Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

Why has the creation and research of the occult in art become so popular nowadays? Is it a nineteenth-century revival, or has it always existed, but just never acknowledged by traditional institutions before? I often side with the latter. The occult in art has always been my main research focus since the start of my academic career; primarily the intersections of Spiritualism within nineteenth and twentieth-century photographic practices and mourning customs. But what has sparked this recent interest in this subject area among myself and fellow artists, researchers, and historians, etc.? In a recent statement made by curator, Cecilia Alemani, on the theme for the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, she states that:

“The pressure of technology, the outbreak of the pandemic, the heightening of social tensions, and the looming threat of environmental disaster remind us every day that as mortal bodies, we are neither invincible nor self-sufficient…” [1] The Milk of Dreams, Cecilia Alemani, 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy. https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/statement-cecilia-alemani.

It is this pondering of one’s own mortality driven by technological accelerationism and direct confrontation of death that drives both one’s fears and curiosity of / in the unknown and towards the exploration of the occult.

The exploration of what constitutes time and space has been an abiding subject since the beginning of recorded history, with a profound interest rooted in the nineteenth-century that continued into the turn of the twentieth-century to contemporary times. It became not only an discourse of philosophy, but crossed over into the realms of scientific experimentation, mysticism, and art.This was due to quickly developing media and communication technologies during the Second Industrial Revolution that revived interest in metaphysical texts and gave rise to belief systems like Spiritualism. With technologies that either suspended time visually, or allowed people to communicate with others almost instantaneously through coded electrical messages, this new belief system developed as responses to these new modes of communications. Not only did it develop in response to technological advancements, but also social movements and events at the time as well, like high infant mortality rates due to epidemics across the world and Women’s Suffrage.

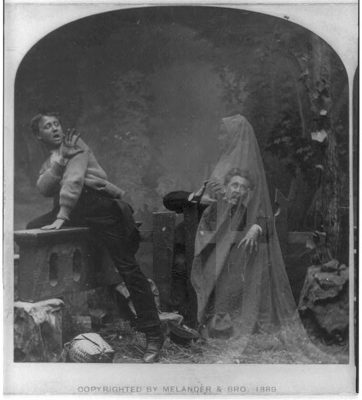

The Haunted Lane, ca. 1889, fotografía

Spiritualism, like the suffragist movement, gave women a voice in a time period marked by strict and repressive social practices that controlled even the expression of grief. The Modern Spiritualist Movement is often understood to begin the same year as the Suffragist movement in The United States, in 1848. As Barbara Goldsmith writes, “Spiritualism and women’s rights drew from the same well, both were responses to the control, subjugation, and repression of women by church and state” [2] Barbara Goldsmith, Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1998), 48. . In the rural town of Hydesville, New York, two sisters, Maggie and Kate Fox, were reportedly able to communicate with the ghost of a dead peddler through rapping on the surfaces of their room. These “‘Rochester Rappings’” may be considered the first forms of automatic writing, although no pencil or paper were used. For many, the sisters’ abilities and the movement that was rising around them was the confirmation they needed that there was an afterlife, and that their lives on Earth still meant something. It was also a chance for people to get closure with loved ones who died an untimely death, or off in the war where families never even got the chance to have a proper burial for their deceased. This is also where Women’s Suffrage became involved, with many key figures of the movement labeling themselves Spiritualists as well. Suffragists had stated how Spiritualism had been a religion that was “…committed to fostering female leadership” and was the “only religious sect in the world…that has recognized the equality of women…” in a 1880 text, The History of Woman Suffrage.[3]Anne Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), 2-3.

