Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

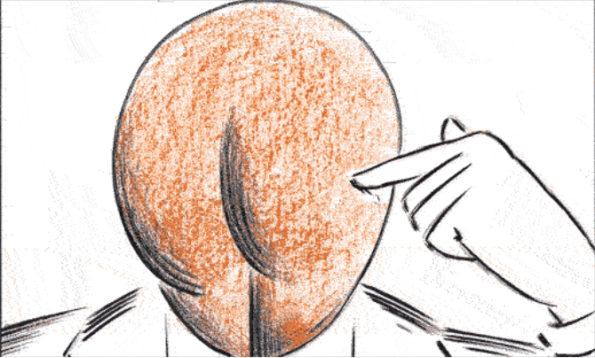

El Roto is known for his daily satirical (but not funny) illustrations in the newspaper El País. Who is not quite so well known is Andrés Rábago, the author hiding behind the pseudonym of El Roto. Hospitalet’s cultural centre, the Tecla Sala, recently dedicated an exhibition to him,El Roto, OPS, Rábago: A journey of a thousand devils (and a couple of angels) covering his three most distinguished phases since he began his career in the mid sixties last century.

Does the act of incorporating a popular genre, such as satirical cartoons, within an institutional space, alter the possible impact of the work? That is, does the museumification of the work cause it to lose its original meaning? Or on the contrary, does it convert the space into one where there is room for dissension?

Depending on the era, Rábago has been closer to surrealism (during the dictatorship), or more caustic (the facet of El Roto) but his work has always remained in direct contact with reality, his source subject, and an insistence on transmitting an engaged social message over and above other questions. Rábago states in an interview that could be seen on one of the screens in the exhibition, that he wants to forgo his ego, invent a language, and is just trying to transmit a message. I find his work interesting for its critical social charge but, above all, for its discursive clarity.

In an interview in 2004 with Ima Sanchís in La Vanguardia, Rábago said: “What El Roto tries to do is to help focus on the nonsense so that it makes sense. We live in a nebulous world and satire helps to bring it back into focus. It doesn’t resolve anything, but it helps us to know where we are and who we are dealing with…” This description of his work is a good summary of how Rábago strips bare the existing power relations leaving their entrails out in the open.

Humour is often used as an expressive recourse and has been practically since the existence of a collective critical conscience. Satire is a tool that makes it possible to go that bit further when criticising the establishment, when one isn’t joking. Humour serves as a means of catharsis, one that is particularly useful in moments of crisis or censorship, and when graphic it has the virtue of being easily understood by all social strata.

This is why politicians fear this medium so much, for being the one that most threatens the status quo, much more than text. In Drawn To Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons, Chris Lamb explains some of the most noteworthy cases of politicians reacting to cartoons, such as when satirical cartoonists have been and are imprisoned, or when politicians have committed suicide having appeared in a satirical cartoon. And because they fear it, they try to neutralise it.

The fact of incorporating social critical humour into public, not popular, institutions (particularly compared to the magazines, seminars and newspapers from where they originate) as in this case, Tecla Sala, or even the Real Academia Española, through academics like Wenceslao Fernández Flórez and Mingote, can inconveniently neutralise their critical and political charge.

By being totally admitted into the system, is there a loss of the very necessary dissension that it could provoke? The smile that appears when one identifies with El Roto‘s way of thinking, or, the opposite, the feeling of disgust and impotence that many times his work emits, does it really manage to create this confrontational space within the institution? Do the underlying relations of power that it reveals translate into a greater transparency of the power relations beyond the cartoon itself?

In the last ARCO fair, Francesc Capdevila, ‘Max’, was the protagonist of El País‘s stand. The insertion of popular culture into that of the elite is the very subject of his work. But what consequences does this insertion have? Who or what benefits?

Raquel Machtus is a nomad by birth. Aside from her enthusiasm for discovering new places in the world, she is also interested in nomadism in situ, that is to say exploring and going deeper into the as yet not established connections between elements within a context. In addition, she thinks that art, analysed through all its facets, offers very interesting perspectives on this nomadism. She’s proposing to go into them in more depth.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)