Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

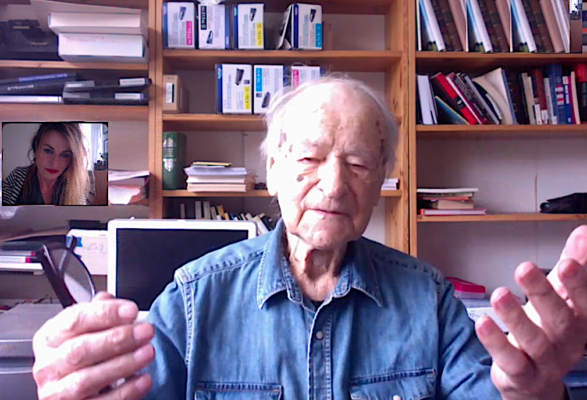

Yesterday 23rdof January of 2019, Jonas Mekas embarked on his final trip. I believe that I am one of the last people to whom he granted an interview, since I had the chance to talk with him last June. When one is in front of a personality such as Jonas Mekas, although it is through a screen and 6000 km apart, it is inevitable to feel devotion and respect. For this reason, this text is a tribute. From Maya Deren, Buñuel, John Cage going through Warhol, the Beat Generation, Pasolini to Susan Sontag, Nam June Paik or John Lennon his career gathers with a constellation of artists that have formed the history of the cinema, the art, the literature and the music of the 20thcentury.

At 4pm CET, 10 a.m. of June the 22ndof 2018 in New York, I met Jonas Mekas through video conference. At his 95 years old, he kept a formidable shape and a lucid and brilliant mind. We talked about the role of the woman in the cinema, the historical cycles of power, the anthological archive in which he was working on in New York and his publication Film Culture. “Publications such as Cahiers du Cinéma or Sight & Sound existed in the sixties in Europe, but in the United States there was nothing similar and my friends needed a vehicle in which they could express themselves. Therefore, my brother and I created Film Culture. Needs are there, always, now too. People are thirsty, although they do not know it. And we have to fight. But doing things, not protesting. I am not interested in placards nor demonstrations, the only thing that changes the world is to look for alternatives and to do things”.

Jonas Mekas (1922, Semeniškiai, Lituania– 2019, New Yok) took his first photo at the age of 17, when the soviet tanks reached his town. He emigrated to New York ten years later. He made his first auto bibliographical film when he was 46. Two years later he founded the Film-makers’ Cooperative. At the age of 83 he created his website. When he was 92 years old, during the Biennale of 2015, he was the president of a colossal installation of his work at a Burger King in Venice. He has become a legend, a voice and a banner of several generations of independent and experimental film-makers. He now appears in the history books as one of the most relevant figures of the cinema.

