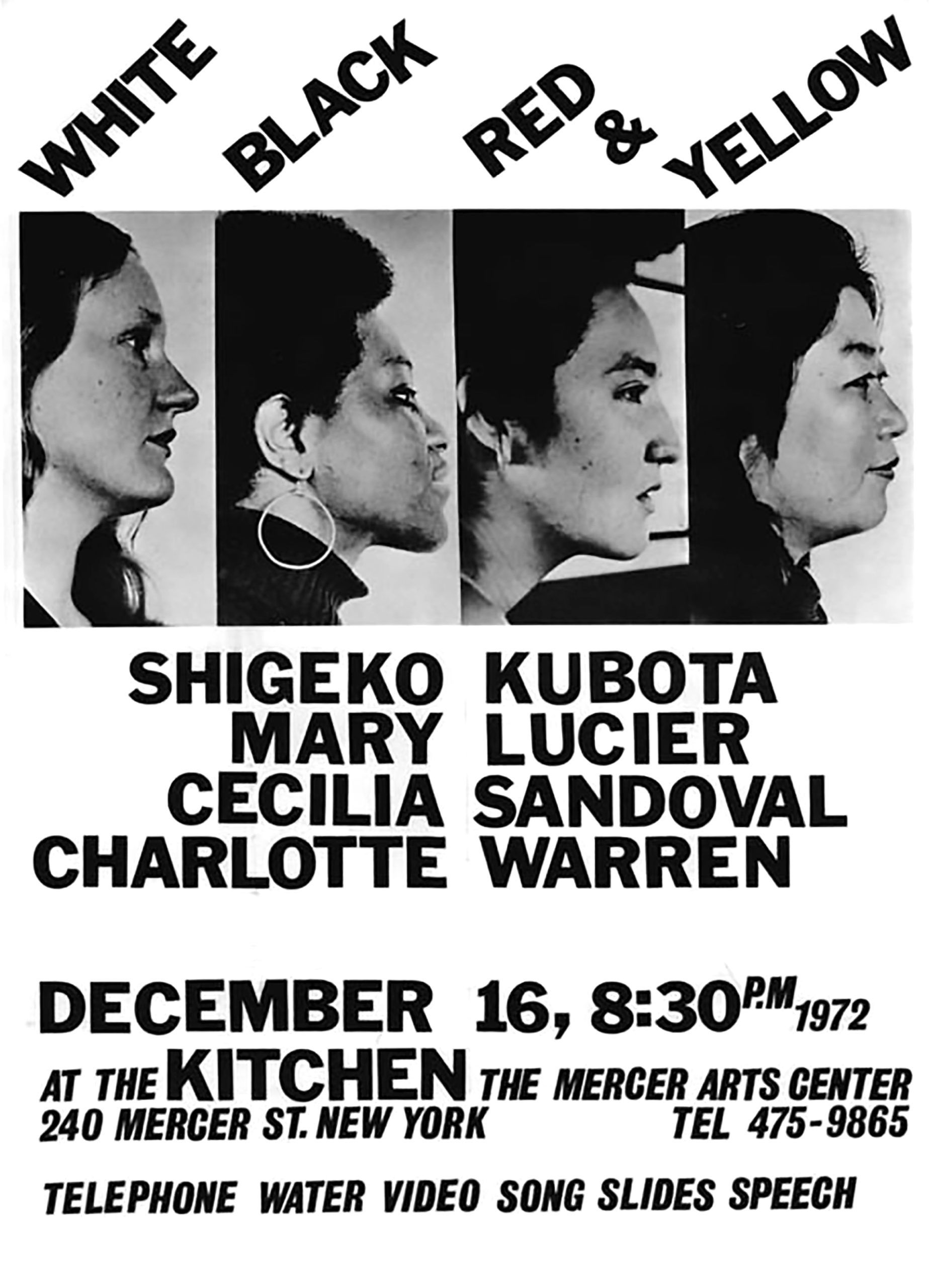

First, in 1969, she began to write about what was happening in the field of video art in New York for the Japanese magazine Bijutsu Techo. Moreover, thanks to her, the same publishing house would publish the translation, by her friend Fujiko Nakaya, of Michael Shamberg’s popular book Guerrilla Television, which had a strong influence on the young artists who, thanks to the launching of the Sony Portapak, were beginning to empower themselves in Japan. She too, like them, had obtained one of these portable video cameras through Reiko Abe [5] Wife of Shuya Abe, Nam June Paik’s collaborating engineer. On one of her trips to NY to visit her husband, she brought with her, from Japan, the Sony Portapak that Kubota had ordered. , with which she traveled around Europe recording part of the material that she would show during the Red White Yellow & Black performance-events [6]Red White Yellow & Black held two multimedia events at The Kitchen (NY), the first on December 16, 1972 and the second, and last, on April 20-21, 1973. Shigeko Kubota, for the design of the … Continue reading: the first interracial collective of women artists formed by Mary Lucier, Charlotte Warren, Cecilia Sandoval and herself, who after her collaboration with Sonic Arts Union had taken the initiative.