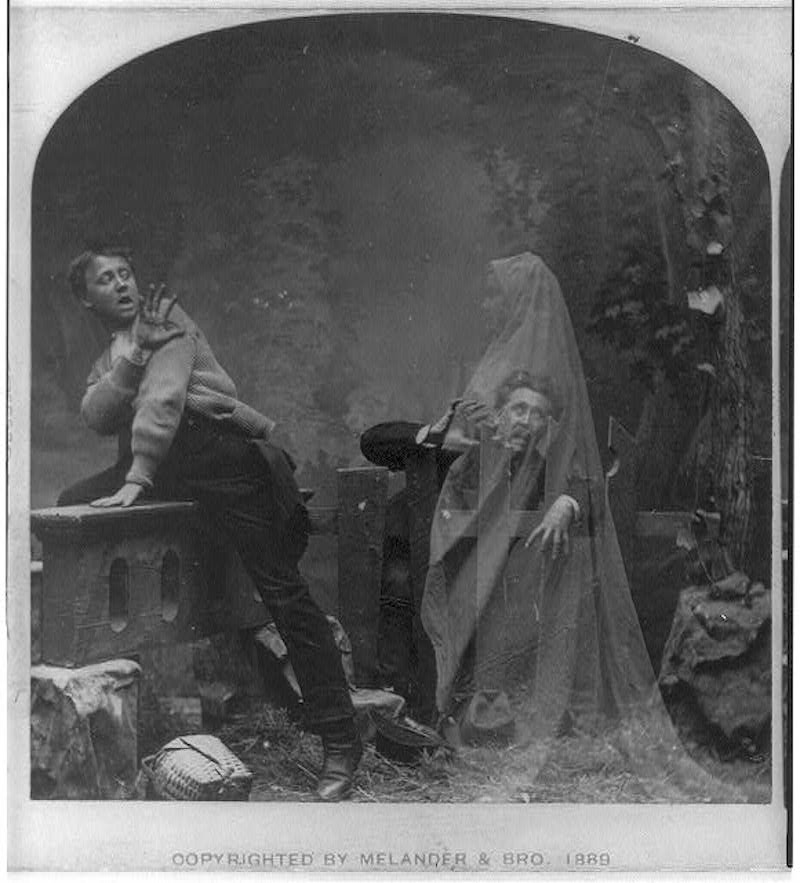

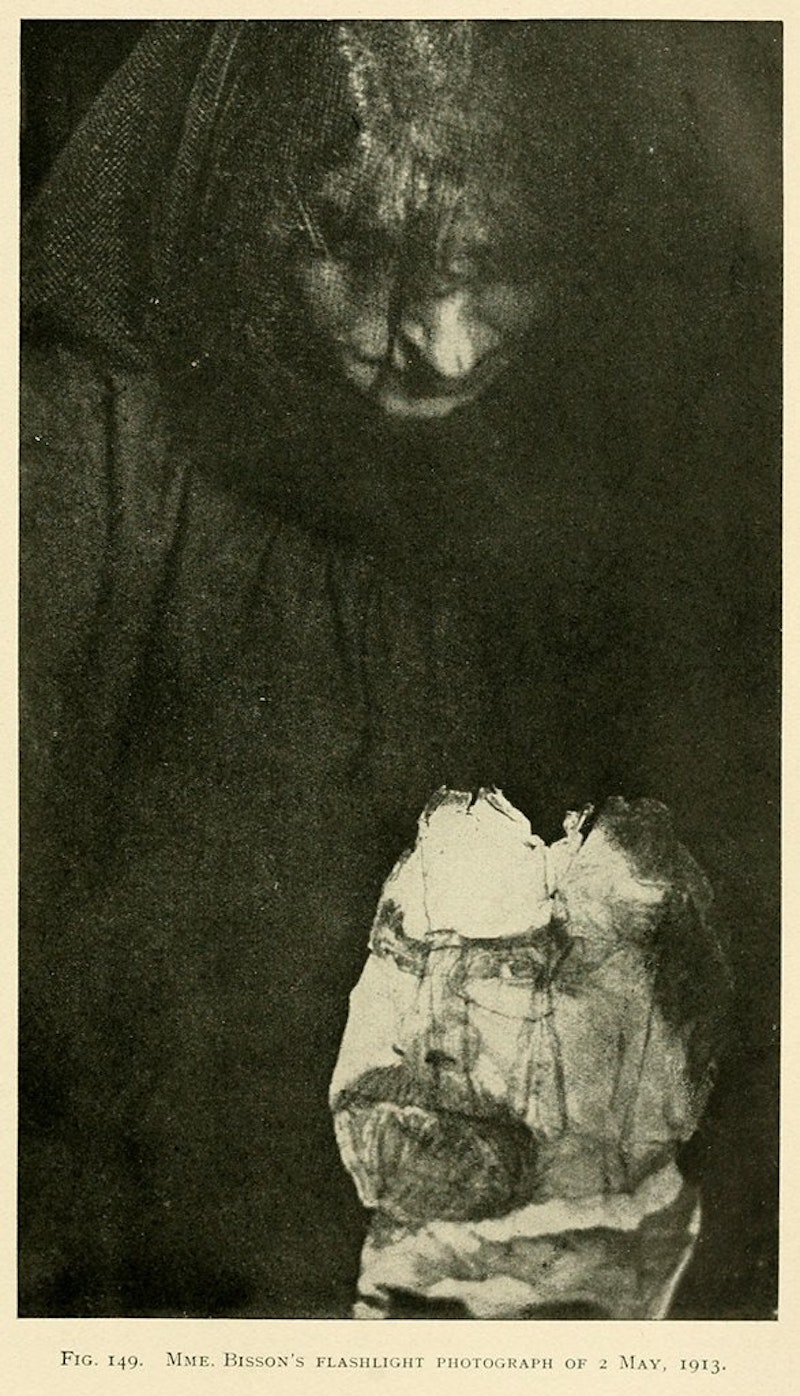

Untitled, ca. 1913, Photograph from Phenomena of Materialisation, Baron von Schrenck-Notzing

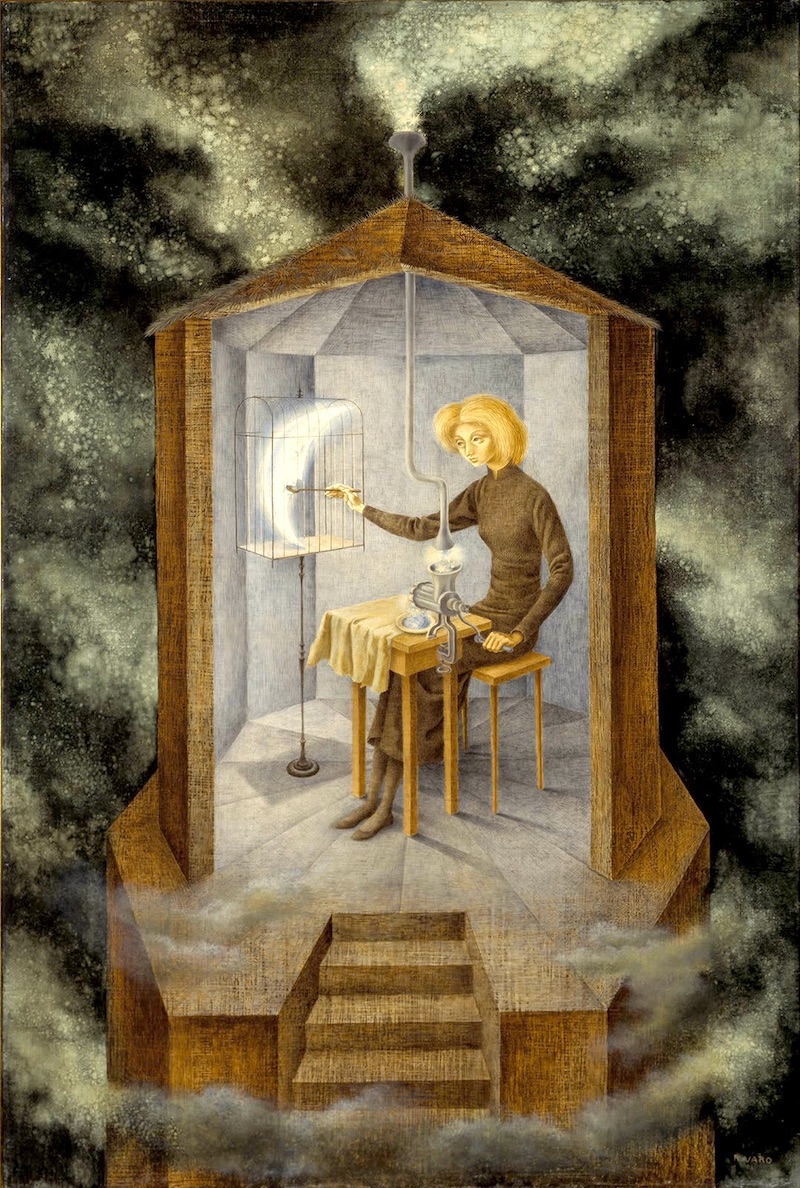

The Suffragists weren’t the only ones who took interest in Spiritualists’ techniques in communing with the dead. Throughout his career Andre Breton strongly objected to the notion of communing with the dead through automatic techniques, but he did believe in the creative outcomes by utilizing these automatic techniques. Breton and his contemporaries worked to strip automatism of both its clinical and spiritual frameworks, using it purely as a tool for creative practice. On the contrary, often eluded by Breton, artists like Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo had fully embraced spirituality in order to cope with the traumas that came from the World Wars and suppression from their male contemporaries. In Waking the Witch, Pam Grossman examines how these artists were greatly influenced by mythology, alchemy, and the occult in both their art, and also in their personal lives and friendship with one another.