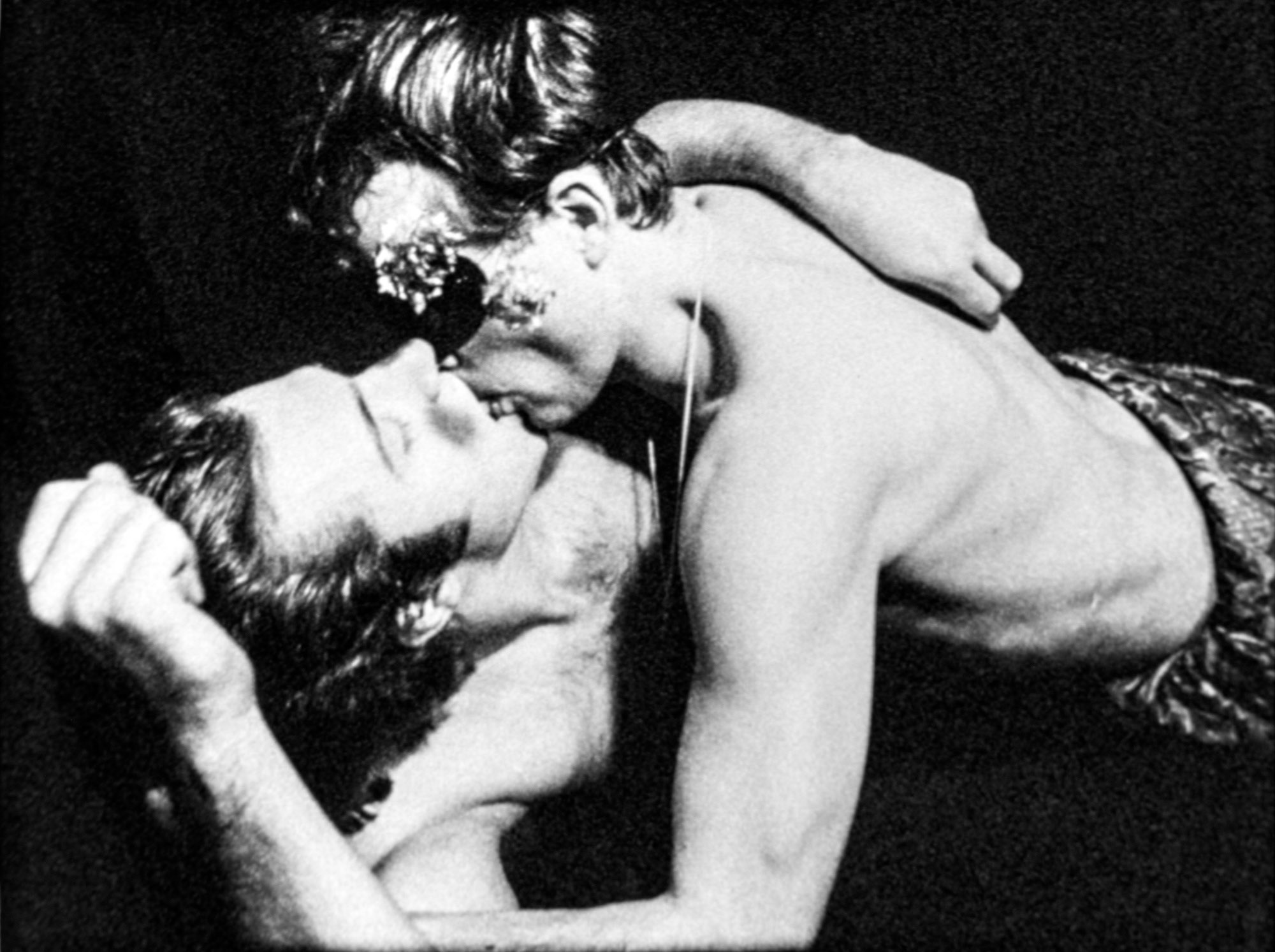

Among his many anecdotes, he explained that he took a copy of the Un chant d’amour, the only film by Jean Genet, from Paris to New York, hidden in the pockets of his raincoat and went through customs with the help of the winner of the British Nobel Prize in Literature, Harold Pinter.

