Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

I start to write but immediately look up, a reflex movement that gives me, as it does other people, the feeling of being able to organize my ideas. In front of me, the bedroom window is a cutout, a frame filled with light. As in a movie screen (a window open to the world), the outside world becomes geometrical, normalized, ordered, and classifiable. On my computer, the effect is even greater, as the windowsthere are not only multiple but also dynamic, the stable screen shattering into a burst of options, commands, and tabs[1]I like to think about the continuity of these metaphors linked to the eye and vision in digital media.. Where to look?

Despite these first impressions (somewhat exaggerated, perhaps, but hopefully they justify my argument), the contemporary use of the split screen, which has become popular in recent times due to the proliferation of social activities on videoconferencing platforms, is far from new. On the contrary, we could trace a genealogy of this device within the audiovisual field, including experiments as early as Abel Gance’s film Napoleon (1927) and his Polyvision system, the daring television experiment Ubu Roi (1965) by Jean Christophe Averty, or the multiple configurations of expanded film that began in the 1960s[2]A deep work of historicization and analysis of these cases can be found in Weibel, Peter, “Expanded Cinema, Video and Virtual Environments.”

In this sense, video art is one of the sites where this device has been experimented with in the most challenging way, linked at first to combating a certain transparency effect of the television medium. If newscasts on television try to comfortably juxtapose two simultaneous scenes in time occurring in distant spaces (as in the classic studio/outdoor shots), many works creatively expose the artificiality of this construction. Thus, a paradigmatic example may be the funny “toast” between the journalist George Plimpton from a New York studio and his French correspondent at the Center George Pompidou in Paris during the first minutes of Good Morning, Mr. Orwell (1984) by Nam June Paik. Far from diverting the gaze towards the eyes of the presenters in the classic configuration of the television split screen, Paik places the line of contact/border as the protagonist of this celebratory gesture, highlighting the adulterated condition of that alleged coexistence.

Nam June Paik, “Good Morning, Mr. Orwell”, 1984

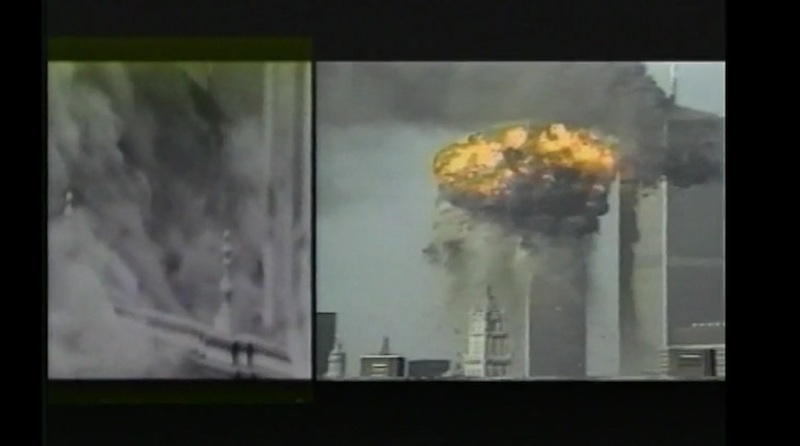

On the other hand, in Latin American the video 11 de septiembre (2002) by Claudia Aravena presents a different use of the split screen, not merely a question of juxtaposing two simultaneous events on the same surface but of bringing together on the screen two distant events in time. In a provocative gesture, Aravena assembles images of the fall of the Twin Towers in New York in 2001 with the coup against Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973, two events that, curiously, occurred on the same day 28 years apart[3]Also, strikingly, the Twin Towers were inaugurated in 1973, just five months before the coup and assassination of Allende.. Accompanied by fragments of the texts of Marguerite Duras in Hiroshima, Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959) and Allende’s last speech in the voice of the artist herself, the video exposes two halves of the screen that shift the limits between the two, as if the Chilean events must struggle to enter universal history, too easily and with arrogant invisibility, as history tends to focus on the events that occur in the most powerful countries.

