Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Thierry Geoffroy (born 1961) is a Danish-French conceptual artist who that uses a wide variety of media, including video and installations, often in collaboration with other artists. Geoffroy refers to his work as “format art”, since the format of the artwork is the artwork. The formats generally involve many participants and are designed to investigate social psychology (e.g., conflicts, collaboration).

‘Today, before it is too late’, I meet Thierry Geoffroy/Colonel for the first time on Skype, he is in Copenhagen (11am), and I am in London (10am). I soon feel Thierry is able to ‘root you in the now’. One thing leads to the next and, we are soon somewhere else. This interview reflects his work: ‘thinking in the making’.

Right now, what are you focused on?

An exhibition at SABSAY Copenhagen, “Always Question the Structure” #documentaSCEPTIC. It questions pigment, canvas, frame and venue but also, more importantly, the structure of the Biennale, fairs and the system behind the artwork. This season, and for the next two months, I will question the structure of the Venice Biennale and Documenta in Athens and Kassel.

Talking about questioning, is this best done from inside or outside the institution?

At Manifesta 8 I was a commissioned artist and yet I still questioned the actual biennial from the inside. My BIENNALIST project was officially part of the exhibition, and people paid attention because I had a space. When you are outside you are seen as disruptive or you aren’t taken seriously.

Is your critique aimed at the public or at artists?

My interest is to reach the public. Documenta has nearly a million visitors. At Documenta I question the relationship between art and the weapons industry. The exhibition is ten metres from one of the biggest weapon producers. Most people do not know this, so if the event wants to reflect the world, the public should also reflect on this. Documenta is connected to colonialism but tries to create an illusion of debate: contemporary art is the botox of capitalism.

What, for you, is an emergency?

Many things! The new law in Denmark against xenophobia. Today my emergency asks why are people so asleep. The project is to train the “Awareness Muscle” in as many people as possible.

How come people are so asleep?

There are a number of sleeping pills. Spectacle society, cinema, TV, entertainment… Politicians are one form of entertainment, contemporary art is another. People think they do not have to make an effort. Instead of moving or being critical, they go and see an art show. At Documenta Kassel you see a kind of filtered exhibition. You think you are connected to what is happening in the world, that you know about the refugee crisis and what is happening in Syria but you are given an illusion of caring. You are going to reflect and cry a bit. This is not enough. Instead of waking up, you fall asleep. Art these days has this effect.

What kind of effect?

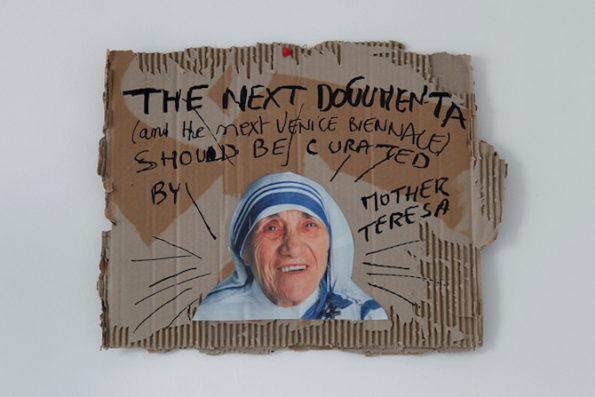

You think you are part of research into how bad the world is and what can be done about it, but it is all fake. Those exhibitions make us believe that they care about the real problems, they try to contribute to a debate, but it is quite the contrary, it creates apathy. They are preaching without waking us up. At both the Venice Biennale and Kassel they were saying we live in a world on the brink of exploding, we have to get it together and do something about it. It is a political statement and we have to ask if what they are telling us is fake or not? How many people take action after hearing it? There is a distance between what is said and what is done. They speak like Mother Theresa but do not act to help anybody. In the meantime, they occupy the physical platform and things that should be done do not get done because people cannot put their attention everywhere

Why are biennales trying to be Mother Theresa?