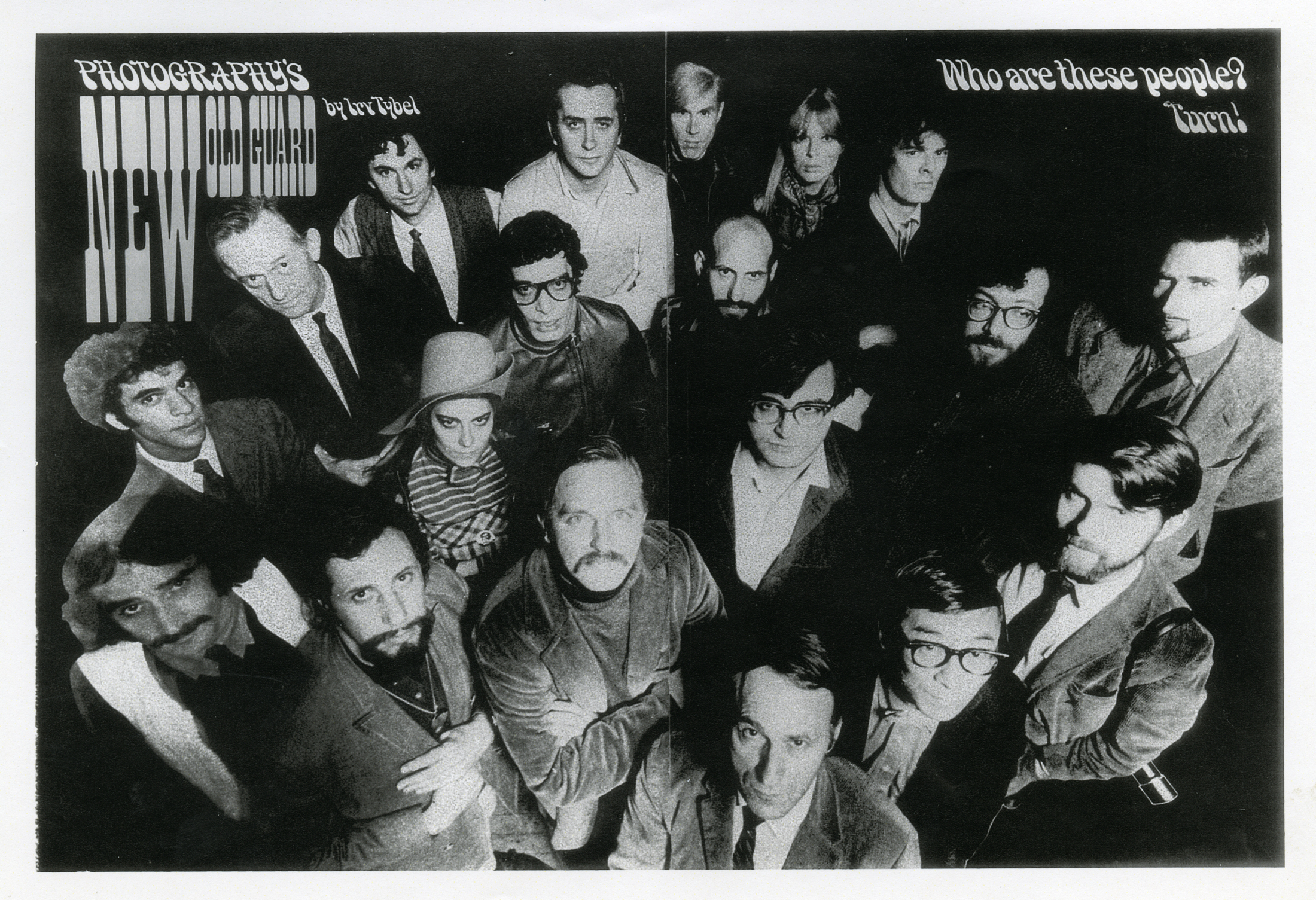

During his life, Jonas Mekas interweaved different disciplines, something very current, we are all involved in many things, especially in the area of culture. He alternated the criticism, the writing, the film production as a cinema editor or programmer, and as he stated, in a very organic way, without effort, a multifaceted person. It seems as if Mekas was being ahead of his time, twisting the story: “When you live, you live the moment, the present, there is no place for history. No one focused on the time in which they live think about making history. Everyone simply does whatever they feel like doing. In my case, I did what I did next to friends and for friends, generating like this a community”.

During his last years, Mekas gave almost all of his public activity to the funding of the project Anthology Film Archives of New York – unique institution that catalogues, preserves and exhibits films of all kinds and that counts with more than forty thousand copies-. “We are raising money and what is curious is that the majority of it comes from artists, not from people of the cinema, these ones ignore us… We hold several auctions to recollect founds with works by Richard Serra, Cindy Sherman or Christo. There is not a single cinema producer that supports us, the only ones that care are Scorsese and George Lucas. The library will raise and digitalize all books, magazine collections and publications that we have gathered. The truth is that I cannot think of anything else. I do not do this for myself, I do it for the cinema, so that everyone has access to these enormous documental collections, that date back to the twenties”.