Like Carrington and Varo had utilized, in contemporary Fourth Wave Feminism (specifically in the West/United States), people of all gender identities are now reclaiming witchcraft as a means of empowerment and liberation in retaliation of suppressive socio-economic practices. Both contemporary writers, and notable witches, Pam Grossman and Kristen Sollée explore this theme of reclamation in witchcraft and the occult through the subject’s ever changing connotations throughout history, and also in media culture today. Similarly, the way Spiritualism aided Victorian women during the tight social grasp of the era is still a potential for artists working today, who use this medium to grapple with and challenge related contemporary experiences and emotions. Shannon Taggart is a contemporary photographer whose work deals extensively with Spiritualism. She has said, similarly to other theoreticians of photography, that the interconnectedness of death and photography is inevitable since, “Photographs stop time by capturing a person’s disembodied presence and preserving them indefinitely”[4] Shannon Taggart, “Introduction: Spiritualism, Photography, and the Search for Ectoplasm,” Séance, ed. by Shannon Taggart (New York: Fulgar Press, 2019), 41-48.. She also adds Spiritualism into this mix because like photography, it also works to “transcend death” by evoking the deceased. As Spiritualists blurred the lines between science, spirituality, and gender politics, Taggart is working along those same lines today. She has stated that her work is in no way about trying to prove the validity of Spiritualists or the existence of the afterlife, but is rather a series of images that “evoke a union of past & present.” Taggart’s project originally sought out to explore the nineteenth-century Spiritualist community in upstate New York, Lily Dale. She pursued this series after learning about the death of a family member that a Spiritualist medium rightfully conveyed. Taggart’s images capture the unique spaces and silent power that a Spiritualist medium inhibits. Similar to the Suffragists, she is attracted to Spiritualism’s ability to generate a voice for an unheard or repressed point of view. By experiencing the effects that both this Spiritualist and grief had on her own family, she was inspired to explore this connection further.

Remedios Varo, Papilla estelar, ca. 1958, oil on canvas. Fuente: https://historia-arte.com/obras/papilla-estelar.

Spiritualism was used as a tactic by Victorian women as a form of expression and an emotional outlet for grief in a society that strictly regulated their behavior through rules of etiquette. Their techniques would later be channeled into strictly creative tools by Surrealists, as opposed to Carrington and Varo who had fully embraced the occult connotations in their own work and used it as channels for empowerment of feminine spheres. Spiritualism and magic continue to be a source of empowerment for marginalized peoples in Fourth Wave Feminism, a reclamation of one’s voice and serving as an outlet for reflection of one’s mortality when confronted by socio-political suppressions.

(Imagen destacada: The Haunted Lane, ca. 1889, fotografía)

| ↑1 | The Milk of Dreams, Cecilia Alemani, 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy. https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/statement-cecilia-alemani. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Barbara Goldsmith, Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1998), 48. |

| ↑3 | Anne Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), 2-3. |

| ↑4 | Shannon Taggart, “Introduction: Spiritualism, Photography, and the Search for Ectoplasm,” Séance, ed. by Shannon Taggart (New York: Fulgar Press, 2019), 41-48. |

Alexa Jade Frankelis is a researcher and visual artist based in New York City. She has recently received her BA in Art History and Criticism (Hons.) from Stony Brook University, and previously attended the BFA Photography and Video program at the School of Visual Arts. To further her passion for research, she is currently pursuing a MS degree in Library and Information Science at The Pratt Institute’s School of Information. As a researcher, Alexa has presented and published her papers and images about witchcraft, spirit photography, and other occult subjects in Blurden Zine, Crisis and Catharsis, and Stephen Romano Gallery’s exhibition, Apparitions. Her main focuses are mysticism and the occult within 19th to mid-20th century visual culture and theory. Instagram: @TheMourningMoon. https://linktr.ee/themourningmoon

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)