I do not know. They did not need to do it. Maybe it attracts tourists. On Facebook, most people want to look good and sound good. It is like thinking that if you watch the news each day you will be a better citizen, more informed, more empathic. It is the opposite! Watch too much news and you become scared. Maybe it is a strategy to steal the humanist platform and fill it up with air, to occupy the space of other revolutions… To pretend they are the revolution when in fact they just want to entertain. Stealing the stage is perhaps a conservative strategy to create an illusion of humanism. What do you think?

The “do good” attitude is a trend. When I see refugees in an art show I wonder, is it genuine, do they care?

Maybe it is a diversion. The arts pretend to care about an issue, but it stops us from looking at it from another direction. We need to question their motives. I made a slogan at Kassel: “Is Documenta in Athens to sell Kassel’s tanks?” because at Kassel’s factories they make tanks to repress protests. It is a Kassel speciality. They have four factories in the centre of Kassel and a second group of factories next to Athens. Why are they in Athens?

Are people afraid to offer opinions in public?

People question things but are afraid to show it, they are afraid of repression. If they have an opinion at all, it is very mainstream. Other ideas are seen as having a potential for repression. For example, when people post pictures of American police spraying protestors. If you show sympathy for these people, you might be the next victim. People are afraid to show what they feel. People who really want to change things do not make Facebook event pages. Opinions are hidden and self-censored. It happens with artists too. For example, the work of Hans Hacke at Documenta: there you had an artist who was able to be sharply critical, and suddenly he does a work that is ‘nice’. What happened?

Is visibility some kind of censorship?

Yes. There are visual platforms like Documenta and there are other, invisible platforms. Within the visible platforms, there is a lot of self-censorship, with people endeavouring not to lose customers. We may think we have freedom of speech, but one form of censorship is not to show opinions contrary to the mainstream. If you make a great book and it never gets distributed, your book is invisible. If you make great art and you are not seen in the right places, you are invisible. It is a kind of censorship.

You wrote on a tent “The emergency will replace the contemporary”.

I was predicting the future. If a museum goes underwater because of climate change suddenly you will not have contemporary art so that the museum can be a hospital, for example. The question of the emergency will be so big, contemporary art will be replaced. Here things move slowly, but elsewhere, they move very quickly. At the Venice Biennale 2013 I was part of the Maldives pavilion. In 10 to 30 years, the whole country will be underwater. If you have a country that disappears under the sea due to climate change, we cannot speak of contemporary artists in the Maldives.

What is your call to action?

It is about recruiting, and creating an open platform. Since I started the Emergency Room format about 500 artists have been involved, so that they can think about what an emergency is and express it. If I do a Critical Run, people can be part of it. Instead of being in front of the TV, they can actually debate. They can sweat and share worries and visions, instead of just eating ice cream. I have another format called Techno Rave. You go to a rave and debate. I’ve tried to find methods to activate criticality these have a scenario, a method and potential participants. I call them formats because they have certain rules and can be activated globally. It’s possible to have several Critical Runs on the same day, for example in Barcelona, Siberia and Sydney. The idea is to multiply criticality and awareness training.

How effective is it to debate while running and sweating?

To run and debate at the same time is not cool it’s embarrassing. The first step is not to be frightened of this embarrassment. There is no time for chit chat. People on the run push the conversation. So it is a bit pushy. Thoughts come out during the run and participants hear something new and start thinking, saying new things and developing new ideas. Sharing opinions at a dinner is easy but if you run, there is a certain amount of friction. Also, in an emergency, you have to run if you need to save someone from sinking. Forget about a plastic glass, a smoothie, a cigarette or walking cool or indifferent.

What is the goal?

A moment of clarity. At some point, after training the Awareness Muscle you discover something that will become clearer. Later you keep looking and thinking. The run kick starts thinking. As I said, it is about honing an Awareness Muscle, a way to become “addicted to”, criticality. If participants train their Awareness Muscle ten minutes a day, after a time, they improve. They watch the news and can understand how they are constructed as propaganda tools. Do it ten times and you become an expert.

