Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

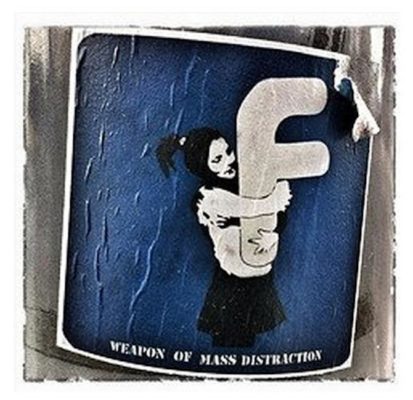

Participating in social networks offers the advantage of detecting patterns of behaviour that otherwise would pass undetected. Ultimately it’s true that the symbolic gratification to be found there is greater the more disinhibited the user turns out to be. A radical position with regard to Facebook principally contains two forms of being: a state of ON or OFF. Recently my attention was drawn to the display, by an artist, of a critical review by a critic in an international magazine. It wasn’t that the artist posted the link to promote it, something fairly common, so much as what was being shown was the photograph of the review, the reliable proof of its appearance in the media. It’s worth stopping a moment to calculate the effects on art criticism that derive from this self-promotional act. The sequence is a familiar one, but it’s worth repeating as a reminder of the editorial function: the critic has selected, later he has made a proposal, his proposal is accepted, the critic has written and what is written is printed. Once published, the review reaches the artist in question, who publishes it on his “wall” not so much as a text but more as an image. Reification? Would he have published the “image” if what the critic had written rather than being in sympathy transmitted a negative judgement? Yes or no?

Not so long ago Boris Groys commented that what ended up counting in criticism wasn’t so much a positive or negative critique of the work in question, as the fact of whether something had been written or not. No longer a “yes/no” or “more/less” in its judgement so much as, according to him, a point has been reached where the first and final form of judgement is the digital code of “one /zero”. Mentioned or not mentioned. The principal judgement is established in the decision of whether to write about one exhibition or author, or not. What counts are the “ones”, as any type of negative criticism is de facto neutralised by the fact that it is a “one”, that something has been written and published in the sphere of circulation that criticism has become. What’s more, with the decline of any form of judgement in criticism, everything published is a large ONE. This sphere of circulation, the supply and demand of criticism, is a form of market that we all participate in. There is nothing an artist or gallerist laments more than if nothing has been written about an exhibition, while the “public office” that criticism has become (according to Groys) has its best from of representation in the press offices of private galleries and public museums, for whom the fact that something is published often already compensates for the investment.

In the now famous exhibition of Seth Siegelaub, “January 5-31, 1969”, Joseph Kosuth “dubbed” his participation with a self-interview with the critic Arthur R. Rose, a pseudonym for Kosuth. He very rapidly understood that with the work of art reduced to information, publicity became the instrument that would supplant the appreciation and comprehension of art previously conferred by criticism. The work of art no longer needed to inscribe itself as a unique object as any medium can be a “box for the ideas of your choice”, guaranteeing a rapid advance and wide distribution. Kosuth contributed to the definition of the term “conceptual art” while at the same time being a pioneer in publicity, or one of the initiators of a model of artist sustained in an unprecedented careerism. Through Seth Siegelaub (proto-curator, entrepreneur and publicist), conceptual art managed to unite criticism and publicity by paying as much attention to press, promotion and publicity as to the actual content of the exhibitions.

It was a question of time before in the future criticism and publicity would become indistinguishable or carriers of the same value. This already occurred in the work of Kosuth, Second Investigation, I. Existence (Art as Idea as Idea), 1968, presented in the aforementioned exhibition. Here the artist bought space in different newspapers and art magazines where he published dictionary definitions of the word “existence” in the form of advertisements. In the exhibition he hang these same pages containing his work with the masthead of the printed medium above each cutting. The message launched by Kosuth was a forceful one as for the first time it equated the places where art is represented (the advertising section and the pages of critical reviews) with spaces for sale.

Since then, criticism, advertising and institutions maintain an idyll that has merely been reiterated. It’s not surprising that what followed was that criticism began to seem increasingly like press releases. The difference between the conceptual artist of the incipient society of information and the contemporary artist is that for the latter publicity has become natural without being aware of the critical “innovation” of the former. The appearance of art criticism in Facebook ought to serve to question the function and use of publicity.

Peio Aguirre writes about art, film, music, theory, architecture and politics, amongst other subjects. The genres he works in are the essay and meta-commentary, a hybrid space that fuses disciplines on a higher level of interpretation. He also (occasionally) curates and performs other tasks. He writes on the blog “Crítica y metacomentario” (Criticism and metacommentary).

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)