Search

To search for an exact match, type the word or phrase you want in quotation marks.

A*DESK has been offering since 2002 contents about criticism and contemporary art. A*DESK has become consolidated thanks to all those who have believed in the project, all those who have followed us, debating, participating and collaborating. Many people have collaborated with A*DESK, and continue to do so. Their efforts, knowledge and belief in the project are what make it grow internationally. At A*DESK we have also generated work for over one hundred professionals in culture, from small collaborations with reviews and classes, to more prolonged and intense collaborations.

At A*DESK we believe in the need for free and universal access to culture and knowledge. We want to carry on being independent, remaining open to more ideas and opinions. If you believe in A*DESK, we need your backing to be able to continue. You can now participate in the project by supporting it. You can choose how much you want to contribute to the project.

You can decide how much you want to bring to the project.

During the decades of the seventies and the eighties, after the death of Franco and during the first years of the so-called Transition, various activist groups produced an important quantity of graphic material. Posters, stickers, pins and leaflets are found stored in the headquarters of these groups, or are being compiled into archives that bear the weight of “political” and “activist” curatorial investigations and practices.

Posters like the ones we see here, or at least realised according to similar parameters and aims, were produced in the heat of autonomous movements that identified in graphics and its aesthetic possibilities a potent tool for questioning and ideological transmission. Conscious of the value of images and signs, they captured their ideas and vindications on paper or in actions on the street, that we are now moved to call performances.

This production, it’s worth remembering, was at the service of a political ideology and subject to processes of production that had little or nothing to do with the ones that prevailed in the art scene at that time. And as aesthetics is never neutral or ahistorical, the result, in some cases, was an iconographical and stylistic shake up that was nothing more than the reflection of a political desire to de-standardise and differentiate. It is the case of the graphics of the feminist movement, the evolution of which evidences an endeavour to break with the tradition of “good” design, at the same time the fruit of an aspiration for change, for amateurism and anonymity that characterised a large part of what was produced. The immense majority of documents aren´t signed and remain unattributed, due to the fact that they are inscribed within collaborative practices in which militancy and collectivity annulled all attempts at individual authorship. The primacy of do it yourself was complemented with the collaboration of artists, designers or fine art students who, relating to the feminist cause, contributed to it with their work.

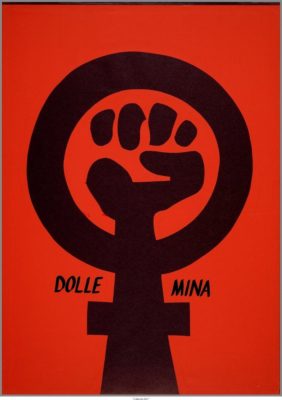

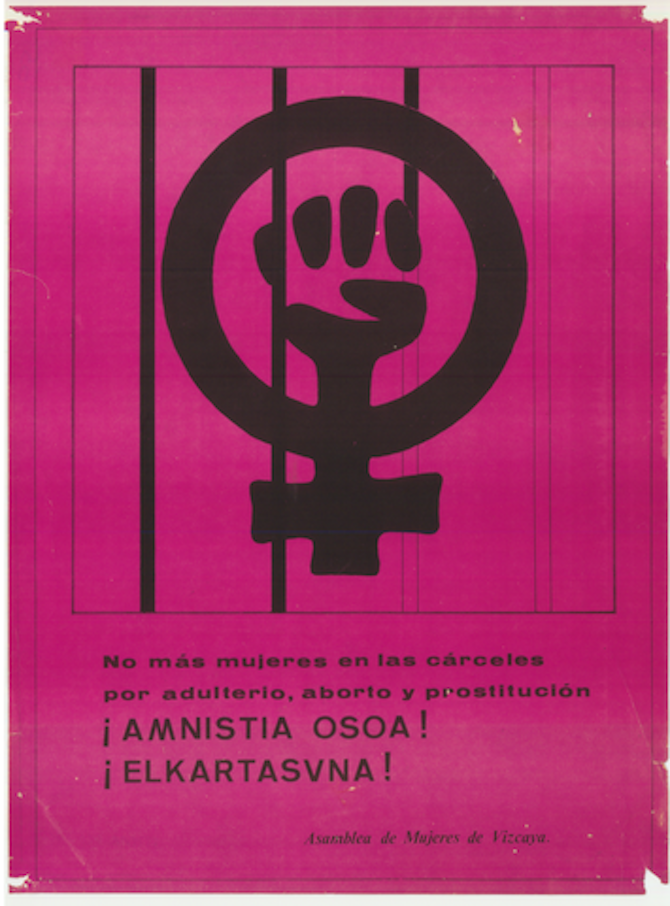

The posters and stickers are, on the whole, not dated, so stylistic criteria become a basic tool for dating. The evolution is fairly clear: the economy of forms and schematization that predominate in the decade of the seventies give way to a greater proliferation of elements, and a distancing from stylisation, in pursuit of more direct figurative proposals, from collage and photo-collage, to typographical contaminations…What is maintained are the chromatic preferences (pinks, purples…) the representation of the female body (although the forms change) and the constant presence of the feminist symbol.

The type of graphics is not so different from that proposed by other contemporary groups in Europe and the United States; coincidences are frequent. However surprising it might seem, given the generalised delay the consequence of the dictatorship, the incipient feminist movement across the country had aspirations and modus operandi that could be described as international.

The demands centred, as in other countries, on the question of sexual and reproductive rights, though here it had to face up to an ultraconservative legislation that had barely changed since the death of the dictator. A poster signed by the Asamblea de Mujeres de Vizcaya (Vizcayan Women’s Assembly) demanded amnesty for the 350 women who in 1976 remained imprisoned for the so-called “specific crimes” (adultery, abortion and prostitution). In one of the first posters of the Basque feminist movement, the prison bars don’t quite take form, alluding perhaps to a potential amnesty. Imprisoned, the feminist symbol uses the variant of the raised fist, typical of the movement in those years, accounting for the close relations between feminism and the struggles of the radical left. The same icon appears in a poster from that time made by the socialist feminist groups Dolle Mina, very active in Belgium and the Netherlands from the end of the seventies. The Dolle Mina, who took their name from the activist of the first wave, Wilhelmina Drucker (1847-1925), focused their struggles on questions such as abortion or access to methods of contraception, through surprising street actions and an impressive graphic production.

I imagine thirty years ago, here, the street was something of an exhibition space. The walls contained forms, images, messages…Over time they have alluded to aesthetic motives for prohibiting the posting of posters, that today, when it is the case, can be contemplated in museums and art centres, cohabiting with the institutionalisation of everything that has for a while now been destroying us.

Maite Garbayo is a writer and researcher. Art history, feminist crticial theory and pyschoanalysis are a few of the tools of her trade. She combines her research and writing with periods of teaching. Currently, she is working on her doctoral thesis and is the editor of the magazine {Pipa}.

"A desk is a dangerous place from which to watch the world" (John Le Carré)