What do you do with the outcome?

Everything is recorded. Things people say might be extremely interesting. The final video is a serial of fragments and people can hear the different positions of meaning around the same debate. Once I did a Critical Run in Stockholm commissioned by Moderna Museet. They invited art critics and the debate question was: “are art critics critical”. It was called Art Critics Critical. Surprisingly most of them heard it afterwards and said: No, critics are not critical. It is interesting that art critics do not think they are critical. I would never have got this result after a three-day seminar where people sit and debate. It is interesting for the public, but it is also interesting for critics, because if they are not critical, they can reflect on that.

Does being critical affect people’s lives?

I think it makes life more miserable. The more you know the sadder you get. You are happier when you know less. Now I know about these weapons factories in Kassel I can no longer see Documenta in the same light, somehow it is better not to know. But we are in an age of huge problems, we have to be responsible and analyse the problems and try to solve them, not ignore them.

Your vocabulary develops new words like ultracontemporary, biennalist…

It is an attempt to order chaos, to condense ideas… Also because the old words, like ‘happiness’, ‘love’, have been misused. If we want to express more than marketing terms, we must create new words. Ultracontemporary came from looking at contemporary art, like for example at Documenta, which is more antique than contemporary. If I want to express closeness to the now I need to create new words. If I do an Emergency Room and invite other artists, I am extracting. I create a platform, they offer opinions, and I extract opinions. For the Emergency Room I made a dictionary (http://www.emergencyrooms.org/dicti…). Artists use a vocabulary of colours, forms or textures, but you can also express yourself in words!

Any new “Art Formats” coming up?

Yes, one Extracter format just started in Oslo at the IKM museum. It will last five years. The subject is xenophobia and prejudice. I am going to extract opinions and evidences about xenophobia from 50,000 Norwegian people, including immigrants. I will extract data from mobile phones; it’s going to be huge. I have many more formats (http://www.emergencyrooms.org/forma…)

How did you evolve to work with the here and now?

I change all the time. I am sensitive. Certain things are too much for me, I get affected. Formats are concepts with people but because they involve people and emotions, they connect to what is going on, to the now. Some artists are supersensitive. They are “ecorché“,as if they have no skin. Think about the tsunami. Let’s say while people are on the beach the animals run away as they have a sharp perception of danger. Artists are the same. Artists work a lot by intuition but we cannot know what they think if they do not show it in time. I try to find a system to find out what they think in real time and express it. If Spain wants to bomb Iran tomorrow, and an artist is not a writer or graffiti-artist, how do they react today through art and show it to the public? If the work remains unseen for ten years, it’s not going to be in the debate. That is the strategy for the Emergency Room: to show artists responding to the emergencies here and now.

Even then, is it too late?

Once, I hoped to create change. Now I am sad that it may be too late for some emergencies. What do I do? Stop? Be sad, angry, commit suicide? What next? So I am thinking about how to integrate this “too late” into work that aims to solve emergencies.

What is the difference between the role and the function of an artist?

The function is when artists are used as tools to increase sales of beer or cars, to clean embarrassing history, or help cultural colonialism. If they don’t want junkies here, for example, a bank commissions Pippilotti Rist to make public art. The role or duty of a citizen means that when artists see something strange they should raise the alarm. Artists are experts at detecting alarming issues and it could be their role.

If you were not an artist, what would you be?

I studied medicine. I wanted to be a psychiatrist. I wanted to create a psychiatric hospital on a train. I should have, because a doctor is more useful to society.

Cecilia Martín is the arts and culture brand strategist. Cecilia is based in London and has founded the Cultural Connection (CC) network-agency that helps museums, art galleries, biennials, orchestras, auditoriums and universities around the world to break the mold and find new ways to connect with their public. Cecilia is a professor of Communication and Branding in Art for the Master of Contemporary Art of the IL3 at the University of Barcelona.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)