Just in the last year, in the cinema industry, the feminine voices have raised and their echo has spread other feminist movements around the world. I was interested in the historical view that Mekas could give about the role of women in the cinema: “Minorities, such as women, and alternative groups, started in the field with the video, mainly because it reduced the process of production. It was not so masculine anymore”. According to Mekas certain energy is needed, “the male energy”, to become the director of Hollywood. “At the beginning of the seventies, many film-makers’ women appeared. Until then, the only known ones were Leni Riefenstahl or Shirley Clarke, both strong women”, continued.

With regard to film types, he said that the documentary and the avant-garde poetic cinema are the most feminine ones. “There are not still a lot of women in the novelistic field”. Mekas calls narrative films, “novelistic” and he distinguishes them from the underground, not commercial and poetic, that he classifies as “personal cinema”. In fact, many of these last ones have resisted to the test of time, thanks, greatly, to his own efforts as a critic, programmer and stockist. “In some sort of “personal cinema” there are many women. Especially nowadays, that we have different kinds of cinema such as gay and lesbian, American Asian, black, Native American, etc.”, he said.

Half century ago, in a conversation with Pasolini collected in Scrapbook of the Sixties, Mekas already predicted a future marked by cameras and images, as a consequence of the price reduction of video cameras. “We will take away the cinema from the industry and we will give it to homes. This is the truly meaning of the underground cinema”, said Mekas to Pasolini. Remembering him this quote, Mekas said that Pasolini answered much better: “A lot of houses have a typewriter and this does not mean that they write better and faster. Cameras are like a pen in our pocket, another tool to communicate, but not necessarily better”. Exactly what happens today, everyone has a high definition camera in their mobile phone, contributing mainly to a saturation of images without any contribution in the majority of cases.

Going back to the issue of the democratization in the production of films, we venture to talk about the distribution: “The current distribution also helps women. Many directors that produced films between the thirties and the sixties could not show them. Nowadays, with the video and the digital cinema, more people can be reached. Moreover, they can be shown through the Internet, what also facilitates the local initiatives of the cinema”.

About the Internet and our society highly technologized, where corporations such as Facebook, Google or Instagram are already distribution channels and leak the content that forms our subjectivities, I asked him for his opinion in the effect that the social media has in the independent forms of production and distribution of culture. The answer of Mekas was: “With the Internet, the world is like a big city, but inside the city there are neighbourhoods. The society in general is uniform: reads, eats, wears and consumes the same things. I think that there are not a lot of differences between the sixties and now. In the big city small groups exist, minorities that are known very well among them. Do not worry for this big corporations that dominate the culture and the senses. Today they are here, but tomorrow they will be gone, it is a big dough from scratch. Small minorities can kill big monsters. Minorities and animals in danger of extinction have always existed. Three thousand years ago and now. During the medieval age there were jugglers, puppeteers, story tellers and poets, troubadours have always existed. No one takes us seriously and we do not care. We are here to celebrate the creation; we are not here to be businessmen nor to destroy the planet. We are invisible, but we are necessary for what human being means”.

And with this inspiring declaration, I let Jonas Mekas enjoy his breakfast on the other side of the ocean.

María Muñoz-Martínez is a cultural worker and educator trained in Art History and Telecommunications Engineering, this hybridity is part of her nature. She has taught “Art History of the first half of the 20th century” at ESDI and currently teaches the subject “Art in the global context” in the Master of Cultural Management IL3 at the University of Barcelona. In addition, while living between Berlin and Barcelona, she is a regular contributor to different media, writing about art and culture and emphasising the confluence between art, society/politics and technology. She is passionate about the moving image, electronically generated music and digital media.

Portrait: Sebastian Busse

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)