Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

As a hyperbolic image that offers a temporary bridge, and bridging the distances with the Guatemala of the seventies, the information presented by the Forensic Architecture (FA) collective in its exhibitions Towards an Investigative Aesthetics (2017), of the museums MACBA, Barcelona, and MUAC, Mexico City, functions as a brief artistic-cultural approach to the complex current political and social scene of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. At the same time, both the siege of the Ixil Mayans by the Guatemalan armed forces from 1978 to 1984 and the implications of three electoral processes taking place throughout 2020, which the indigenous people of Bolivia will have to face, facilitate the understanding of culture no longer as an instance of representation of reality through beautiful objects[1], but as a device for the exercise of power, not only macro-political. That is, as a reactionary instrument, which opposes innovation and difference.

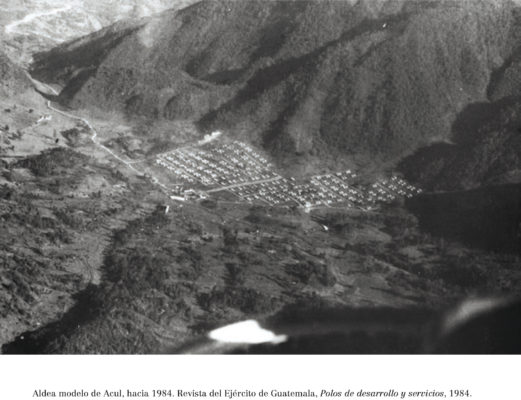

Through architectural and environmental evidence, the FA collective gives an account of the violence suffered by the Ixiles, characterized as the culmination of a secular colonization process. This process included the intensification of armed violence on their villages, catalogued in the context of the Cold War as “infiltrated communist cells” and “subversive”; the destruction of the environmental conditions on which they depended for their subsistence; and the territorial reorganization of their population based on the construction of development poles where they were re-educated in modern cultivation techniques. These procedures, which were in line with the strategic and political logic of colonization because it sought to expand the frontiers of development, ensured the conversion of autonomous people into citizens and participants in the national economy, while facilitating the transparency of an environment that was beyond the control of the US military, along with other scenarios in the Caribbean (MACBA and MUAC, p. 120:31).

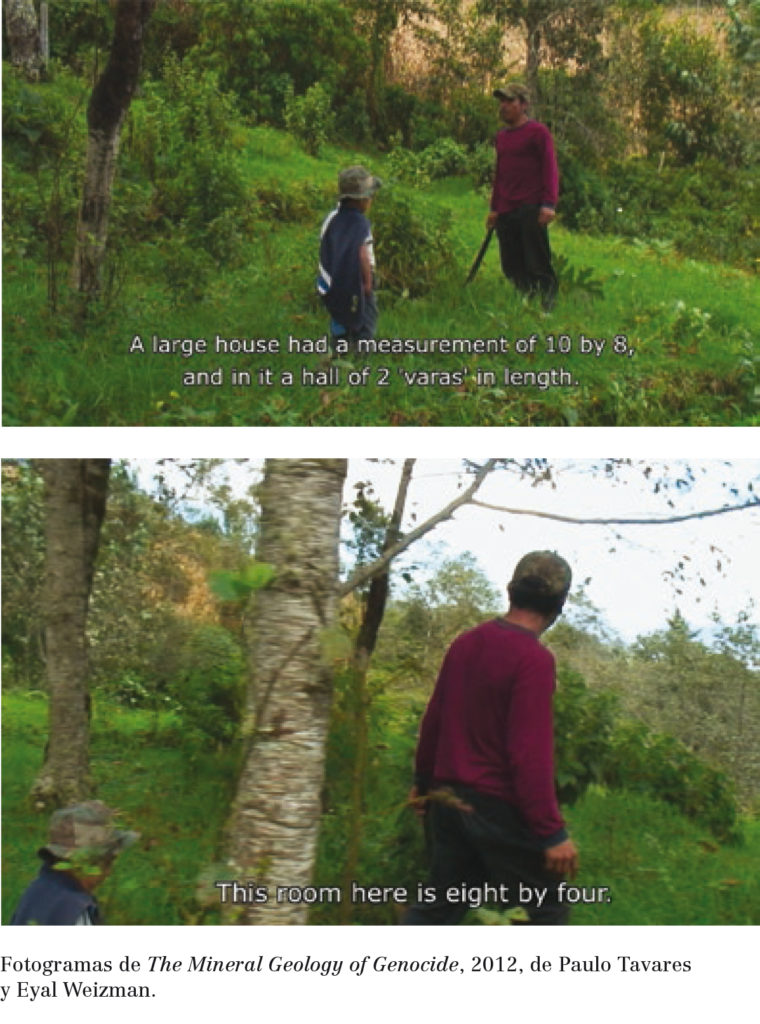

Stills from The Mineral Geology of Genocide, 2012, by Paulo Tavares and Eyal Weizman.