Poster of Red White Yellow & Black, 1972. Photo: Mary Lucier, Design: Shigeko Kubota. Image courtesy of Mary Lucier

Later, in 1974, she returned to Tokyo with her suitcase loaded with videotapes to show those new generations what was happening on the other side of the Pacific in an event, conceived by her and co-organized with Video Hiroba (the first Japanese collective of video artists), entitled Tokyo-New York Video Express. An event almost parallel to Open Circuits: An International Conference on the Future of Television, held two weeks later at MoMA, at which she presented her paper Women’s Video in the U.S and Japan [7]Queer Blue Light Gay Revolution Video, Jackie Cassen, Charlotte Moorman, Shirley Clarke, Elsa Tambellini, Yoko Ono, Fujiko Nakaya, Mako Idemitsu and Kyoko Michishita are mainly the names of the … Continue reading and about which he would publish an extensive feature for the Japanese magazine Geijutsu Kurabu:

“Men think: ‘I think, therefore I am.’ I, a woman, feel: ‘I bleed, therefore I exist.’ And recently I have bled 3,000 meters of 1/2 inch video tape every month. (…) Video is the revenge and victory of the vagina.”[8] Ibid, p. 97. , she proclaimed emphatically at the beginning of her speech.

After that, Jonas Mekas would appoint her curator of the Anthology Film Archives, where she remained for eight years in charge of programming, becoming a tenacious promoter of the work of women video artists and a true ambassador of the international video art community. For in her programming, as Bob Harris recalled, she also gave voice to guest curators presenting works coming “from Zagreb, Barcelona, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Great Britain and Canada, as well as works reflecting feminist Afro-America and Asia and Latin American and Native American sensibilities.”[9] Harris, Bob, in Hamada, Mayumi, “Video is the window of her life: the art and life of Shigeko Kubota”, Op. cit., 2021, p. 209. . It would be from there, from that transcultural and feminist space, that Shigeko Kubota supplied all the material in her hands to Barbara London, recently appointed curator of MoMA’s new video art area. It is from there, at last, that women video artists entered, victoriously, the temple of contemporary art [10] The first video sculpture to become part of MoMA’s collection, acquired in 1976 through Barbara London, was Shigeko Kubota’s Duchampiana: Nude Descending a Staircase (1976). .

(Featured image: Tom Haar, Design: Akira Sasaki. Image courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo).

| ↑1 | Mekas, Jonas, “Forward for the exhibition catalogue Shigeko Kubota: My Life with Nam June Paik,” in Viva Video! The Art and Life of Shigeko Kubota, cat. exp., The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, The National Museum of Art (Osaka) and Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2021, p. 86. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The exhibition has been held at The Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art (March 20, 2020 – June 6, 2021), The National Museum of Art in Osaka (June 29 – September 23, 2021) and The Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (November 11, 2021 – February 23, 2022). The largest solo exhibition of Shigeko Kubota’s work, with 21 pieces, up to the present show, was held in 1991, during the artist’s lifetime, by the Hara Museum Tokyo, a private institution belonging to the French Arc-en-Ciel Foundation. |

| ↑3 | Shigeko Kubota interviewed by Tezuka Miwako, October 11, 2009: http://www.oralarthistory.org/archives/kubota_shigeko/interview_01.php (Accessed 10/02/2022). |

| ↑4 | Kubota, Shigeko, in Greer, Judith, “Interview with Shigeko Kubota,” Op. cit. 2021, p. 174. |

| ↑5 | Wife of Shuya Abe, Nam June Paik’s collaborating engineer. On one of her trips to NY to visit her husband, she brought with her, from Japan, the Sony Portapak that Kubota had ordered. |

| ↑6 | Red White Yellow & Black held two multimedia events at The Kitchen (NY), the first on December 16, 1972 and the second, and last, on April 20-21, 1973. Shigeko Kubota, for the design of the poster of that first event altered the order of the colors in the name of the collective. |

| ↑7 | Queer Blue Light Gay Revolution Video, Jackie Cassen, Charlotte Moorman, Shirley Clarke, Elsa Tambellini, Yoko Ono, Fujiko Nakaya, Mako Idemitsu and Kyoko Michishita are mainly the names of the artists her paper focuses on. Noting, furthermore, “that the success of the video art movement is due in large part to the hidden devotion of women organizers,” such as Phyllis Gershuny and Beryl Korot (creators of Radical Software magazine) and, of course, Seina Vasulka and Susan Milano, who since 1972 had begun organizing the Women’s Video Festival at The Kitchen. Kubota, Shigeko, “Women’s video in U.S. and Japan,” in Douglas, David; Simmons, Allison, The New Television: A Public/Private Art, The MIT Press, Cambridge/London, 1977, p. 96-101. |

| ↑8 | Ibid, p. 97. |

| ↑9 | Harris, Bob, in Hamada, Mayumi, “Video is the window of her life: the art and life of Shigeko Kubota”, Op. cit., 2021, p. 209. |

| ↑10 | The first video sculpture to become part of MoMA’s collection, acquired in 1976 through Barbara London, was Shigeko Kubota’s Duchampiana: Nude Descending a Staircase (1976). |

Art historian, curator and independent researcher specializing in contemporary Japanese art. He is currently working on the relationship between art, corporeality and technology.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)