Claudia Aravena, “11 de septiembre”, 2002

However, I sense that underlying these reflections on the extended use of the split screen is a more relevant issue (though not for that reason any less hidden) linked to the possibilities of re–actualizing a dynamic of the gaze. In the case of the images we are accustomed to living with and that are today the focus of this reflection (unlimited grids inhabited by talking heads within our videoconferencing platforms), the difference resides in the inclusion of the spectator/user within the image,[4]Curiously, the first fantasies around the possibility of conversing with a distant person while his image could be seen referred to an idea linked to the cinematographic screen, as can be seen in the … Continue reading which exists on the same surface as others. Far from being merely an anecdote, I suggest that the metaphor of the windowthat opens out onto the world, which has served as the epistemological basis of cinema, could today be more appropriately replaced by the metaphor of the mirror.

As we know, audiovisual machine images[5]See Dubois, Philippe. “Máquinas de imágenes: una cuestión de línea general”(Image Machines: A General Line Question), in Video, Cine, Godard, Buenos Aires, Libros del Rojas, University of … Continue reading have been direct heirs to the Renaissance perspective and, therefore, of the organization of space from the point of view of a single and stable subject (normally male, white, educated, and European), a period that historically and geopolitically makes the Renaissance coincide with the genocide in America and the witch hunts in Europe during the 15thand 16thcenturies. Likewise, as Mary Louise Pratt examines with solid documentation in her fascinating book Imperial Eyes: Travel Literature and Transculturation, the regimes of systematization, production of order and global unity of nature within science, travel writing, and the cartographic reliefs of the 18thcentury would also be directly related to the European imperialist project: “as an ideological construct, the systematization of nature represents the planet as appropriated and reorganized from a unified European perspective” (Pratt 2010: 73).

In this context, audiovisual machines have been used on a mass scale in order to (re)produce the image of a stable, ordered, classifiable world. However, and despite the endless proliferation of images, the multiplication of screens within screens, we seem to be approaching an exhaustion of the gaze, as if the increase of images within other images has led us to the height of absurdity. Paradoxically, as if in front of a mirror, this is an eye that can only look at itself, a selfiein real time that wants to disguise itself as a dialogue or a communicative event. In contrast to this effect, I find very suggestive Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui’s question in her Sociología de la imagen: miradas ch’ixi desde la historia andina (Sociology of the Image: The Ch’ixi Gaze of Andean History), about “[…] how Cartesian ocular-centrism could be decolonized and the gaze reintegrated within a body, within the flow of living in space-time, which others call history.” (Rivera Cusicanqui 2015: 25). For the author, if the gaze has been organized around the eye as the governing organ, we need to free ourselves from its ties in order to reinsert it into a dynamic that includes the body, the mind and various dimensions of experience.