Stone from the foundation of a house set on fire and destroyed during the massacre of Pexla Grande, 1982. Photo: Forensic Architecture, 2011

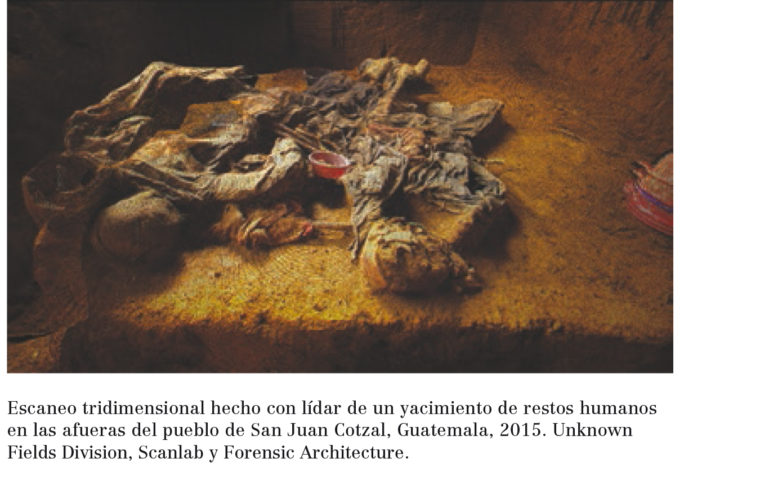

Three-dimensional lidar scan of a human remains site on the outskirts of the village San Juan Cotzal, Guatemala, 2015. Unknown Fields Division, Scanlab and Forensic Architecture.

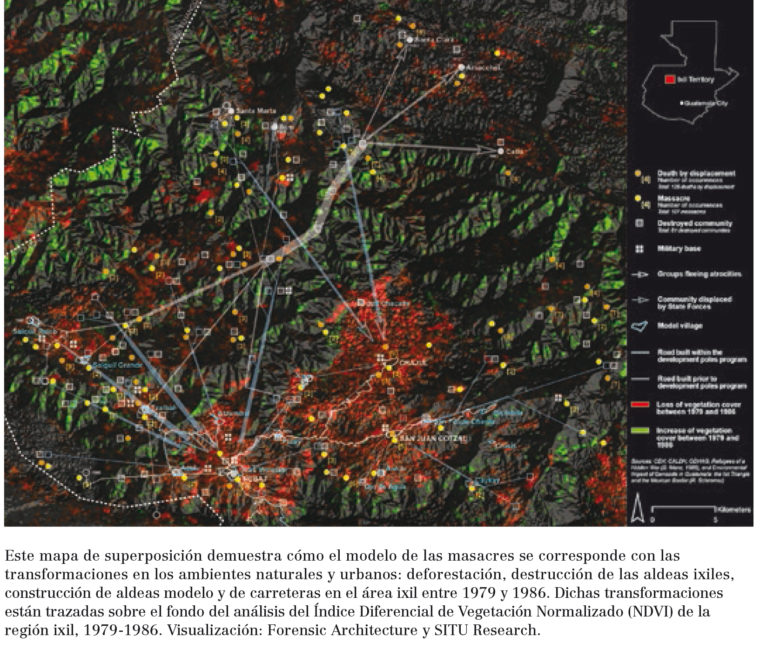

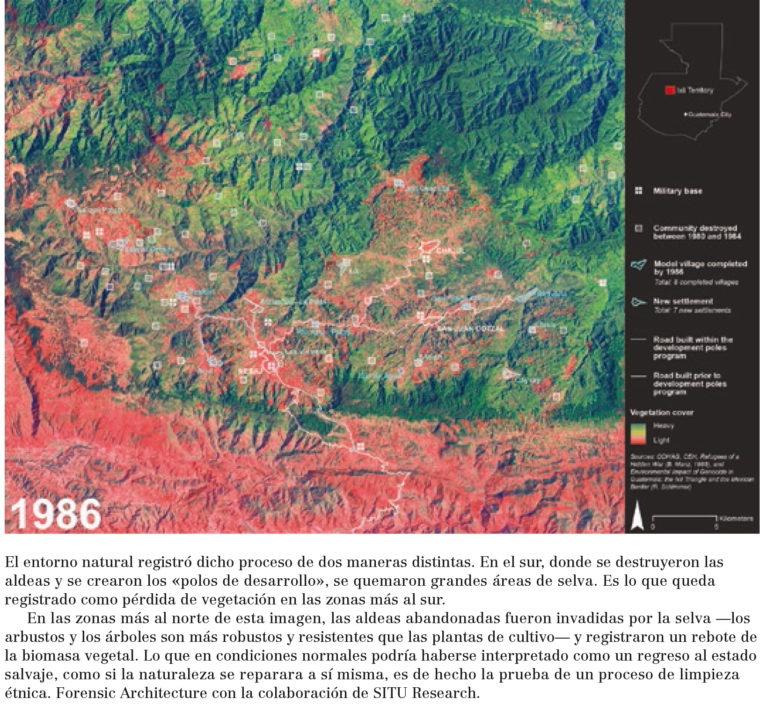

This overlayed map shows how the pattern of massacres corresponds to the transformations of natural and urban environments: deforestation, destruction of Ixil villages, construction of model villages and roads in the Ixil area between 1979 and 1986. These transformations are outlined on the basis of the analysis of the Normalized Differential Vegetation Index (NDVI) of the ixil region, 1979-1986. VIsualization: Forensic Architecture and SITU Reasearch.

The natural environment recorded this process in two different ways. In the south, where villages were destroyed and “development poles” were created, large areas of forest were burned. This is what is recorded as loss of vegetation in the southern areas.

In the northern areas of this image, the abandoned villages were invaded by the forest – the bushes and trees are more robust and resistant than the cultivated plants – and registered a resurgence of plant biomass. What under normal conditions could have been interpreted as a return to the wild, as if nature repaired itself, is in fact evidence of a process of ethnic cleansing. Forensic Architecture with the collaboration of SITU Research.