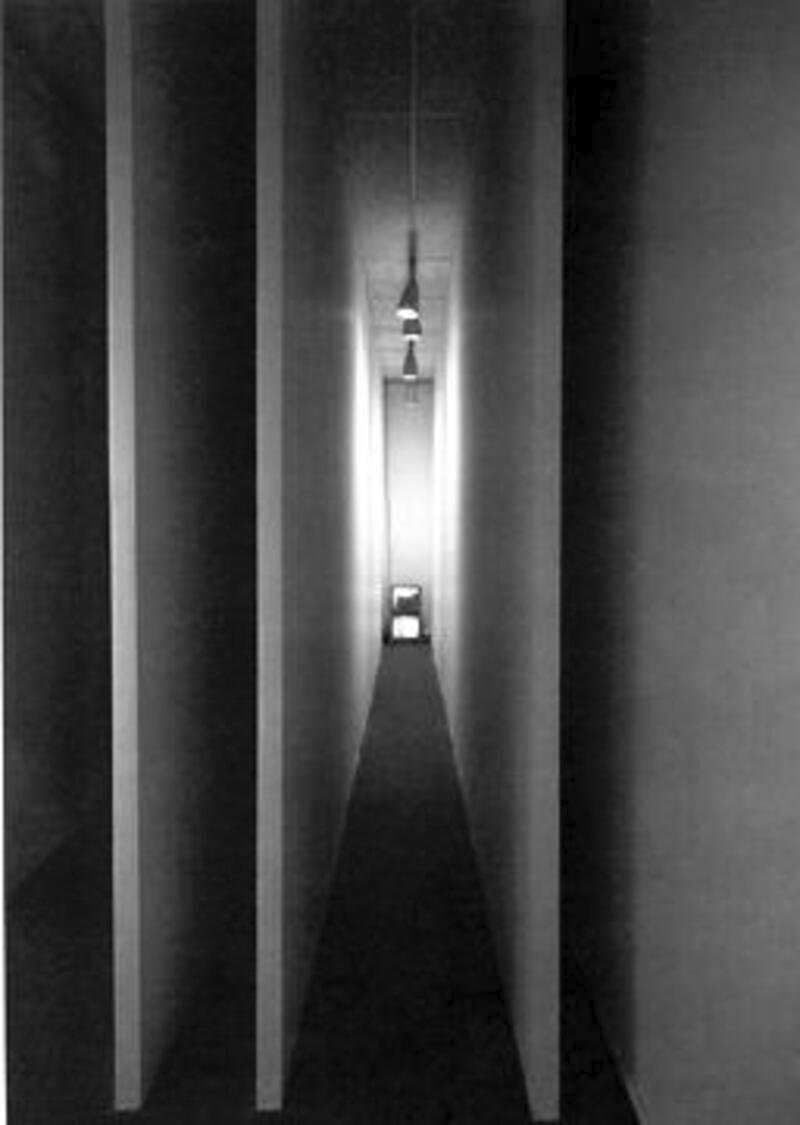

While rereading this last sentence I thought of Bruce Nauman’s Live Taped Video Corridor (1970) as one of those works that inscribes an indelible mark on the body. I go down a hallway and at the end are two monitors, one above the other. The installation is simple, with one of the monitors showing the image captured by a camera in front of me, and the other that of a camera located behind me. But the effect is overwhelming: progress is relative and space/time coordinates become distorted. Perhaps, more transcendentally, my image is no longer mine. I become another while I see myself, and in that lies a potential transformation of modes of vision and communication simulations that challenge the homogenizing multiplication of screens. Perhaps from these experimental, provocative, and unique works, we will be able to go through the window without returning to the mirror. In the end, the initial question could also be reformulated: only look?

Bruce Nauman, “Live Taped Video Corridor”, 1970

(Cover image: Claudia Aravena, 11 de septiembre (filmstill), 2002)

| ↑1 | I like to think about the continuity of these metaphors linked to the eye and vision in digital media. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A deep work of historicization and analysis of these cases can be found in Weibel, Peter, “Expanded Cinema, Video and Virtual Environments.” |

| ↑3 | Also, strikingly, the Twin Towers were inaugurated in 1973, just five months before the coup and assassination of Allende. |

| ↑4 | Curiously, the first fantasies around the possibility of conversing with a distant person while his image could be seen referred to an idea linked to the cinematographic screen, as can be seen in the illustration of Edison’s Telephonoscope by George Du Maurier (Punch Magazine #75, December 9, 1878.) |

| ↑5 | See Dubois, Philippe. “Máquinas de imágenes: una cuestión de línea general”(Image Machines: A General Line Question), in Video, Cine, Godard, Buenos Aires, Libros del Rojas, University of Buenos Aires, 2000. |

Mariela Cantú (Argentina, 1981) is an audiovisual preservationist, artist, curator and researcher in Audiovisual Arts and Media. She holds a Master’s degree in Preservation and Presentation of the Moving Image (Univ. of Amsterdam) and a degree and professor in Audiovisual Communication (Univ. Nacional de La Plata). She is the creator of Arca Video Argentino, Archivo y Base de Datos de Video Arte Argentino, and her area of research focuses on the preservation of magnetic video.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)