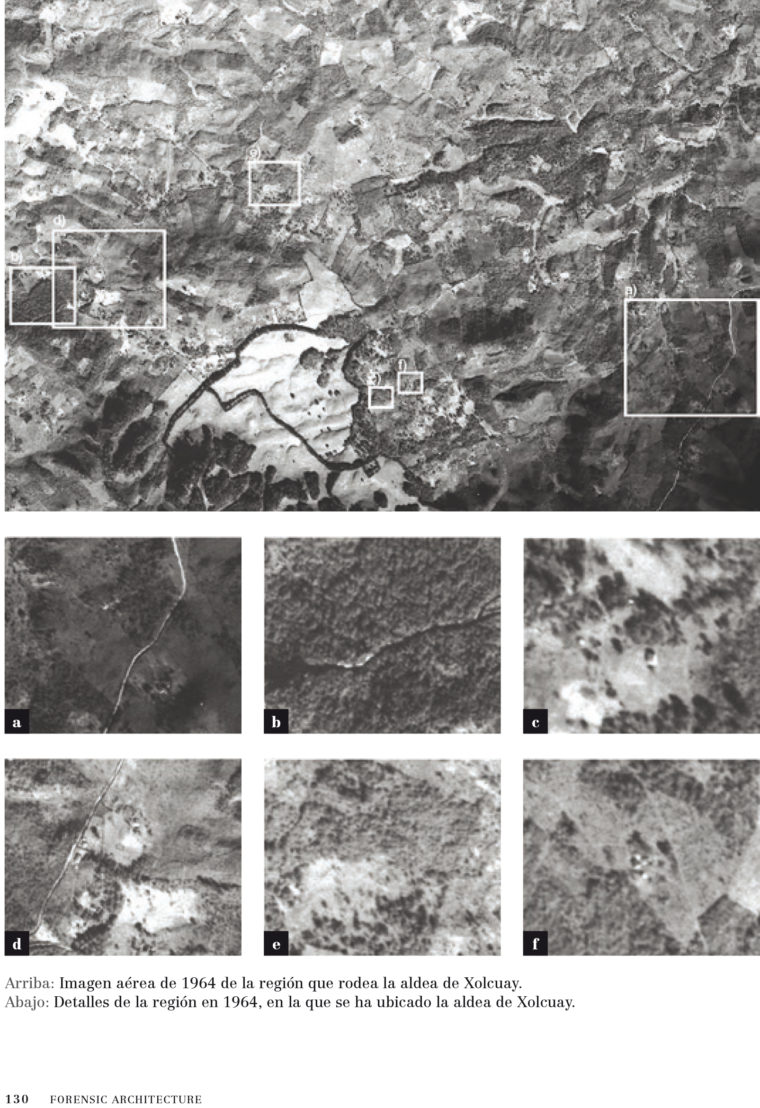

Up: Aerial image of 1964 of the region around the village of Xolcuay. Down: Details of the region in 1964, in which is located the village of Xolcuay

In a different context, but sharing some central issues – like much of Latin America – the dispute for autonomy articulated the conflicts between indigenous people and the former government of Evo Morales at the head of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and was based on claims due to “the identity and cultural imposition of nationalism; the co-optation and persecution of social organizations as an ambition of political monopoly and the promotion of the centrality of the nation state, as opposed to the proposal of the horizontal exercise of plurinationalism; and neo-extractivism and neo-developmentalism as policies of dispossession and ethnocide” (Markaran, 2018). The disputes over the construction of the road in the Indigenous Territory TIPNIS constitutes a paradigmatic example of these claims for a change of political, economic and cultural model, which is referred to in the new state constitution of 2009 (Markaran, 2018); that is, for a search for the development of modes of existential sensitivity that coincides with a desire for another type of society (Guattari and Rolnik, 2013).

Following the line of argument of these disputes, we could read the implications of the three electoral processes set for 2020: Bolivia’s, suspended by the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19, during which Jeanine Áñez exhibits the support of the regional establishment to gain legitimacy; the recent and silent re-election of Luis Almagro at the head of the Organization of American States (OAS), very critical of the Bolivian process and excessively close to Washington; and that of the US administration towards the end of the year, which shows a very active Trump not only in the Caribbean. Macro-political events that highlight the ubiquitous nature of the cultural siege that will have to be faced by those who wish to strengthen not only the processes of autonomic singularization in Bolivia, and that account for another historical process of long standing that extends beyond the region, addressed by the FA collective in the exhibitions and publications of the MACBA and the MUAC.

_____

Comeron, O (2007) Arte y postfordismo. Madrid: editorial Trama and Fundación Arte y Derecho.

Escobar, A (2010) Territorios de diferencia: lugar, movimientos, vida, redes (Universidad del Cauca).

Guattari, F. y Rolnik, S. (2013) Micropolítica: cartografía del deseo. Buenos Aires: Tinta limón.

López Flores, P. (2018) “¿Un proceso de descolonización o un período de recolonización en Bolivia? Las autonomías indígenas en tierras bajas durante el gobierno del MAS”, in López, P. y García Guerreiro (2018) Movimientos indígenas y autonomías en América Latina: escenarios de disputa y horizontes de posibilidad. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

MACBA i MUAC (2018) “Guatemala: violencia medioambiental”, in MACBA and MUAC (2018) Hacia una estética investigativa. España.

Makaran (2018) “Disputar la autonomía. Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia y resistencias indígenas”, in Lopez, P. and García Guerreiro (2018) Movimientos indígenas y autonomías en América Latina: escenarios de disputa y horizontes de posibilidad. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

Svampa, M. (2016) Debates latinoamericanos: indianismo, desarrollo, dependencia y populismo. Buenos Aires: Edhasa.

[1] Reference it is made to the scholarly approach to culture officially extended after the final report of the UNESCO World Conference on Cultural Policies (1982) https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000052505_spa

Ezequiel Filgueira Risso is specialist in Cultural Policy and Management (FLACSO Argentina and Universidad Nacional de Córdoba). Responsible for the Fundación Red ECCCO: para la Educación, la Ciencia, las Culturas comunitarias y la Cooperación; whose programme La Voz Ciudadana and its community art and culture days have been declared of cultural interest by the Legislature of Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires y the UNESCO Chair of Education for Peace and International Understanding. Mail: ezequielfr@gmail.com

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)